Has Your Election Already Been Won?

Most congressional districts are a lock for one party — and that's a problem

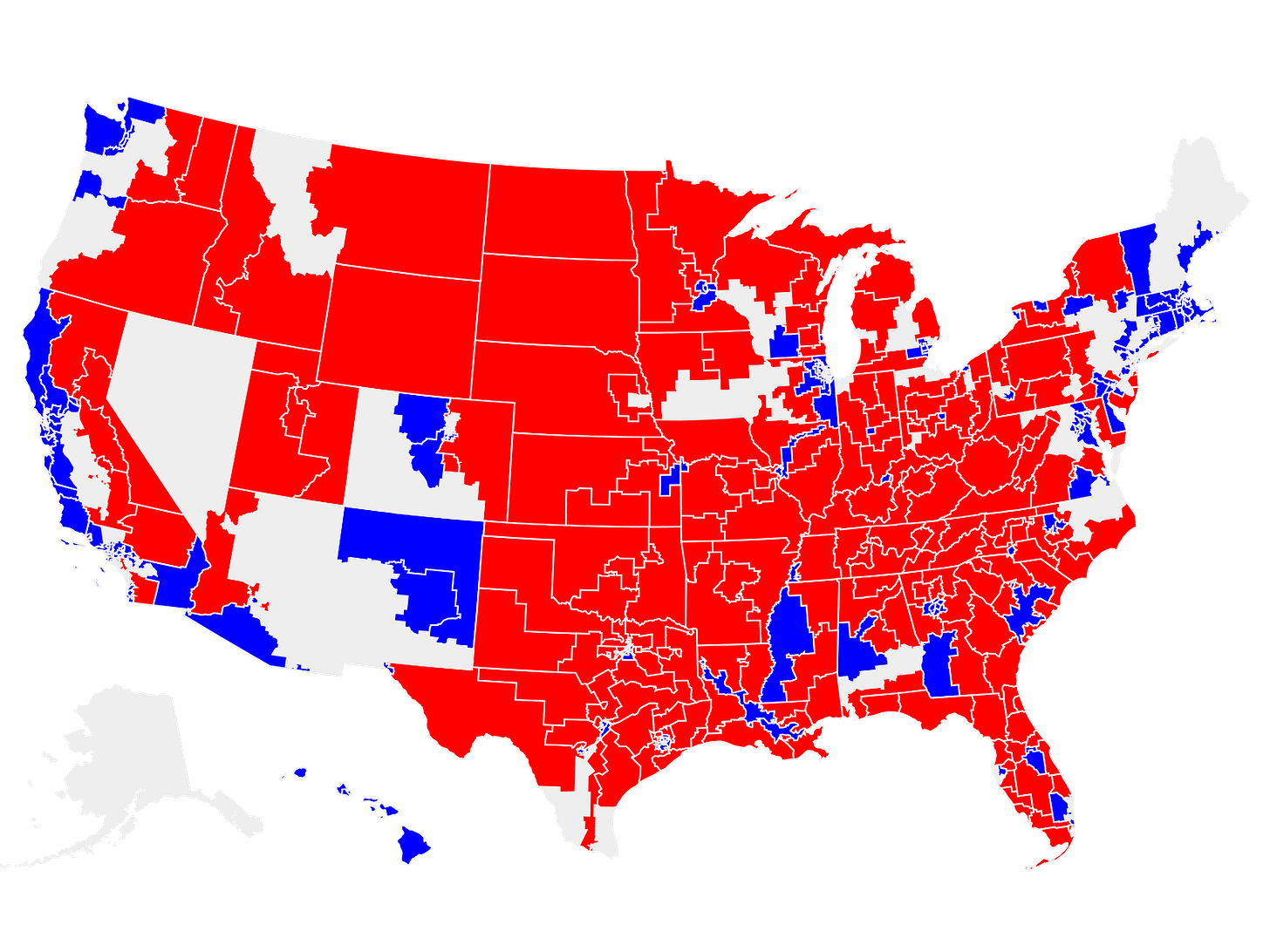

Before reading another word, take a look at the map below and try to guess what it shows.

A few things may jump out immediately. The outlines are the 435 House congressional districts used in the 2024 elections. The colors are familiar: red for Republicans, blue for Democrats.

And almost the entire map is filled in. You have no problem identifying every s…