Forty-Eight Emergencies and Counting

If a president can call anything an emergency, does the word have any meaning at all? And who, if anyone, can stop them?

Today's issue is sponsored by the Pew-Knight Initiative

The United States is in a constant state of emergency, at least according to President Trump.

The southern border is “under attack.” Trade deficits pose an “unusual and extraordinary threat.” A Venezuelan gang has “invaded” the country. And the nation’s capital is overrun with “lawlessness.”

Since returning to office in January, Trump has repeatedly sought to expand his authority by taking advantage of a suite of laws that give the president enhanced powers in times of crisis or emergency. Chief among them is the National Emergencies Act, which Trump has invoked nine times in 2025, more than any previous president used it in a single year.

But how do these emergency powers work? And do they come with any limits? Allow me to explain.

What is a national emergency?

Political theorists have long struggled with a difficult conundrum. Democratic republics like the United States are built on the idea that a president should only be able to assert authority that’s been given to them by the Constitution or by law. But there are always going to be circumstances the law can’t predict, or that legislators can’t act on quickly enough to address, like an imminent attack.

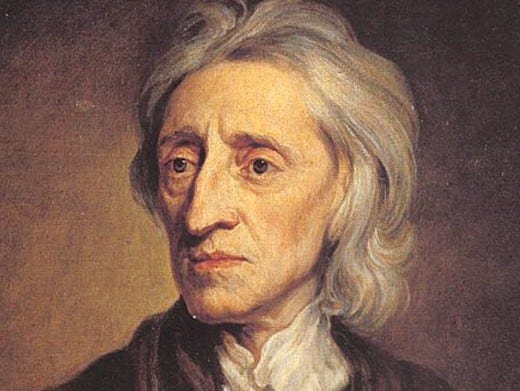

That’s why most countries, even ones that divide authority between different branches of government, accord some form of emergency power to the executive. Legislative bodies are simply “too numerous” and “too slow” to address crises, John Locke wrote all the way back in 1689, and “it is impossible” for the law “to foresee” everything that might befall a country.

Locke believed that meant the executive should sometimes be able to act “without the prescription of the law, and sometimes even against it.” Abraham Lincoln agreed. “Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated?” he asked in 1861.

For most of US history, it was broadly recognized that presidents could occasionally invoke emergency powers — and several did, from Lincoln to Woodrow Wilson to FDR — but there wasn’t much of a comprehensive structure governing the process.

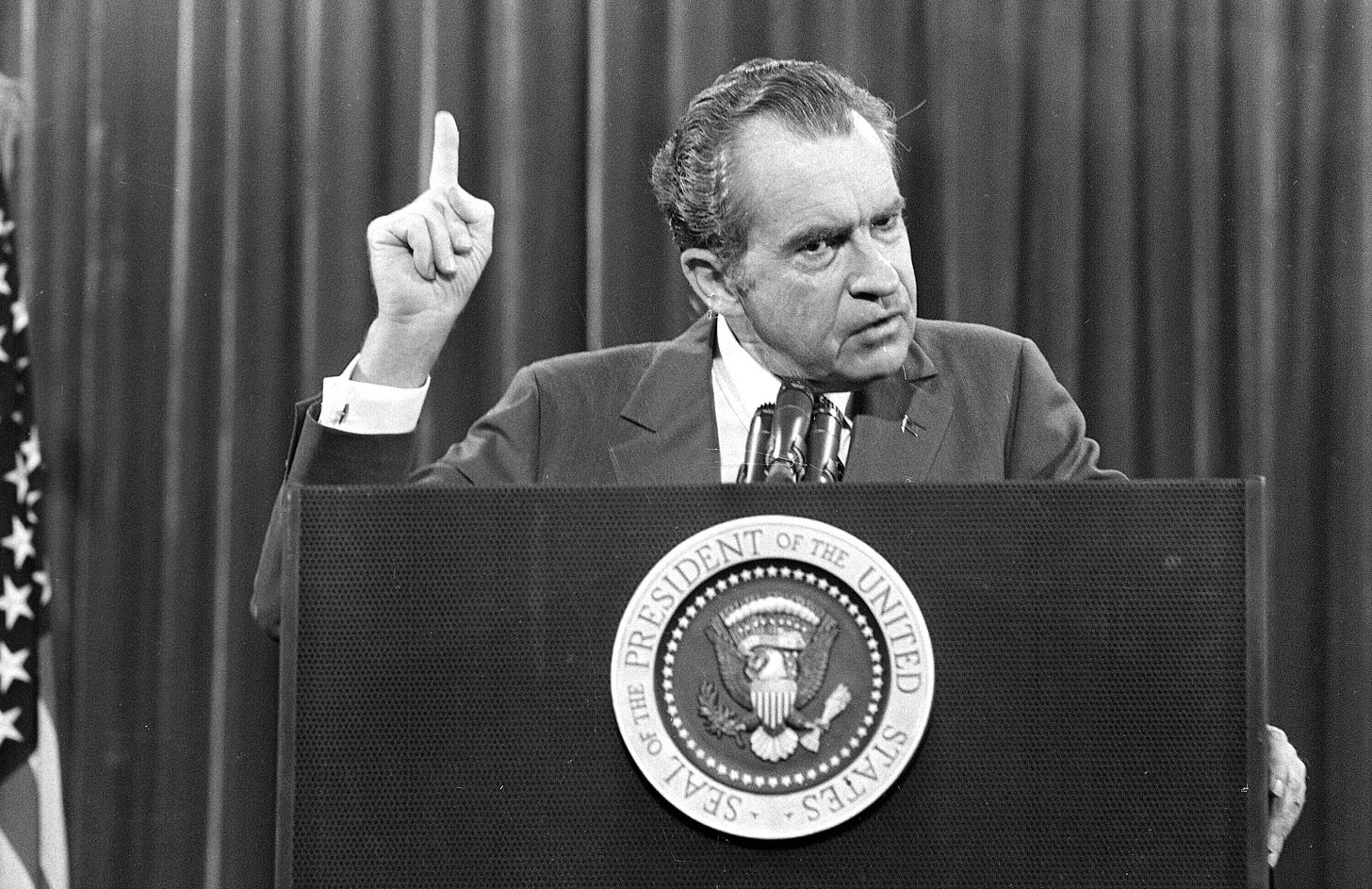

That is, until one president pushed a bit too far. In 1973, Richard Nixon was squabbling with Congress over funding for his military operations in Cambodia when he made an extraordinary threat: If lawmakers didn’t approve the spending he was asking for, he would move ahead with the operation anyways, invoking emergency powers that had been accorded to the president by a forgotten Civil War–era law.

That threat inspired Congress to comb through, for the first time, the emergency powers it had delegated to the White House.

It wasn’t an easy task.

Nowadays, the entire US Code is available online; all it takes is a simple “CTRL+F” to search it. Back then, not so much.

At the time, the only searchable database of federal law was located at an Air Force facility in Colorado. The Senate created a special committee to examine the US Code, searching for words like “emergency,” “invasion,” and “insurrection.”

The panel ultimately found more than 470 different emergency powers that Congress had granted to the president.

Wanting to organize the procedure for when the president could use these powers — and when Congress could intervene — they came up with the National Emergencies Act (NEA), which was eventually signed into law by Gerald Ford in 1976.

Here’s what the NEA does: It requires presidents to provide public notice when they are declaring a national emergency. It sets those declarations to sunset after a year by default. And it sets out a process for Congress to overturn them.

But here’s what it doesn’t do: actually explain what powers an emergency declaration gives the president.

That is still left to a buffet of other laws, which lay out the various powers a president is accorded when he declares a national emergency. The full list has been compiled here by the Brennan Center for Justice; it includes everything from waiving laws regarding the disposal of garbage at sea to prohibiting the export of any agricultural commodity.

Laws on the list also allow the president to authorize “military construction projects” (which Trump did to build more border wall in response to his border emergency) and to “regulate… importation” (which he did when implementing his “Liberation Day” tariffs in response to the trade deficit emergency).

What constitutes an “emergency,” the vague circumstances when the president is given these expanded powers? The NEA doesn’t say, and neither do most of the other laws. I went searching for the legal definition of an “emergency,” but it turns out there isn’t one. (Indeed, even Congress’s research arm cites only the Merriam-Webster definition when explaining the NEA.)

At first glance, an emergency would appear to be whatever a president says one is.

Other laws Trump has used to claim emergency-like powers, outside the auspices of the NEA, are similarly vague. The Alien Enemies Act, which he invoked in an attempt to deport members of a Venezuelan gang without due process, bequeaths new powers on the president when an “invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened” against the US “by any foreign nation or government,” without offering more detail on what counts as an attempted invasion.

The District of Columbia Home Rule Act, which Trump used last week to declare a “crime emergency” in the nation’s capital, allows the president to assert control over the DC police when “special conditions of an emergency nature exist.” No further explanation given.

So, can an emergency declaration be second-guessed?

The original idea of the NEA was that Congress would be able to terminate a presidential emergency declaration with a simple majority vote of both chambers.

But that was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1983.

So, now, for Congress to end a presidentially declared national emergency, both chambers have to pass a joint resolution. That still requires only a majority vote — no filibuster in the Senate allowed — but it also means the president can veto the resolution.

Let’s say that President Popeye declared a national emergency based on the fact that the US was suffering from a severe spinach shortage, which meant that he should be allowed to assert special powers. Congress, thinking that a lack of spinach doesn’t quite qualify as an emergency, might vote to terminate the declaration… but the resolution would be sent back to Popeye, who would promptly veto it.

Two-thirds votes would then be required in each chamber of Congress to override the president’s veto, a high bar in these polarized times.

From the Pew-Knight Initiative:

If you were to guess what percentage of Americans regularly follow the news, what would you say? 50%? More? Less? You might be surprised to see the numbers. A fascinating study from Pew Research Center’s Pew-Knight Initiative explores the changing dynamics of news, especially as digital and independent news sources grow.

The news today is not what it used to be… and Americans have a lot of thoughts on it.

Click here to read more!

In 2019, majorities of both the House and Senate voted to overturn a border emergency declaration issued by Trump. But when he responded with a veto, the joint resolution lacked the two-thirds support to override.

The next backstop envisioned by the NEA was that emergency declarations would automatically end after a year, unless the president renewed them. But the framers of the legislation didn’t anticipate that each president would simply renew existing emergencies each year.

Not to alarm you, but we are currently living under no less than 48 active national emergencies. The longest-running dates back to November 1979, when Jimmy Carter declared a national emergency — renewed annually by every president since — in response to the Iran hostage crisis, allowing him (and his successors) to impose financial penalties on Tehran.

Can something be an emergency (dictionary definition: “unforeseen,” “immediate,” “urgent”) if it has lasted for 45 years (and if the hostage crisis that sparked it has been over for 43)? According to US law: yes.

The NEA also requires Congress to vote every six months on whether active national emergencies should remain in effect. Congress, opting to ignore itself, has basically never done that.

None of us this would have bothered our friend Locke. He recognized that an executive might abuse their emergency powers, but because the legislature would never move quickly enough in a crisis, he didn’t think there was anyone (save God) who should be able to second-guess an executive’s use of emergency powers.

“There can be no judge on earth” for this question, he wrote. “The people have no other remedy in this… but to appeal to heaven” for rulers who will use emergency powers wisely.

However, in the US, we do have another branch of government besides the executive and the legislature — and their whole job is to be “judges on earth.” If the president tries to declare an emergency, can the courts rule that the situation in question doesn’t fit the (admittedly vague) legal standard?

That’s a question we’re finding out the answer to right now. The Trump administration has argued that this question is “non-justiciable,” meaning that courts cannot decide it. In the tariffs case, for example, a court can review whether Trump acted correctly in how he responded to the trade deficit emergency, they argued, but it can’t question whether such an emergency exists in the first place.

Last month, during oral arguments in the tariff case that I attended, several federal appeals court judges seemed skeptical of that argument.

When a Justice Department attorney asserted that tariffs did have legal limits (because they could be issued only in response to an urgent threat) but that the threat couldn’t be examined by the court, one judge responded: “If they’re not reviewable, how are they limits?” It was also noted at the hearing that the president’s own executive order called trade deficits “persistent,” undercutting the notion that they posed a sudden emergency.

Federal judges have also questioned the basis for Trump’s use of the Alien Enemies Act, which asserted that the Venezuelan government had directed the gang Tren de Aragua to invade the US.

The president has not demonstrated that there is an “organized, armed group of individuals entering the United States at the direction of Venezuela to conquer the country or assume control over a portion of the nation,” Judge Fernando Rodriguez, a Trump appointee, wrote in May. Therefore, he ruled, there is no “invasion” and the powers Trump is trying to access under the AEA are not legally available to him.

Similarly, in the DC crime case, Judge Ana Reyes, a Biden appointee, said last week that she planned to hold an evidentiary hearing to fully examine whether Trump’s proclaimed “crime emergency” was supported by crime statistics in the city. The president couldn’t just declare an emergency willy-nilly without some consideration of the facts and data, she seemed to be suggesting.

The next time a Democrat is in the White House, I imagine there will be great pressure on them to take advantage of Trump’s use of emergency powers — and declare a national emergency to address climate change, or abortion rights, or other progressive priorities.

But instead of allowing an escalating tit-for-tat of emergency powers, hopefully lawmakers will take inspiration from the National Emergencies Act, which was written by two senators — Democrat Frank Church and Republican Charles Mathias — who believed that a president’s powers should be checked, no matter which party they belonged to.

There is already a bipartisan bill to further reform emergency powers: the ARTICLE ONE Act, which was written by Reps. Chip Roy (R-TX) and Steve Cohen (D-TN). Instead of a national emergency continuing unless Congress votes to end it, the bill would make it so that a national emergency ends unless Congress votes to continue it.

Under the bill, every national emergency declaration would last 30 days unless Congress extended it. The measure would also require the president to transmit a report to Congress for every emergency, with a specific explanation of the circumstances that required the emergency.

In something of a surprise, the bill was approved unanimously by a House committee last year. It was formally sent to the House floor in December 2024, a month before Trump took office. It was never voted on.

This is an example of the continued perversion of the rule of law. Trump and MAGA are going to continue to push the envelope to consolidate power and wield it for their gain. This is fascism plain and simple. I’m increasingly feeling worried about the midterms. Is there an emergency declaration he can make to delay elections? Also, I’m still so angry with the Americans who allowed this to happen and are celebrating this administration. There is SO much evidence at this point to see that what is happening is highly abnormal and destructive.

The constant "emergency" outcry is watering down those things that warrant the declaration. Foolishness on full display.