Don't Eat the Raccoon!

The White House has seen some unusual November holiday happenings

The Thanksgiving holiday is one traditionally celebrated by gathering with family and friends around a large feast — maybe your family has their own favorite activities, like watching the parade or playing a game of football.

As with all traditions, Thanksgiving has taken a long time to evolve into its current state of celebration. So today I am sharing an episode of Here’s Where It Gets Interesting, where I talk about when and how it actually became a federally acknowledged holiday. And just for fun, we'll take a look at some of the ways Thanksgiving has been celebrated in the White House over the years.

Spoiler alert, there's a raccoon involved.

So either take a listen on whatever platform you enjoy podcasts on, or you can read through the whole story below.

During the 1600s, the relationship between colonists and indigenous tribes was full of tension and complexity as settlers began to take native land for their own agricultural uses. It is much too nuanced to be summarized by the supposed sharing of a harvest meal.

We do know that there wasn't just one shared feast like we often learn in schools. Autumn festivals were held yearly in many different settlements in the colonies to celebrate a bountiful harvest. And this was not a unique practice that was brought to America by European settlers. Indigenous tribes had long held their own harvest ceremonies and rituals.

The practice of observing a day of gratitude continued sporadically for the next 100+ years. In 1789, a man named Elias Boudinot, who was a member of the House of Representatives from Massachusetts, advocated that a day of Thanksgiving be held to thank God for giving the American people the opportunity to create a constitution to preserve their hard-won freedoms.

And a Congressional Joint Committee approved Boudinot’s motion. In October, George Washington made the proclamation that the people of the United States would observe a day of public thanksgiving and prayer later that fall on Thursday, November 26th. But the holiday was still a far cry from the annual federal holiday it is today.

But isn’t it interesting that in its own earliest cohesive observation, the celebration was meant to appreciate not a bountiful table, but the freedoms of a newly formed democracy? Future presidents like John Adams, James Madison, and James Monroe, all followed in Washington's footsteps and declared a day of Thanksgiving during their terms in office.

Thomas Jefferson, however, did not comply. He believed it was a conflict of church and state to require the American people hold a day of prayer and thanksgiving. And so he simply chose to not make it a thing. Over time, the habit lost traction and no other president brought up a recognized day of thanks until President Abraham Lincoln in 1862.

Most of the credit for the establishment of a nationally celebrated Thanksgiving holiday can be given to one person, a woman named Sarah Hale. Sarah was a magazine editor who began a campaign in 1827 to formally recognize Thanksgiving as a holiday. She published stories and recipes about how to celebrate a National Day of Gratitude and she wrote hundreds of letters to anyone she thought would have some sway in the matter: Governors, senators, multiple presidents.

But Sarah Hale wasn't just a small-time editor who bothered politicians with her relentless idea about Thanksgiving. She was one of the most influential women of the 19th century. The Anna Wintour of her time. She was born on a small New Hampshire farm in 1788, and her mother gave her basic schooling, but it was her older brother, Horatio, who guided her education beyond writing and needlepoint.

Her brother was a student at Dartmouth and he shared his books and class subjects with her so that she could learn at an Ivy League level. Sarah was teaching in a local school when she married a young lawyer named David Hale. David was Sarah's love match, and he encouraged her to pursue her passions, especially writing.

And together with a circle of friends from David's Freemason Lodge, they started a small literary club. Sadly, David died after suffering from pneumonia in April 1822, just nine years into their marriage. So Sarah found herself a widow at age 34 with five young children to support. The couple's tight knit group of friends came through for Sarah and they helped her set up a millinery business that would give her a way to independently support herself and her children.

There, she and her sister-in-law made and sold hats together. Arguably though, it's what happened next that changed the course of Sarah's life. The same supportive family friends pooled their money together to get one of Sarah's little books of poems published. The volume of poetry was pretty successful, enough so that it allowed Sarah to take a break from her millinery business and concentrate on writing.

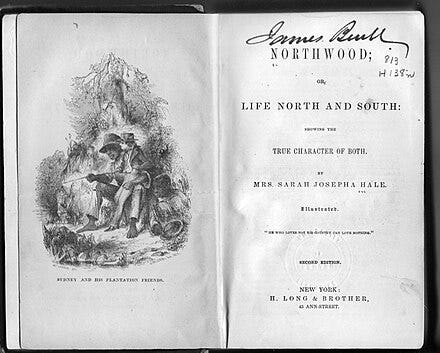

She wrote a novel called Northwood, which was one of the first novels that wrote directly about the question of slavery in America. It supported the Back to Africa movement, a movement that sought to free enslaved people and give them passage back to their countries of origin. The movement did not catch on as Sarah might have hoped.

Most enslaved people did not want to resettle back in Africa, but it was a fairly well known early emancipation strategy considered by abolitionists. You can still read Northwood — the novel is in the public domain and there are a number of places online where you can read it in its entirety if you want to.

Northwood was popular and it gained the attention of the Reverend John Blake, an Episcopal minister and headmaster of the Cornhill School for Young Ladies. Blake was starting a new ladies magazine in Boston, and he asked Sarah to serve as its editor. Sarah accepted his offer and moved from her home in New Hampshire to Boston in 1827.

Of note, however, is that Sarah left behind four of her five children, and while she continued to visit and support them financially, they were raised by family members in New Hampshire. As editor of John Blake's Ladies Magazine, Sarah began writing most of the material for each issue herself. She tackled everything from book reviews, sketches of American life, fashion advice, persuasive essays, and poetry, and she did not shy away from sharing her opinions.

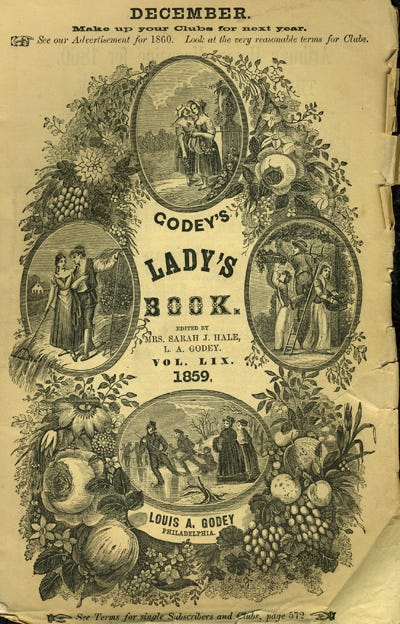

She regularly impressed upon her readers the importance of women's education. She stopped short of considering herself a supporter of women's equal political involvement, but she firmly believed women should be allowed to work toward their own economic independence. In 1837, Louis Godey bought Ladies Magazine and changed its name to Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Sarah remained on as an editor for another 30 years, and during that time she grew hugely influential as an arbiter of good taste and manners. She had a keen eye for discovering writing talent and often published pieces by emerging American writers like Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, Edgar Allan Poe, Henry David Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. She also continued to publish her own work, including a small volume of poetry that contained her most famous piece. A verse you have likely had memorized since childhood.

And the poem? Mary Had a Little Lamb.

So your new party fact is, the woman who wrote Mary Had a Little Lamb is also responsible for turning Thanksgiving into a national holiday. For 36 years, Sarah persisted in writing regular letters to influential leaders and every US president with her one request. That the last Thursday in November be set aside to, she wrote, offer to God our tribute of joy and gratitude for the blessings of the year.

And on October 3rd, 1863, Sarah Hale finally got her holiday. With his spirits high after the Union victory at Gettysburg, President Lincoln issued a proclamation declaring that the last Thursday of November shall be National Thanksgiving Day. He ordered all government offices in Washington to be closed in observance.

President Lincoln and his son Tad, who was 12 at the time, are also credited with the first turkey pardon, also in 1863, even though it was originally done for the Christmas holiday. A reporter later said that a live turkey had been brought home for the Christmas dinner, but Tad interceded on behalf of its life. And his plea was admitted and the turkey's life spared.

But the practice of unofficial turkey pardon didn't begin until much, much later. Most presidents spent their time in office graciously accepting their Thanksgiving turkeys and roasting them up for dinner.

Private American citizens began gifting turkeys to US presidents as far back as 1873 when the Poultry King of Rhode Island, a man named Horace Vance, began selecting his choicest birds and sending them to the White House. Vance continued this tradition, sending turkeys for both Thanksgiving and Christmas, for nearly 40 years until his death in 1913. For the next three decades, people from all over the country began to step in and fill Horace Vance's shoes.

In 1922, during President Warren G. Harding's last Thanksgiving at the White House, the Harding Girls’ Club of Chicago fattened up a turkey on a diet of chocolate and sent it on a road trip from Illinois to Washington, DC.

The Harding Girls’ Club sent turkeys to the president wherever he was. One year, the president was on his way to Panama to visit the Panama Canal and they sent a turkey named John Gobbler. The next year the turkey flew on a plane with a military guard wearing an aviator costume including a helmet, goggles, and a sweater coat.

And in another year, they made arrangements for the turkey to travel by train to Washington, DC. Florence Harding, Warren Harding's wife, was going to personally pick up this turkey that had been transported all the way across the country via train, because that's how fun this tradition had become.

The turkey on the train traveled more than 800 miles in under two days, and it made front page news all over the country. A newspaper in Atlanta noted that the turkey had traveled comfortably in a motor coat that was made especially for him and an extra large cage suspended by and set on springs to prevent too much shake up on the trip — you would not want the turkey to arrive shaken.

And the next year when president Calvin Coolidge took office, he pleaded for people to stop the practice of sending turkeys to the White House. But the Thanksgiving poultry kept showing up, and things started to get weird.

In 1926, President Calvin Coolidge received his most unusual Thanksgiving meal option from a supporter in Mississippi. It was a raccoon. And needless to say, the Coolidges declined to dine on roasted raccoon for their Thanksgiving dinner. Instead, they named the raccoon Rebecca, and they kept her as a family pet.

For Christmas that year, President Coolidge had a custom collar made for her with the words “White House Raccoon” embroidered on it. The family kept Rebecca for the rest of their tenure in the White House. And they eventually gave her a playmate named Ruben.

Only twice since Lincoln declared Thanksgiving an official holiday has a president changed the day of observation. In order to give Depression-era merchants more opportunity to make sales before Christmas, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt bumped up the observance of Thanksgiving to the third Thursday in November in both 1939 and 1940.

The change was short-lived after some states decided to adopt Roosevelt's date change and others didn't. Citizens complained that the date confusion interfered with popular Thanksgiving Day events like football games and parades. And by the time Thanksgiving came around in 1941, a congressional joint resolution declared the fourth Thursday of November as the official date of Thanksgiving, and Roosevelt signed it.

A few years later in 1947, the National Turkey Federation cleared up the rules around another holiday tradition. Gone were the days of unsolicited live turkeys showing up at the White House from well-meaning people. The National Turkey Federation took on the role of the official turkey supplier to the president, and that year they delivered a whopping 47 pound bird to Harry Truman in time for the president's Christmas dinner.

To celebrate the National Turkey Federation's new partnership, The White House held a turkey receiving ceremony in the Rose Garden, a tradition that has continued ever since. The photos that circulate every year of the president with a turkey? Those are far more likely to be from this turkey receiving ceremony than from the pardoning tradition, which didn't become an annual tradition until 1989, after President George H.W. Bush remarked, “Reprieve. Keep him going. Or pardon. It's all the same for the turkey, as long as doesn't end up on the president's holiday table.” Before that, President John F. Kennedy pardoned a turkey meant for his table in 1963, and some of his successors did the same, but only occasionally.

In 1953, when Dwight Eisenhower took office, Mamie Eisenhower took over the role of First Lady. And she was given complete control over the finances and scheduling of the home. Mamie did not mess around. She was known to routinely spend time clipping coupons to give to her staff before they did the shopping.

It's difficult to imagine a modern First Lady clipping coupons, but Mamie was relatable. Housewives around the country appreciated her capacity to decorate and throw a dinner party on a budget.

And even by her first Thanksgiving in the White House, she had the eyes and ears of America, and they went crazy for one thing: Mamie's recipe for pumpkin chiffon pie. The White House got so many letters asking after Mamie's deviation from the traditional recipe that she directed her social secretary to respond to each one by supplying a copy of the recipe.

Instead of the usual custard based pie, Mamie's recipe calls for a ubiquitous post war food additive to stabilize it. Gelatin. Newspapers and magazines across the country reprinted the recipe every Thanksgiving.

The Associated Press food editor gushed that, “Our tasters, finishing their last mouthfuls with blissful satisfaction, declared it ‘the very best of its kind.’” And for six out of eight Thanksgivings during her tenure as First Lady, Mamie spent the holiday at the Eisenhower's personal retreat, a tidy home dubbed “Mamie's Cabin” on the grounds of the Augusta National Golf Course in Georgia.

Thank you so much for reading today (or listening) while you prepare food to share or travel to visit your family.

I am honored to be a part of your holiday routine. I am thankful for you. And I’ll see you again soon.

Thank you for this Thanksgiving treat! I’m going to play it for my grands when we drive around today delivering their acorn cookies to friends and neighbors.

Acorn Cookies:

Use chocolate frosting to attach the flat side of a Hershey kiss to the flat side of a mini vanilla wafer.

Attach a butterscotch chip to the top of the wafer.

Share with the message to be:

Just.

Peaceful.

Good.

And Free.

(Turkey hand drawing optional)

Thank you Sharon and know how grateful we are for you & your light. Your stories will be a fabulous talking point for Thanksgiving meals. Happy Thanksgiving to all.