From Pilgrims to Pluralism

How faith practices shaped the nation

Americans argue about many things, but few topics generate as much heat — or as much mythology — as religion. For centuries, we’ve told a simple origin story: the Pilgrims fled persecution, found freedom, built a shining city on a hill, and passed down a legacy of religious liberty that remains uniquely American.

That story isn’t wrong. It’s just incomplete.

Faith in America has always been more complicated, more contested, and far more diverse than we remember. Religion shaped our earliest settlements, our constitutional debates, our reform movements, our community norms, and even our holidays. It has both spurred our most inspiring fights for justice and been used as justification for some of our deepest injustices.

In other words, you cannot tell the story of America without telling the story of American religion.

And that story begins long before the Pilgrims ever stepped foot on the continent.

Before the Pilgrims: A Land Already Rich with Religion

When English colonists arrived in the early 1600s, the land they encountered was not spiritually empty. It was home to hundreds of Indigenous nations with distinct theological systems and ethics rooted in reciprocity, collective responsibility, and sacred relationships with the natural world.

The Iroquois Great Law of Peace, which shaped political structures for a confederacy of six tribes, would later influence American constitutional thought. The Hopi, Navajo, Powhatan, Wampanoag, and others maintained ceremonial calendars, rituals, healing practices, and traditions that had governed community life for thousands of years.

The United States often imagines its religious history as beginning with Europeans.

It did not. It began with the people already here.

The Colonial Patchwork: Thirteen Colonies, Thirteen Theologies

Contrary to popular imagination, the colonies were not founded on a shared Christian identity. They were founded on competing Christian identities, with the adherents of each convinced they were building the truest expression of God’s will. Each religious settlement brought its own traditions and expectations. In many colonies, church and state were deeply entwined. Official churches were established; attendance could be mandatory; taxes sometimes funded ministers.

A sampling of the religious variation between the colonies:

Virginia (Anglicans): Beginning with the Jamestown settlement in 1607, the Church of England became the established faith of what later became the Virginia colony. The House of Burgesses — Virginia’s general assembly — passed laws that formally adopted and governed a deeply hierarchical church aligned with political power, sustained by taxes and land grants.

Massachusetts Bay (Puritans): Founded in 1628, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was envisioned to be the Puritan “city on the hill” in service of “God Almighty,” wrote co-founder John Winthrop. In pursuit of that purity, the commonwealth was governed by strict moral codes, and mandatory church attendance. Dissenters like Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson were banished for questioning religious authority, an early reminder that freedom of worship was not yet universal.

Rhode Island (Baptists and dissenters): Founded because of Puritan intolerance. Banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635 for refusing to endorse state-enforced religion and unjust land seizure, Roger Williams founded Providence, RI, in 1636. There, he enshrined religious liberty in the colony’s official charter, declaring that “all and every person and persons may, from time to time, and at all times hereafter, freely and fully have and enjoy his own and their judgments and consciences, in matters of religious concernments.”

Pennsylvania (Quakers): Pacifist, egalitarian, religiously open. William Penn’s colony, founded in 1681, welcomed Jews, Catholics, and refugees long before tolerance was fashionable. Penn referred to the colony as his personal “Holy Experiment,” declaring to its inhabitants that they should “be governed by laws of your own making and live a free, and if you will, a sober and industrious life.”

Maryland (Catholics): Founded in 1632 by Lord Baltimore, the Maryland colony was established as a haven for English Catholics who were later pulled into Protestant–Catholic conflict.

What emerges from this map is not a unified “Christian nation” but a religious marketplace: colonies built on different doctrines, different visions of authority, and different interpretations of liberty.

This diversity forced colonists to confront a core democratic question long before independence: How do you build a society where people worship different gods, or the same God differently?

The Great Awakening — the First National Conversation about Freedom

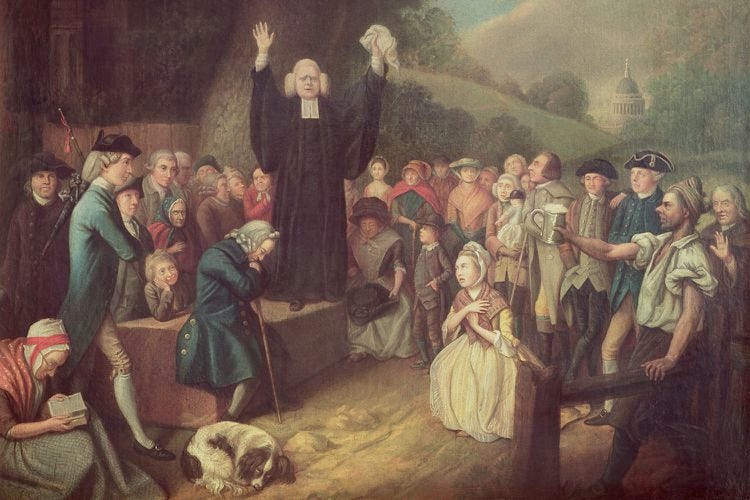

In the 1730s and 40s, the First Great Awakening ripped through the colonies. Evangelists like George Whitefield preached outdoors to crowds of thousands. Ordinary people — including women, enslaved Africans, and the landless poor — claimed spiritual authority outside the established churches found throughout the colonies.

Three radical ideas took hold:

Every person can experience divine truth directly. No priest or governor needed.

Religious authority must justify itself — constantly.

Spiritual equality hinted at social equality. If everyone could be saved, why couldn’t everyone vote?

Benjamin Franklin wrote that Whitefield’s sermons moved entire cities, filling the streets with people hungry for moral reform. Historian Thomas Kidd calls the Awakening “something incredible and unprecedented” that “helped to awaken America” to a recommitment of Christianity in the United States.

More importantly, it democratized another uniquely American trait: dissent.

The skills people learned in revival tents — public speaking, organizing, challenging authority — translated directly into the political dissents of the 1760s and 1770s that led to the American Revolution. When colonists later protested taxation or monarchy, they already had practice resisting illegitimate power.

Religion didn’t just inspire independence. It trained people how to be independent.

The Framers’ Dilemma: A Faithful People, a Secular Constitution

After independence, the Framers faced a faith paradox. Their new nation was undoubtedly intensely religious. But, they knew, a religious government could very well tear the nascent country apart.

Drawing on decades of colonial conflict, they designed something radical:

No national church.

No religious tests for office.

Free exercise for all faiths — including unpopular ones.

A clear ban on federal establishment of religion.

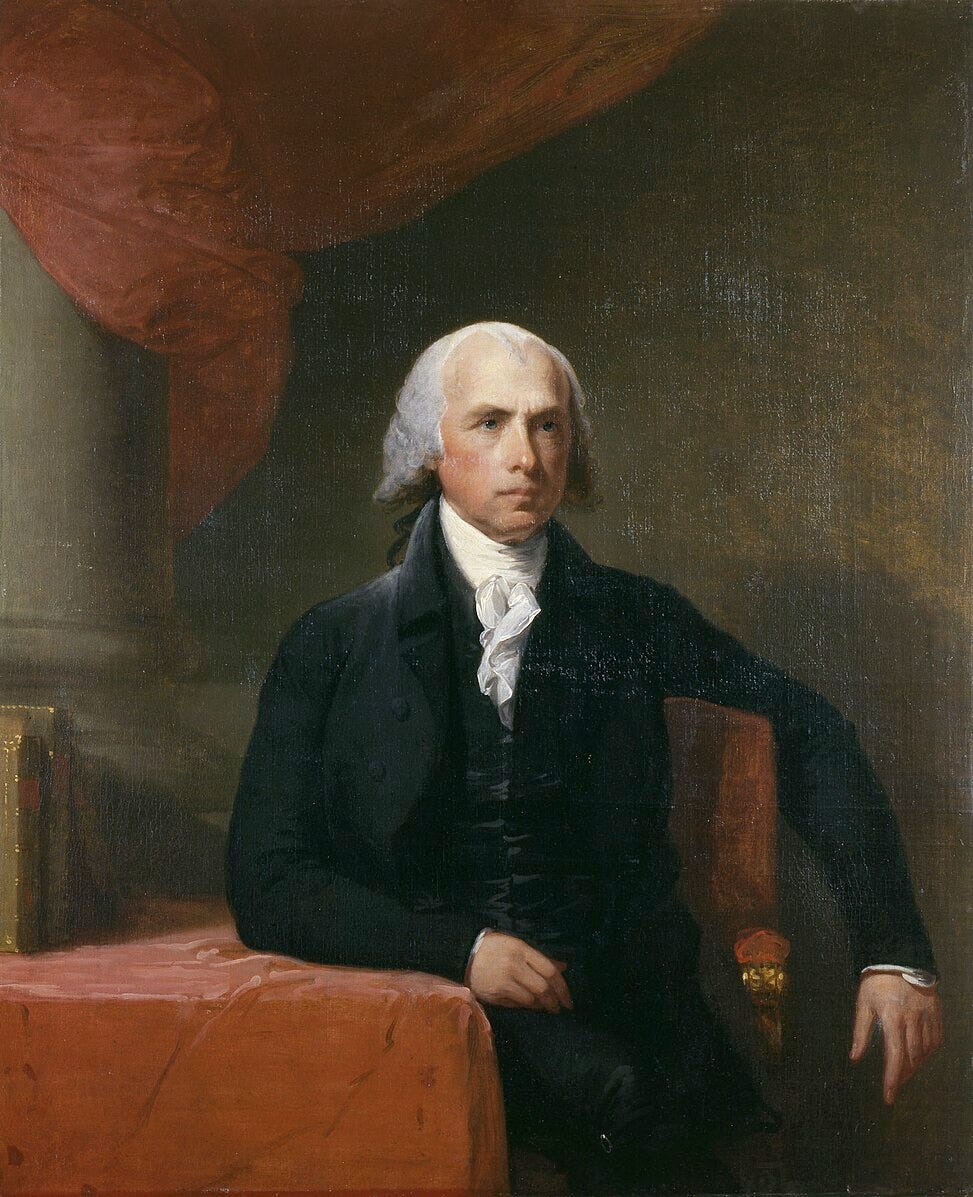

James Madison argued that true religion could flourish only when free of government coercion, writing, “The Religion… of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man.” Thomas Jefferson famously envisioned a “wall of separation between Church and State” to protect conscience from political power.

As a result, the Constitution and subsequent Bill of Rights did not create a Christian nation. In fact, its main aim was to protect citizens from the government’s establishing a national religion of any kind. The First Amendment promised that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” thereby guaranteeing a nation where Christians, Jews, Muslims, skeptics, and every faith in between (including none at all) could flourish without state interference.

This pluralism was not an afterthought.

It was a safeguard against the sectarian violence Europe had endured for centuries.

Faith as a Reform Engine: From Abolition to Civil Rights

If religion helped build the early republic, it also helped rebuild its conscience. Again and again, faith communities became the places where Americans wrestled with moral failure and imagined something better.

By the late 1800s, a new religious movement — the Social Gospel — insisted that faith required more than charity; it required justice. Urban ministers condemned unchecked industrial capitalism and argued that human dignity had to be protected in factories, tenements, and schools. Their activism helped inspire labor reforms, child-welfare laws, settlement houses, and the early architecture of the Progressive Era.

In the 19th century, churches were the beating heart of the abolitionist movement. Black congregations in Northern cities, Quaker meetings in Pennsylvania, and evangelical reformers across New England rooted their antislavery work in deep theological conviction. Frederick Douglass, an ordained minister himself, preached freedom as a divine mandate. Sojourner Truth blended testimony and prophecy. Harriet Tubman — “Moses” to the enslaved — trusted God with every mile she led people north via the Underground Railroad, often using church basements as railroad “stations” along the way.

And nothing shows the force of religious conviction in American history more clearly than the civil rights movement. Black churches were the strategic headquarters. Pastors provided the moral vocabulary. Christian scripture framed the case for equality. Dr. King’s call to form a “beloved community,” John Lewis’s getting into “good trouble,” and Fannie Lou Hamer’s fearless testimony all fused theology with democratic action — and changed the country.

Of course, religion has often been used to defend the status quo. But it has also powered some of the most transformative movements for equality in American history.

Faith in Daily Life: How Religion Quietly Shaped Our Norms, Schools, and Holidays

For all the ways faith fueled big national movements, its influence is just as evident in the routines and rhythms of everyday American life. Long before Congress passed sweeping reforms, religious communities were shaping how people gathered, learned, governed, rested, and even celebrated.

How Communities Behaved

Across the colonies and well into the 20th century, religious norms functioned as informal rulebooks.

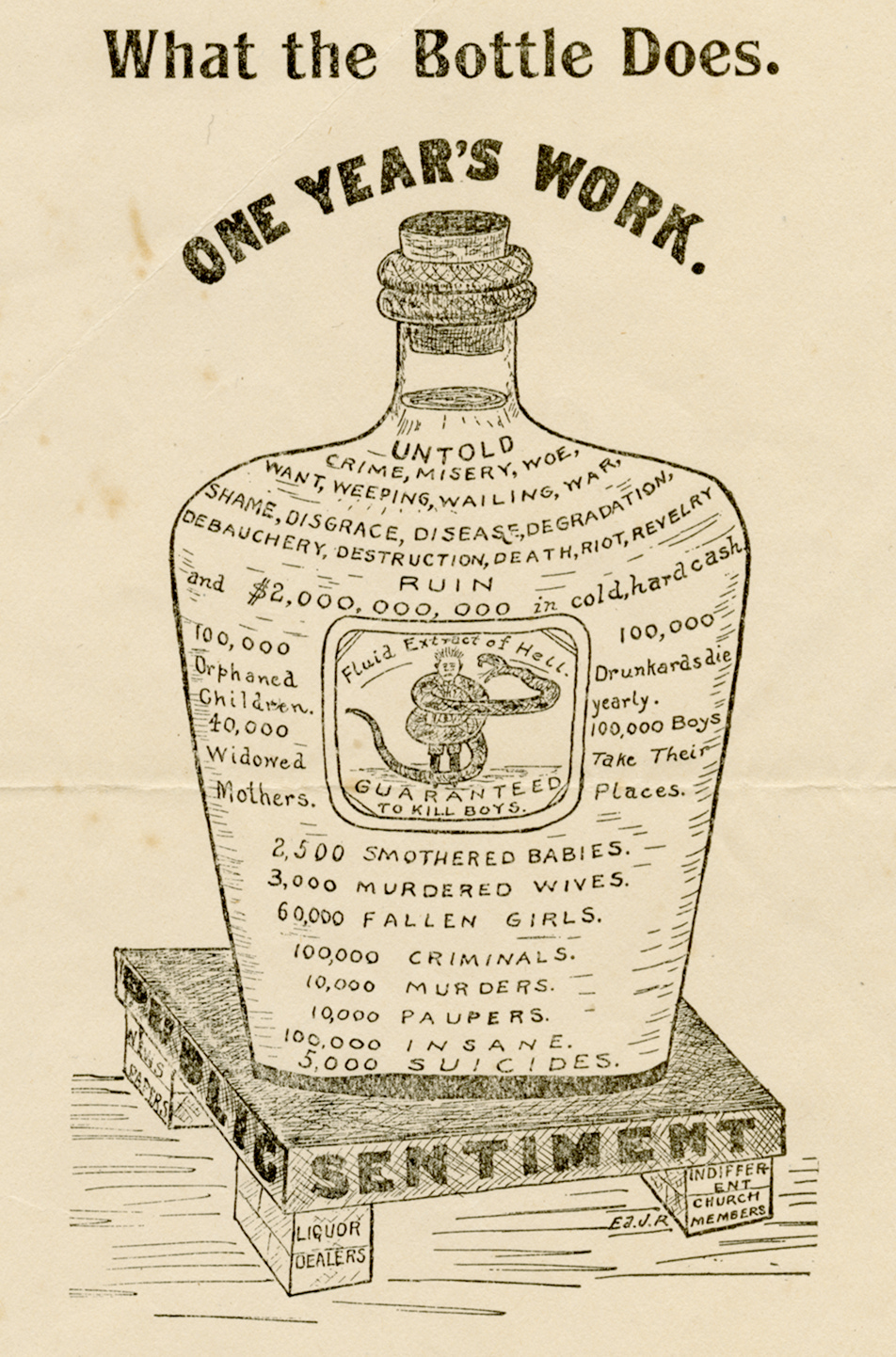

Sunday “blue laws” — which closed shops, banned certain forms of work, and restricted alcohol sales — were rooted in Sabbath observance and helped establish the idea that the nation should share a collective day of rest.

The temperance movement, launched by religious women’s groups like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, reframed alcohol consumption not just as a personal vice but as a social danger. Their decades of organizing built the political pressure that eventually led to Prohibition — and later helped inspire the public-health framing used in modern addiction policy.

Even civic habits we now consider entirely secular came out of religious traditions. Town meetings, mutual-aid societies, and early volunteer fire brigades all borrowed their structure from congregational governance — small groups of neighbors gathering to solve local problems as equals.

How Children Learned

Religion also built the foundations of American education, quite literally.

The earliest colleges — Harvard (1636), Yale (1701), Princeton (1746) — were built to train ministers and graduate biblically literate and devout students. Their curricula have since evolved, but the central idea that an educated citizenry was essential to self-government began in theology.

Before public schooling existed, Sunday schools functioned as literacy programs for working-class children. Their mission was religious, but their impact was civic: teaching reading, writing, and moral instruction to those who otherwise would not have had access.

And today, that legacy remains hiding in plain sight. Faith-based nonprofits run a massive share of America’s food pantries, homeless shelters, adoption agencies, refugee-resettlement organizations, and disaster-response networks.

How the Nation Celebrates

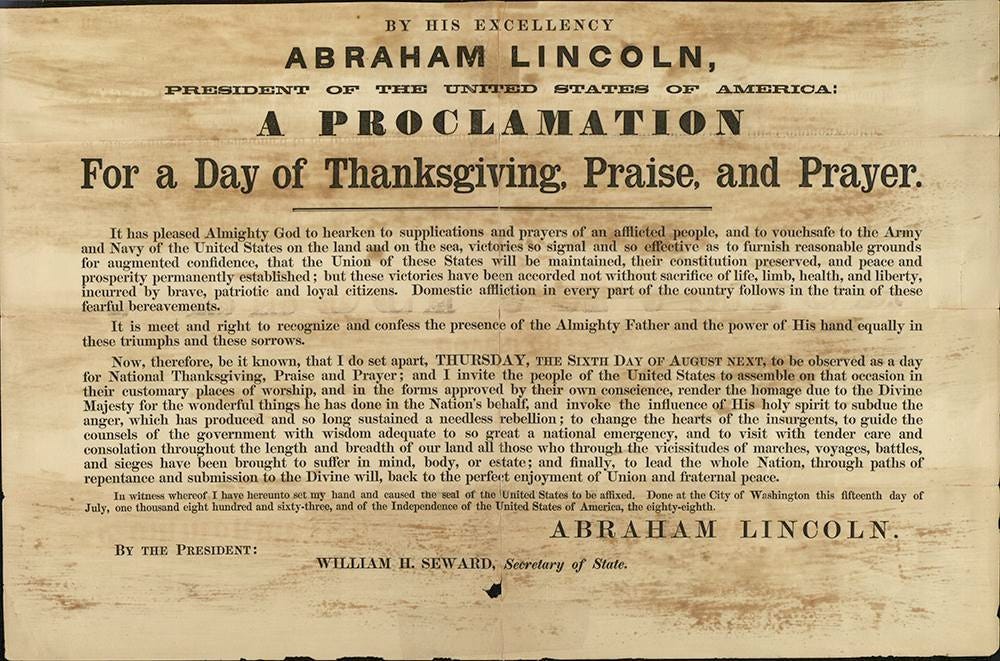

Religion also helped craft our civic calendar.

Christmas — now an economic and cultural giant — was once banned by Puritans for being too frivolous and too Catholic. It didn’t become mainstream until the 19th century, when German and Irish immigrants brought new traditions that softened its reputation and standardized celebrations across the country.

Hanukkah grew in prominence as Jewish immigration surged in the late 1800s and early 1900s, becoming a central ritual of American Jewish identity and public life.

And Thanksgiving — originally a regional New England harvest festival — became a national holiday only during the Civil War. In 1863, after years of lobbying from religious writer Sarah Josepha Hale, Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for a national day of gratitude and unity. A local tradition, shaped by faith, became a binding civic ritual.

Faith didn’t just shape the grand arcs of American history. It shaped how communities cooperated, how children were taught, how neighbors cared for one another, and how a diverse nation learned to celebrate together. In small ways and large ones, religion has been woven through the daily fabric of American life — not always visible, but always present.

The Pluralism Revolution: America Remade by Immigration

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mass immigration transformed the country’s religious landscape. Millions of newcomers arrived not only with languages and cuisines, but with faith traditions far outside the Protestant mainstream.

Catholics fleeing famine-era Ireland and southern Italy built the parishes that still anchor Boston, New York, and Chicago. Jewish immigrants escaping pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe established synagogues, Yiddish schools, and mutual-aid societies that reshaped urban civic life. Asian immigrants brought Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and later Sikhism — traditions that took root despite exclusion laws aimed at shutting them out.

None of this happened quietly.

Catholics were met with riots and “No Irish Need Apply” signs. Jews faced housing covenants and university quotas. Chinese and Japanese immigrants endured blanket federal bans that excluded entire populations because of their ethnicity and beliefs.

And yet, over generations, these communities remade the country. They constructed temples, mosques, synagogues, cultural centers, and charitable networks that turned American cities into some of the most religiously diverse places on earth.

That diversity is no longer an anomaly. It’s one of our greatest civic inheritances.

A New Chapter: Faith in the 21st Century

Religious affiliation and devotion in America have changed markedly in recent years. According to the 2023–24 Pew Research Center (PRC) Religious Landscape Study, about 62% of US adults now identify as Christian, down from 78 % in 2007 — but roughly stable over the past five years. At the same time, those who describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated — atheists, agnostics, or “nothing in particular” — now make up about 29% of adults and the fastest growing cohort in the country.

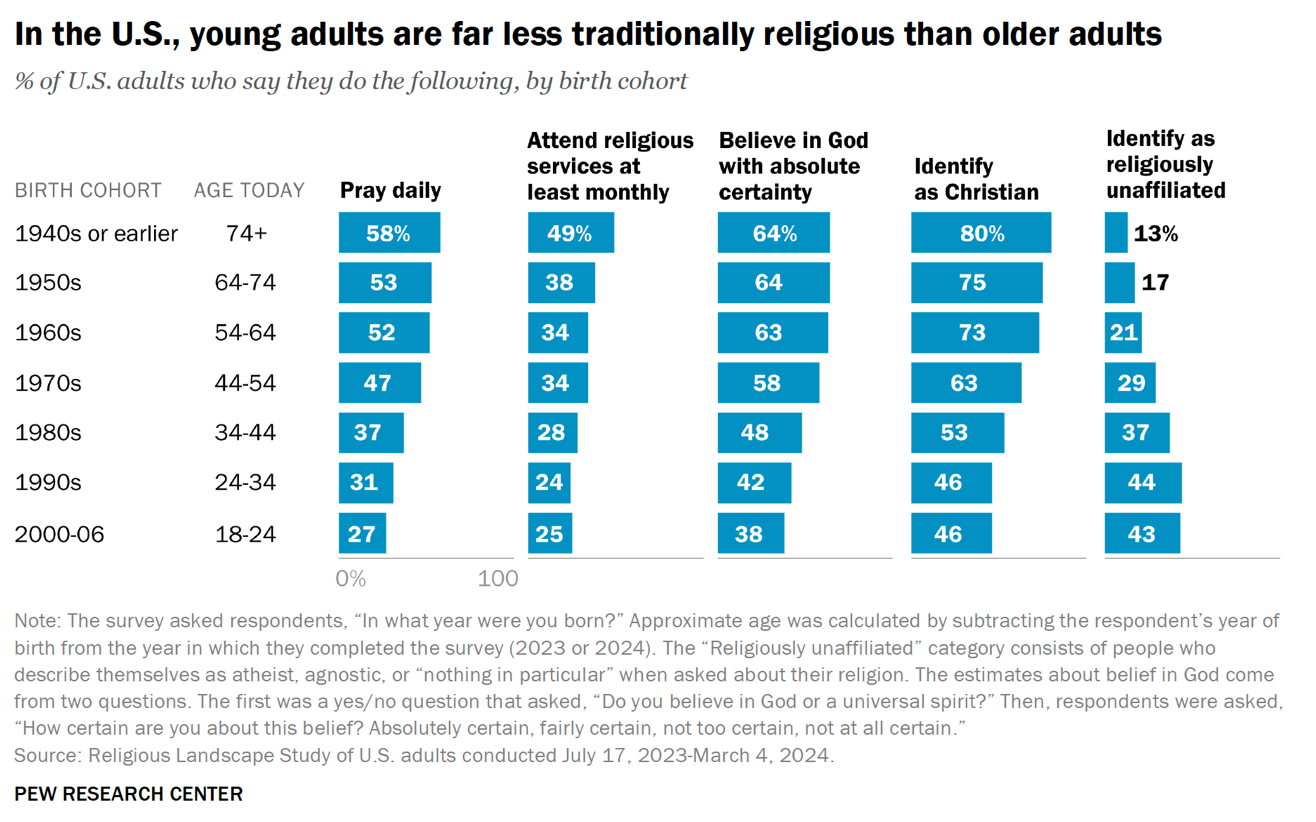

More strikingly, a fresh poll from Gallup finds that only 49% of Americans say religion is “very important” in their daily lives, a 17-point drop since 2015 and among the largest declines the organization has recorded globally. And as the figure below shows, each successive generation in America is markedly less likely to pray daily, attend religious services, believe in God with certainty, or identify as Christian — and far more likely to be religiously unaffiliated.

These shifts reflect a larger transformation in how Americans relate to faith. The landscape isn’t merely shrinking; it’s decentralizing religious institutions, as well.

Interfaith marriages, blended spiritual practices, and “spiritual but not religious” identities are more common than ever.

Many who grew up with church attendance now express belief outdoors of formal institutions — in community service, activism, meditation, or informal spiritual practices.

Religious commitment is increasingly divorced from traditional worship: while formal church attendance has dipped, belief in a higher power, spirituality, or moral values remains robust. In the 2025 PRC study, 83 % of respondents said they believe in God or a universal spirit, and about 70% said they believe in heaven or hell.

In short, faith in America isn’t dying, it’s being reimagined. Instead of pews and pulpits, spiritual expression and moral engagement are finding new forms. After four centuries of change, religion remains a living, evolving part of American life — less monolithic, more individual, more fluid — and ever responsive to the times.

A Country Built on Conscience, Still Learning to Honor It

From the Puritan meetinghouse to the Black church, from the synagogue to the longhouse, from revival tents to civil-rights marches to today’s interfaith coalitions, religion has been one of the most powerful, and complicated, forces in American life. It has justified oppression and fueled liberation. It has sown division and cultivated belonging. It has shaped our laws, our movements, our holidays, our neighborhoods, and our shared imagination of what this nation might become.

If there is a single thread running through that history, it’s this: America has always been a place where many faiths, and no faith at all, are asked to build a civic home together.

Pluralism isn’t our backup plan.

It’s our oldest project.

And every generation, including our own, is still learning how to carry it forward; imperfectly, creatively, and with the same mix of conflict and hope that defined the country from the beginning.

I need to come back to finish this piece but this weekend I was able to tour one of the older colonial churches in Virginia. It's Ware Church in Gloucester, VA and the church itself was started in 1652, the building we were in dates to 1719. https://warechurch.org/our-history The walls were 2.5 feet thick. Can you imagine the effort it took in 1719 to build that? It's so interesting to read about the history of the colonial era. I have never read much about the religions of Native Americans and now feel like I need to find a great book about that!

A very thoughtful piece on the affects of religion in America today and hopeful, too. In my own experience , the thought of respecting each others beliefs is paramount and finding common ground in seeking a better world for everyone in our country must be sought and fostered by all of us in hopes of producing a more perfect union in our country and as a continued example by We, The People to the rest of the world population, as well.