How America Got Stuck With Two Parties

The messy, improvisational birth of Democrats and Republicans — and why their identities keep shifting

Americans love to complain about political parties.

So did the Founders.

In fact, they straight up feared them. Alexander Hamilton not so subtly referred to political parties — or “factions” in Founder-speak — as government’s “most fatal disease.”

In his 1796 Farewell Address, President George Washington warned against the “baneful effects of the spirit of party,” fearing that rival factions would place loyalty to team above loyalty to nation (sound familiar, anyone?). His warning was sincere and yet already obsolete at the time it was issued. While Washington spoke, his own administration had already split into two competing camps, led by his treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, and his secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson.

Despite their worries, the Founders knew political parties were inevitable. James Madison warned that factions were “sown into the nature of man,” a force that had appeared in every popular government throughout history. Whether for safety or political ends, humans organize around shared interests. When folks disagree about interests, they compete for power to pursue their preferred outcomes. That competition produces sides. And almost immediately, sides become parties.

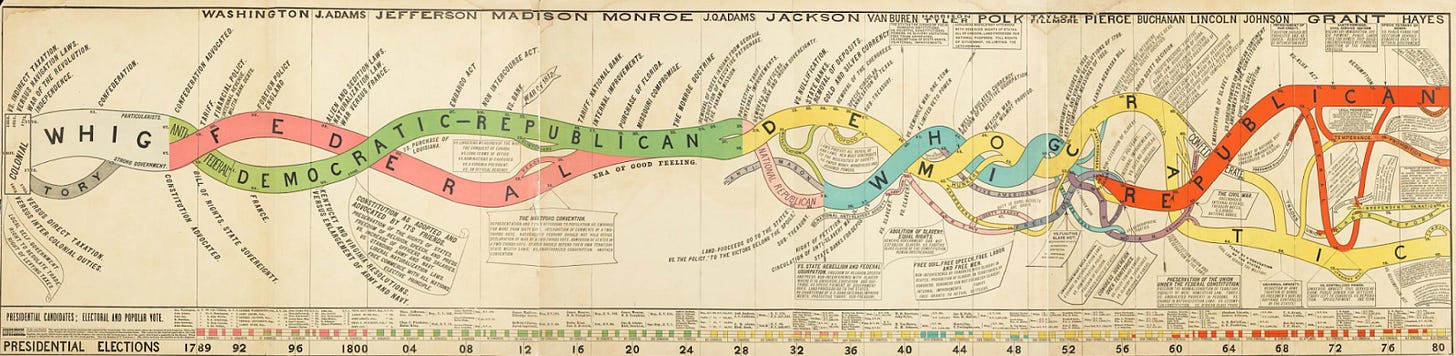

But what might surprise us today is just how fluid those parties have been throughout our history. Far from fixed teams with timeless values, political parties in America have repeatedly reinvented themselves in response to new conflicts, changing coalitions, and evolving policy goals. Over 230 years, they have swapped constituencies, shifted ideological priorities, and traded regional strongholds — often more than once.

Today, Americans casually say “Democrat” and “Republican” as if those labels had always meant what they mean now. The names have largely remained the same; what they’ve stood for has not.

This is the story of how the United States went from having no political parties at all to having two powerful, deeply polarized organizations that shape nearly every part of American life.

When Parties Weren’t Supposed to Exist

The Constitution says nothing about political parties. Not a word. Many Framers hoped against hope that their ingenious design of a federalist republic with layers of checks and balances would produce a government of dispassionate statesmen who would deliberate toward the common good.

Instead, within a few years of the Constitution’s ratification, the nation found itself divided between Hamilton’s Federalists, who favored a strong national government with commercial and financial infrastructure, and Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans, who wanted a more agrarian, decentralized, state-centered republic.

These weren’t parties in the modern sense. They weren’t raising gobsmaking amounts of campaign funds or overseeing an extensive campaign machinery. But they did behave like two rival movements working toward rival political ends. This style of ideological conflict quickly became the default mode of politics.

As popular governments have learned throughout time, parties made governing possible. Coalitions united in shared goals could organize legislative agendas, marshal votes, and hold opponents accountable. Without them, government would splinter into competing interests, with no reliable way to build majorities or act. The Founders feared parties would divide the country; instead, parties became the system’s skeleton, the basic structure that allowed it to work. And once created, they proved impossible to get rid of.

Parties Change When the Country Changes

The parties of Jefferson and Hamilton largely dissolved after the War of 1812, but the underlying impulse — to organize around big national arguments — persisted. The Democratic Party that emerged under Andrew Jackson was not a continuation of Jefferson’s world so much as a new coalition born of new circumstances: westward expansion, mass participation in government, and resentment of centralized power.

Over the next two centuries, the parties repeatedly reorganized themselves around the biggest conflicts of their times.

Four major movements stand out:

The fight over slavery

The industrial revolution and the New Deal

The civil-rights movement

Globalization and identity politics

Each moment split the country. Each time, the parties adapted — or were replaced.

The result is an American two-party system that looks continuous on the surface yet is constantly reinventing itself underneath.

Slavery Rewrites the Map

By the 1850s, one issue towered above all others: whether slavery would expand westward into new American territory. The existing party system simply couldn’t contain the conflict. The Whig Party — one of the two dominant national parties for a generation — fractured under the strain and collapsed.

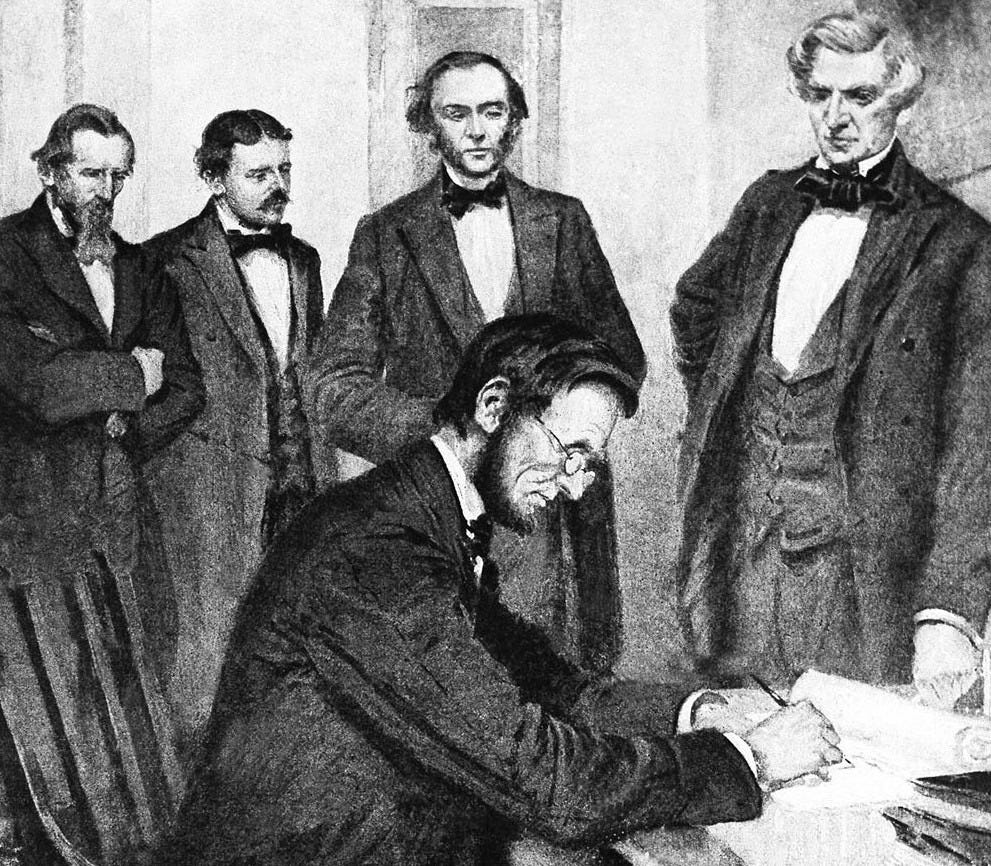

Abraham Lincoln was part of that unraveling. Fourteen years before becoming president, Lincoln was a one-term congressman elected on the Whig ticket, representing a party that could no longer hold together once slavery’s expansion became the defining political question.

As the Whigs splintered, a tangle of smaller political parties scrambled for relevance. Short-lived movements like the Free Soil Party, the Know-Nothings (American Party), the Liberty Party, and various state-based anti-slavery coalitions each tried to stake out territory. But none was strong enough to win enough elections to realize its political goals. Leaders soon recognized that if they hoped to stop slavery’s expansion, they needed to fuse their efforts under a single political banner with national reach.

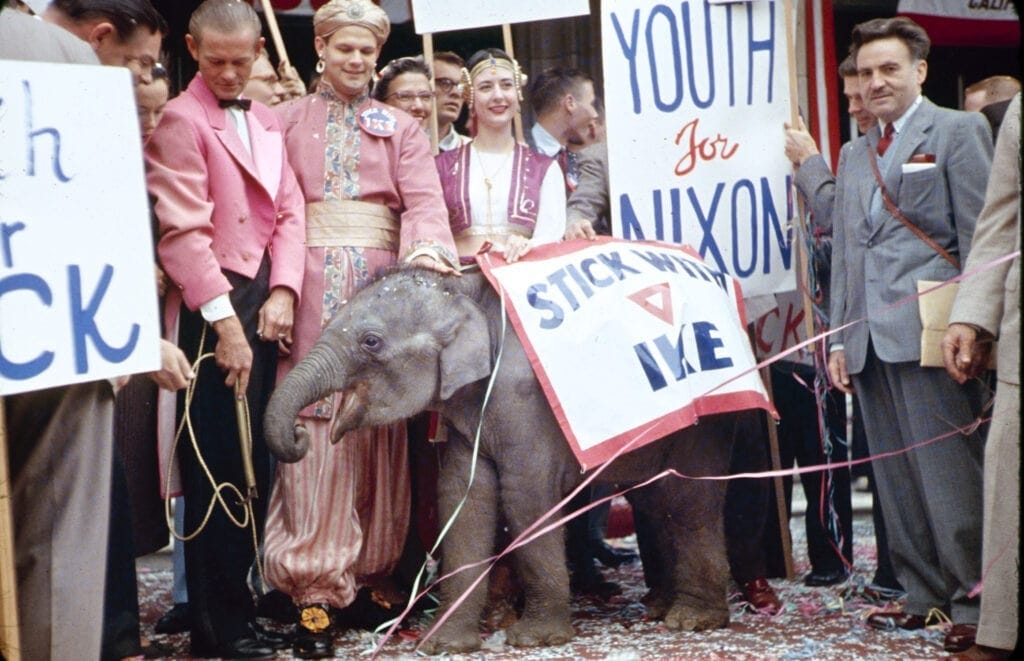

That banner became the Republican Party, founded in 1854 as a coalition of anti-slavery Whigs, Free Soilers, abolitionists, and disaffected Northern Democrats. Its mission was clear: halt the spread of slavery into new states. Just six years later, in 1860, this new party won the presidency after choosing Abraham Lincoln as its standard-bearer.

With that victory, the partisan map flipped. Republicans became the party of Northern industry and anti-slavery sentiment; Democrats consolidated in the South, defending slavery and later white supremacy.

It was the first great party realignment in American history — a moment when the entire party system re-sorted around the defining moral and political issue of the age.

It would not be the last.

Industrialization and the Rise of Big Government

The Civil War ended slavery, but it did not settle the political order.

During Reconstruction (1865–1877), the Republican Party dominated national politics as the party of Union victory and emancipation. It championed civil rights protections, passed the Reconstructionist 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, and built support among newly enfranchised Black voters in the South. Democrats, meanwhile, became the party of Southern white resistance, violently reasserting control through Jim Crow laws once federal troops withdrew in 1877.

As Reconstruction faded, the issues animating American politics shifted again. The Gilded Age brought runaway industrialization: vast fortunes, powerful monopolies, brutal working conditions, and widening income inequality. Republicans generally aligned with big business and industrial expansion. Democrats were split, with some courting agrarian and labor interests, others siding with conservative economics.

By the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s), both parties were feeling the pressure of reform movements. Smaller third-party forces — the Populists, Prohibitionists, Socialists — pushed ideas like railroad regulation, trust-busting, banking reform, and women’s suffrage. Many of their demands eventually found homes in the major parties as they once again absorbed outside energy to preserve their viability. It was another reminder that, in American politics, parties evolve to survive.

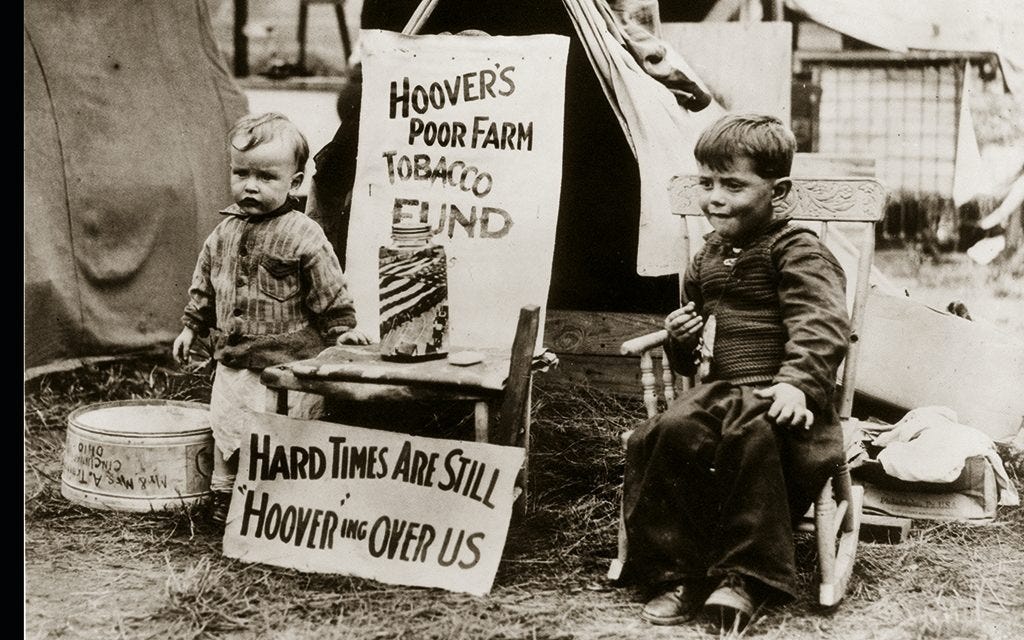

Then came the Great Depression, and with it the most dramatic realignment since the Civil War.

In the 1930s, economic collapse forced a national reckoning. President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal infused government into nearly every corner of the economy — unemployment insurance, Social Security, labor protections, banking regulation, infrastructure jobs. To pass this sweeping agenda, the Democratic Roosevelt stitched together one of the most durable coalitions in U.S. history: Northern workers, labor unions, new immigrants, Black Americans in Northern cities, and Southern whites (who used to be reliably Republican).

This New Deal coalition made Democrats the dominant national party for a generation and cemented a new ideological expectation that we now find familiar: Democrats favored a bigger, more active federal government.

Republicans opposed much of this expansion rhetorically, but even they eventually accepted the basic architecture of the welfare state. Still, ideology was not yet neatly sorted. The country had liberal Republicans (especially in the Northeast) and conservative Democrats (especially in the South).

In this era, the parties were coalitions of convenience, not ideological purity.

That would change. Dramatically.

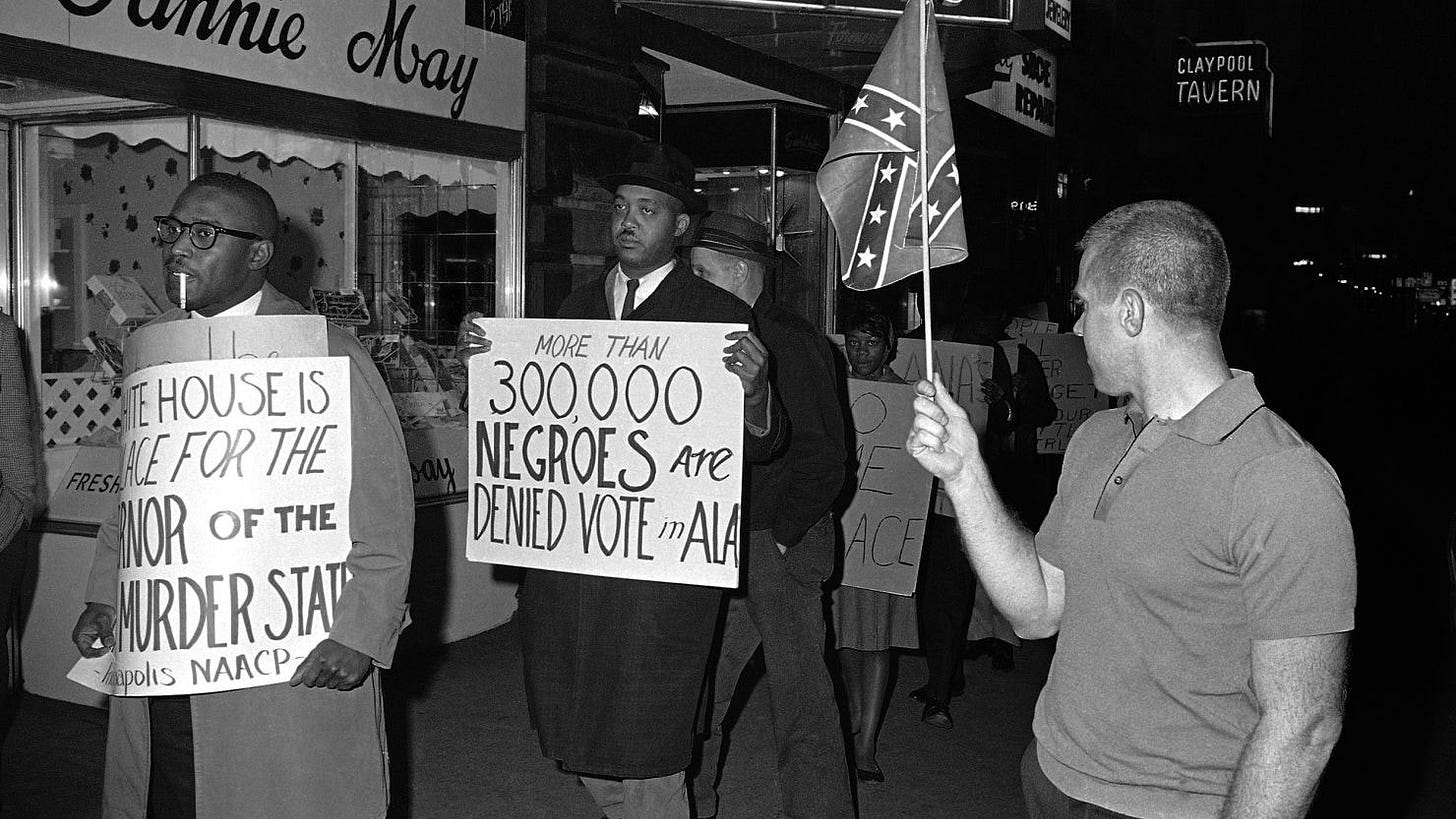

Civil Rights Splits the Parties

The New Deal coalition began to unravel in the 1960s. When Democratic leaders, including Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, pushed for sweeping civil-rights legislation, many white Southern Democrats revolted. White Southern Democrats, long the backbone of the party, broke away in defiance of federal desegregation orders and voting-rights enforcement. Many rallied under the banner of the “Dixiecrats,” a segregationist faction led by South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond that embodied the South’s backlash to civil rights.

Meanwhile, newly enfranchised Black voters — empowered by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — overwhelmingly supported the candidates and party that defended their rights: the Democrats. For the first time since Reconstruction, Black Americans became a decisive national voting bloc.

Over the next two decades, the parties reshuffled their constituencies. Democrats became increasingly urban, multiracial, and socially liberal. Republicans became increasingly suburban and Southern, appealing to white voters alienated by civil-rights reforms and cultural change. Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” formalized this shift, seeking to attract disaffected white Southerners through a rhetoric of “states’ rights” and “law and order.”

This was the second major realignment. Federal power, once the enemy of Southern Democrats, was embraced by liberals for social reform. And Republicans, once the party of Lincoln, emancipation, and the end of slavery, became home to many white Southerners who supported and defended Jim Crow policies.

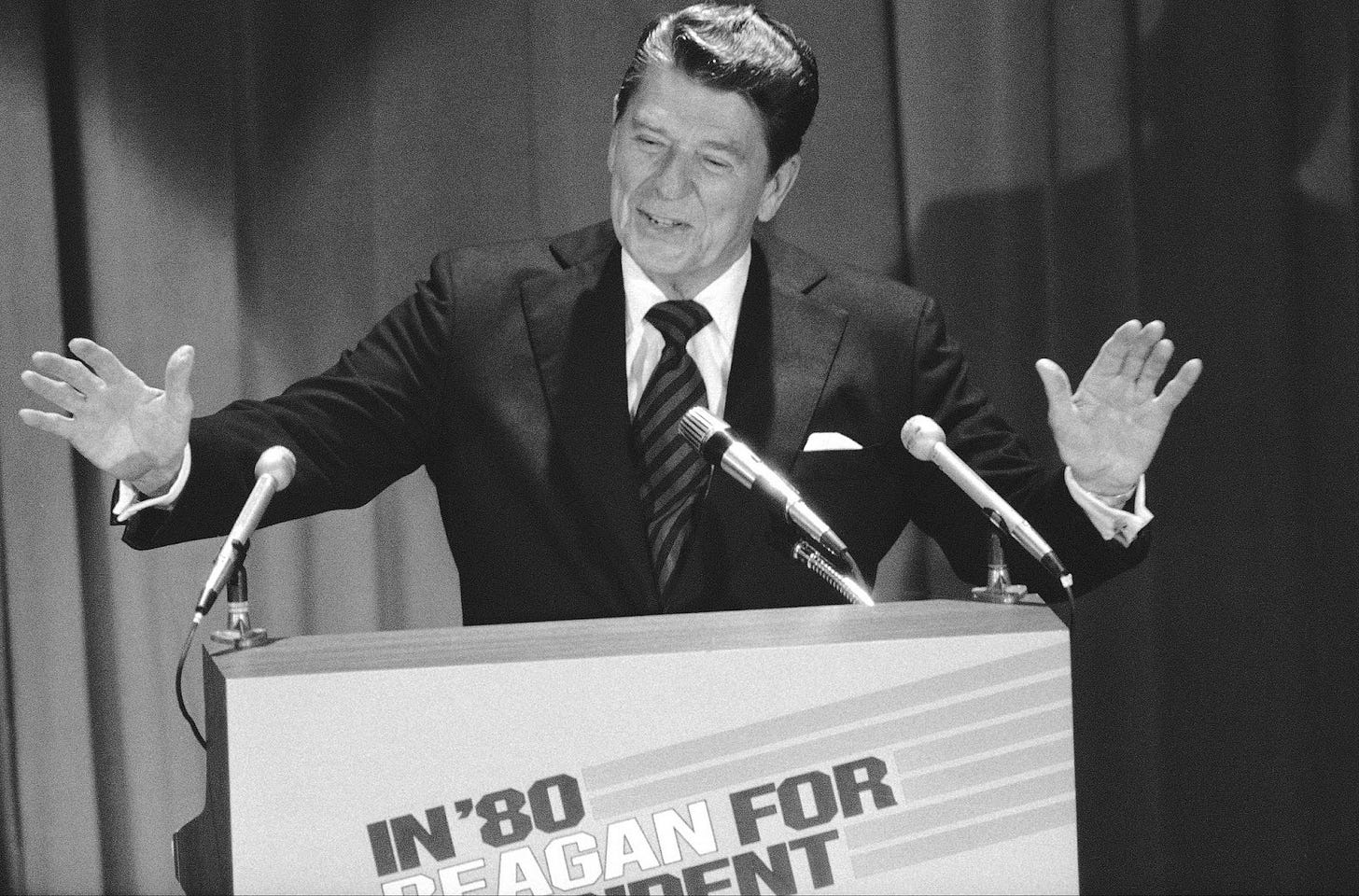

By the late 1970s, new forces were reshaping politics again. The social upheaval of the 1960s, Watergate, the economic stagnation and inflation of the 1970s, and Cold War anxieties fostered a public backlash against perceived government overreach.

And by the 1980s, Ronald Reagan united business interests, anticommunist hawks, and religious evangelicals into a modern conservative coalition. The Republican Party became the champion of limited government, low taxes, and traditional values, while Democrats increasingly defined themselves as the party of social protections and inclusion. The resulting “Reagan Revolution” eventually gained the GOP Republican congressional majorities for the first time in decades.

For a moment, the story seemed straightforward.

Then the coalition changed yet again.

The Obama Decade — and the Shock That Followed

Barack Obama’s election in 2008 brought together an emerging Democratic coalition of younger voters, racial minorities, urban residents, and college-educated suburbanites. Democrats increasingly reflected the population of growing metropolitan areas — diverse, secular, and professional.

At the same time, many working-class white voters, especially those without college degrees, began drifting away from the party. Globalization, deindustrialization, and cultural change left them feeling overlooked. Democrats increasingly became the party of cities; Republicans became the party of smaller towns and rural regions.

Then came Donald Trump.

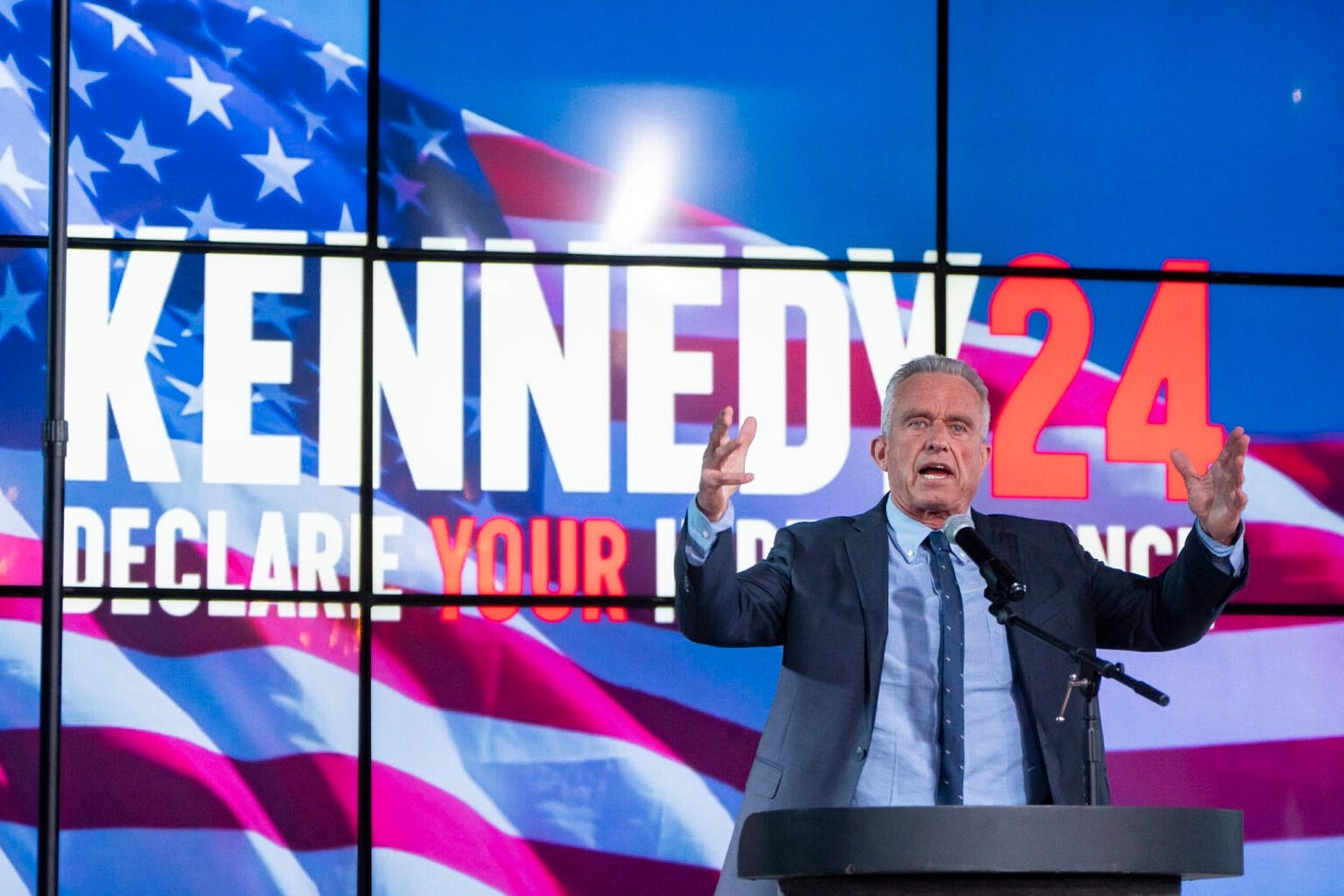

Trump was no traditional conservative. He denounced bipartisan free trade agreements, imposed tariffs, vowed to protect Social Security, and attacked US military entanglements overseas — upending the “Bush Doctrine,” the post-9/11 foreign policy that emphasized spreading democracy abroad and maintaining a robust US presence in global affairs.

Trump’s populist “America First” platform centered on culture, identity, and immigration as defining political questions. His messaging was a sharp break from the relatively tolerant, pro-immigration stance of earlier Republican leaders like Ronald Reagan, who famously described America as a “shining city upon a hill,” and George W. Bush, who supported pathways to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.

Trump’s message, however, resonated with voters who felt economically squeezed and culturally alienated. And as a result, the modern GOP moved away from Reagan’s “fusionism” — the ideological blend of free markets, moral traditionalism, and hawkish foreign policy — and toward a populist nationalism skeptical of globalism, hostile to immigration, and organized around cultural grievance.

In his own unconventional way, Trump has remade the Republican coalition as dramatically as Lincoln or Reagan. Republicans became more working-class, less college-educated, more rural, more white, and more religious. Democrats, meanwhile, grew more college-educated, suburban, urban, and multiracial.

These shifts didn’t just change what each party stood for — they changed what each party was. As coalitions hardened along cultural, racial, educational, and geographic lines, partisanship became less about policy and more about identity. As identities stack — religion, race, geography, culture — partisanship becomes a mega-identity, blurring the line between political disagreement and personal worth.

As a result, the parties stopped being defined by what you believe and increasingly were defined by who you are. Put simply, in the identity-politics era party isn’t policy; party is tribe, and it has flipped how we decide whom to support. As political scientist Lilliana Mason and others have shown in experiment after experiment, we Americans like to think we choose candidates based on issues — but it usually works the other way around. We adjust our issue positions to match our team, contradictions be damned.

That helps explain how Trump has reshaped the GOP so quickly. Supporters didn’t merely tolerate his breaks from conservative orthodoxy — they absorbed them. When he reversed course on issues, many Republicans, including many GOP politicians with records bashing Trump and his positions, reversed with him without ever thinking twice. The identity-level commitment to the party reigned supreme.

Why We Still Have Only Two Parties

This brief history makes it clear that there has been a lot of churn in what the parties stand for. But despite all this, two parties — and only two — continue to dominate American politics.

That isn’t cultural preference or historical coincidence. It’s math.

In the US we run winner-take-all (or first-past-the-post) elections; only the top vote-getter wins the seat. Finishing second gets you nothing. As a result, backing a minor-party candidate who can’t win risks handing victory to the candidate you like least. Over time, voters learn to pick the viable option rather than “waste” a ballot on a party with no chance.

Political scientists have long recognized this dynamic. It even has a name: Duverger’s Law — the observation that winner-take-all systems almost inevitably produce two major parties because voters and politicians gravitate toward the coalitions that can actually win.

History bears this out.

Third-party movements occasionally flare — Populists in the 1890s, Progressives in 1912, Dixiecrats in 1948, Libertarians, Independents, and Greens more recently — but they rarely survive as independent forces. Instead, their ideas get absorbed. Industrial workers joined Democrats; antislavery activists joined Republicans; Southern segregationists eventually migrated to the GOP.

The result is a system where parties almost never disappear. Instead, they are captured, reshaped, and repurposed from within a broader party that wants a better chance at winning. So unless the United States completely changes its way of electing representatives, the two-party system is here to stay.

But within it, we see three key takeaways about how the parties change, sometimes dramatically.

First: Party labels are not fixed, and they are constantly evolving. Your great-grandparents’ Republican Party was the party of Lincoln and civil rights. Their Democratic Party was the party of the segregated South.

Second: Parties change because the country changes. Each generation forces a re-sorting: around slavery, around industrialization, around civil rights, around globalization.

Third: Movements rarely form new parties; they capture old ones. Abolitionists helped found the Republicans; civil-rights activists reshaped Democrats; populists transformed the GOP under Trump.

Why This History Matters

“Democrat” and “Republican” are labels with centuries of baggage — much of it contradictory. Understanding that the parties have repeatedly transformed helps clarify confusing realities today:

Why do some blue-collar workers vote Republican while suburban professionals vote Democratic?

Why did the party of Lincoln become the party of the South?

The answer to such complicated questions is frustratingly simple: because the coalitions keep changing. And they will continue to change as new industries emerge, migration reshapes communities, and the country renegotiates its deepest arguments over identity and power.

In the Founder’s utopia, political parties were never supposed to exist. And yet without them the system sputters. Parties organize voters, structure debate, and make governing imaginable. They are imperfect, frustrating, resilient — and indispensable.

Which means that as fixed as parties may feel year to year, the version we live with today is still evolving. Parties aren’t anchored to eternal ideologies — they are vessels for whatever coalitions demand of them at a given moment. They reflect us: what we fear, what we value, what we expect from government.

And that should be a source of power, not frustration. If we don’t feel seen or heard by our parties, we are free agents. Parties chase votes; they go where the people are. When coalitions shift, parties follow — because in a democracy, they have no choice.

What great write-up! My father always says that America cannot survive with more than two parties, I am not sure that is true, but history seems to support this. I know that this is not part of the discussion here, but I wonder how Ranked Choice Voting could lessen the extremes of each party, allowing more moderation to rise. Would love some thoughts on that.

When today's Republicans like to call themselves "the party of Lincoln"... they are gravely misinformed.