From the Press Gallery: The State of the Union Is on Life Support

Inside the room where it happened—and why this tradition may not survive

Sitting in the House press gallery during President Trump’s primetime address on Tuesday night, there was a lot to think about.

What did his words mean for the future of Ukraine policy? Trade policy? Elon Musk’s efficiency initiative? How were lawmakers reacting in the room? How would Americans respond across the country?

And yet, as the speech wore on — it was the longest presidential address to Congress in modern history — my mind kept slipping to a different question: What would Thomas Jefferson have made of the spectacle playing out in front of me?

It’s always fun to imagine at modern political events what the Founding Fathers would be thinking of the country they helped build, and an ornate room like the House chamber makes it easier than most to envision men with powdered whigs seamlessly sidling in.

In this case, though, there wasn’t much to wonder about. Jefferson was on record hating the State of the Union address, so much so that he opted to deliver his in writing, rather than as an in-person speech like his predecessors George Washington and John Adams. (Tuesday night’s speech was not technically a State of the Union, since a new president’s first time addressing Congress isn’t given that designation, but there’s no functional difference. The exact same rituals accompany the address no matter what it’s called.)

Why exactly Jefferson decided to forgo an oral speech is a matter of dispute among historians. Although he was a famous writer, some have suggested that he did so because he was a tepid public speaker. Others have speculated that it was because of transportation issues: the president and Congress were no longer located as close to each other as they were under the first two presidents, and it wasn’t easy to traverse the swampy new capital in Washington, D.C.

The most popular explanation is that Jefferson thought the idea of the president lecturing lawmakers was too monarchial, a disturbing holdover from the “speech from the throne,” the annual event in which the King or Queen addresses the British Parliament.

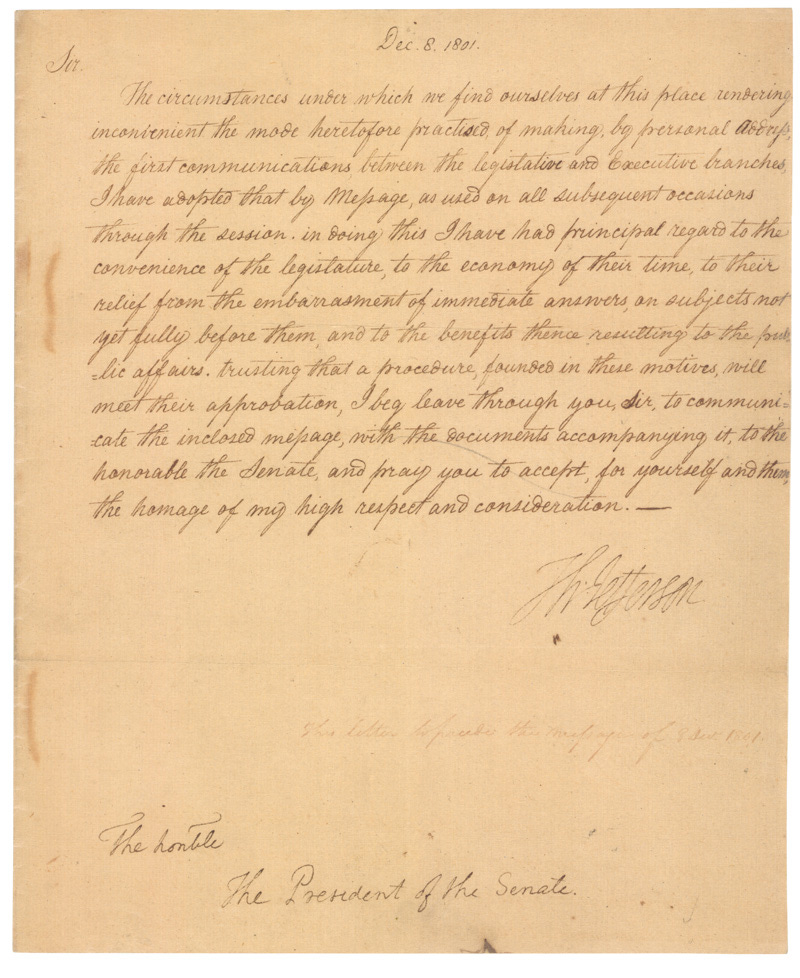

Jefferson actually wrote a note to Congress explaining himself, though, and if you read his own words, none of these potential answers come up. In deciding not to deliver his annual message orally, Jefferson wrote, “I have had principal regard to the convenience of the legislature, to the economy of their time, to their relief from the embarrassment of immediate answers on subjects not yet fully before them, and to the benefits thence resulting to the public affairs.” (The message and the explanation were both delivered to Congress by his assistant Meriwether Lewis, of “Lewis and Clark” fame.)

Jefferson, who had spent his vice presidency compiling a manual of Senate procedure, was a strong believer in the legislative process — which he thought should be deliberative, not knee-jerk. Under Washington and Adams, each chamber of Congress composed its own response to the annual addresses, even though they often had little information beyond what the president had given them.

The precedent set by Jefferson would last more than 100 years, as presidents continued to write, instead of speak, their State of the Union messages. The pattern was broken by Woodrow Wilson in 1913, who opted to stand before Congress and deliver his statement orally — a tradition that continued ever since.

Which brings us to Tuesday night, where “immediate answers” from lawmakers abounded, including quite a few commemorations of “the triumph of party.” (As Trump spoke to Congress for an hour and 40 minutes, the “economy of their time” didn’t seem to be much of a consideration.) If Jefferson had been sitting next to me in the press gallery Tuesday — where I couldn’t see the president, but had an excellent view of the congressional reactions — I can’t imagine he’d have been pleased.

Unlike under Washington and Adams, when the House would sit on one side when the president spoke and the Senate would sit on the other, modern State of the Union audiences are divided into parties: Democrats from both chambers crowd into the left side of the aisle, Republicans congregate on the right. (Those seating arrangements are an export from the French Revolution.)

Staring down at the right side was like watching a rollicking campaign rally. Republican lawmakers cheered, whistled, pumped their fists. They chanted “U-S-A” and finished the president’s slogans for him: “Drill baby drill,” “Made in America.” When Elon Musk was mentioned, they applauded and pointed at him happily. (He was in the House chamber, sitting just a few galleries away from me.) Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) wore a red hat that said, “Trump Was Right About Everything”; at one point, Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC) stuck a mini American flag in his lapel.

As Trump listed off idiosyncratic government spending identified by Musk, the GOP members roared in laughter at each one. From my vantage point in the gallery, I could see House Majority Leader Steve Scalise (R-LA) banging his fist on the table in front of him, in what seemed like somewhat of an overly forced performance.

Then, I’d turn my head to the members on the left side, who seemed to be sitting in an entirely different universe. For much of the speech, a silent protest played out, with irate-looking Democratic lawmakers holding up small black paddles reading “FALSE” whenever Trump made an untrue claim. (He made at least 26, according to the Washington Post.)

At other points, though, the protest wasn’t so quiet. Early in the speech, Rep. Al Green (D-TX) stood up to quibble with Trump’s boasts about the “mandate” that he won in November’s election. “You have no mandate to cut Medicaid!” he shouted, shaking his cane at the president.

House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) repeatedly told Green to sit back down; when the Texas Democrat refused, Johnson ordered House officials to remove him from the chamber. As Green exited, Republican lawmakers sang out: “Nah, nah, nah, nah, goodbye!”

No other Democrats were forced out of the room, though others yelled out brief provocations, from “Bullshit” to “January 6th.” A steady stream of Democrats voluntarily followed Green out the door at certain points, including Rep. Jasmine Crockett (D-TX), who defiantly stood with her back to the president for several moments before leaving.

Even Jefferson, with his insistence that the president not be treated like a king, would have been horrified by the Democratic disrespect on display — and, as a believer in the dignity of Congress, by the Republican taunts that followed.

Throughout the speech, as Jefferson feared, Democrats and Republicans alike responded to Trump’s words with almost robotic displays of disgust or support, respectively, without any consideration of what the president was actually saying.

As I’ve written here previously, a fair amount of bipartisanship actually takes place under the surface at Capitol Hill — but all of it went out the window Tuesday night. When Trump mentioned the TAKE IT DOWN Act, a bipartisan bill criminalizing the posting of non-consensual intimate imagery online, no Democrats stood to applaud, even though it passed the Senate unanimously just last month.

When the president called on Congress to “get rid of the CHIPS Act,” Republican lawmakers leapt to their feet, even though many of them supported the bipartisan legislation (an effort to increase domestic semiconductor manufacturing) during the Biden era.

I watched Republicans applaud things I know they do not support, and Democrats stay seated as Trump mentioned things they do. Some cracks were evident — but only some. As Trump championed his freeze on foreign aid and federal hiring, Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV) — who has criticized aspects of his spending decisions — stayed seated for several noticeable moments, but eventually joined her colleagues in applause. Several Russia hawks also seemed to hesitate to applaud Trump’s statement that Moscow is “ready for peace” in Ukraine; they, too, gave in.

Meanwhile, when the president introduced the family of Corey Comperatore, the firefighter who was killed during the attempt on Trump’s life last year, Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) was the only Democrat who I saw stand. As Trump mentioned a 13-year-old who’d battled cancer, a high school senior newly admitted to West Point, and relatives of Americans killed by undocumented immigrants, Democrats remained planted in their seats.

None of this is new, per se, but it is an escalation. State of the Union addresses have been growing rowdier for years: the first known disruption was in 1975, when several Democratic lawmakers silently walked out of Gerald Ford’s address. Another notable development came in 2009, when Rep. Joe Wilson (R-SD) shouted “You lie!” at Barack Obama. Both of these relatively mild actions — which would barely have caught notice last night — shocked Washington in their respective eras; the House passed a resolution rebuking Wilson, who later apologized.

Things got worse under the last two presidencies, as then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) ripped up the pages of Trump’s speech in 2020, and House conservatives took to routinely heckling Joe Biden during his addresses.

But no presidential speech to Congress has gone quite like the one on Tuesday night, which was the first time a lawmaker was ejected from such an address and the first time large swaths of lawmakers held up signs in protest (including Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-MI), who used a whiteboard to continually write out new messages of disapproval during the address). Democratic leaders also declined to escort Trump into the chamber, a bipartisan ritual that survived the first Trump and Biden eras.

And, in the past, although most ovations are typically from the president’s party, there have usually been at least some applause lines shared across party lines.

Where lawmakers once organized themselves by chamber in how they sat and responded to the addresses, they are now allegiant to party first and then to institution, following their faction even when it undercuts their own principles (or their own power). When Trump mocked Biden’s insistence that new legislation was needed to secure the border (“all we really needed was a new president”), Republican lawmakers chanted “Trump! Trump! Trump!” There was no way they could have more viscerally aligned themselves behind an executive, even as he was scoffing at legislative power. The separation between the branches has now collapsed; party reigns supreme.

For Jefferson, who viewed Congress as the primary vehicle of public policy — the “director,” not the “instrument,” of the executive, as an 1802 newspaper said al — it would have been a nightmare. For Woodrow Wilson, who revived the oral State of the Union partially because he believed the president should take a domineering role in the legislative process, it would have been a happy sight.

As the presidents between Jefferson and Wilson proved, there is no constitutional instruction that presidents address lawmakers in-person (or even annually), only that he “shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union.” Technically, the president only comes each year at the invitation of the House speaker.

Watching Democrats interrupting Trump — and not even moving from their seats to walk him to the chamber — I couldn’t help but wonder what might happen if Democrats win the House in 2026. Would a future Speaker Hakeem Jeffries even invite Trump to speak from the House chamber, or will the State of the Union address become yet another casualty of our polarized culture?

At times, it was hard to shake the feeling that the presidential speech to Congress had outlived its usefulness, crossing the boundary from informational address into full-on partisan theater. Maybe Jefferson’s way of doing business will have the last word after all.

I can both see how the spectacle was a scary sign of where we are, and also believe that this president has not EARNED respect. He is a traitor, liar, cheat, and autocrat, and I have zero interest in an opposition party that provides political cover for that by prioritizing "decorum." Personally, I would have preferred if Democrats simply boycotted or walked out en masse, which would demonstrate that they understand that it's just a rally for him and their presence achieves nothing.

I've always appreciated this blog standing for bipartisanship, but we are not in normal times. We are in the process of losing everything We The People have worked so hard to build: the social safety net we built to care for our seniors, children, and veterans; decades of medical research, critical weather science and disaster prevention, free expression via the First Amendment, a resilient economy, and the peaceful democratic world order. These are not normal times, so we have to respond differently.

I’d love if it went back to writing. I prefer reading to watching. At this point it feels like government has become a constant stage for political theater designed to entertain or shock Americans. Even the President has said multiple times that these conversations would make for good tv. It’s just nonsense.