Do Medicaid Work Requirements Work?

They've been tried before.

Together with:

Republicans are advancing some of the biggest cuts to Medicaid in the program’s history with the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the landmark package implementing President Trump’s legislative agenda.

But to hear House Speaker Mike Johnson tell it, the measure makes only a few cosmetic changes.

“No one has talked about cutting one benefit in Medicaid to anyone who’s duly owed,” Johnson has told reporters. “What we’ve talked about is returning work requirements, so, for example, you don’t have able-bodied young men on a program that’s designed for single mothers and the elderly and disabled. They’re draining resources from people who are actually due that. So if you clean that up and shore it up, you save a lot of money and you return the dignity of work to young men who need to be out working instead of playing video games all day. We have a lot of fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicaid.”

The first thing to note is that this changes the definition of “duly owed.” Under Medicaid as it is presently constituted, there is no work requirement for beneficiaries, so an unemployed recipient is not defrauding or abusing the program or receiving a benefit they aren’t owed by law.

However, it’s true that the program was originally intended primarily for low-income families and disabled people; it wasn’t until the Affordable Care Act that the program was expanded to include more low-income, able-bodied Americans without children. Reasonable people can disagree about whether such individuals should be required to work as part of the program; indeed, many Americans of both parties support that policy change. But it’s important to note that it is a policy change: this is not an effort to root out fraud, as Republicans have claimed, and bring people into compliance with an existing requirement.

With that detail established, now we can look at whether this policy change is an effective one.

After all, Republicans have packaged the proposal as a win-win-win. The low-income and disabled people who have long relied on Medicaid for health insurance but aren’t able to work continue to receive benefits. Can we clarify the following sentence? It has two buts. The beneficiaries who can work but currently don’t have to find jobs, but still receive insurance, either through Medicaid or through their work. Taxpayers save money as some of these individuals shift over to private insurance plans.

“No one will lose coverage as a result of this bill,” White House budget director Russell Vought pledged on Sunday.

But a version of the bill’s biggest change — a requirement that able-bodied, childless Medicaid recipients between the ages of 19 and 64 work, volunteer, go to school, or participate in job training for at least 80 hours a month — has already been implemented in some states, and the results haven’t been nearly as rosy as Republicans have promised.

When they’ve been tried in the past, work requirements often haven’t worked.

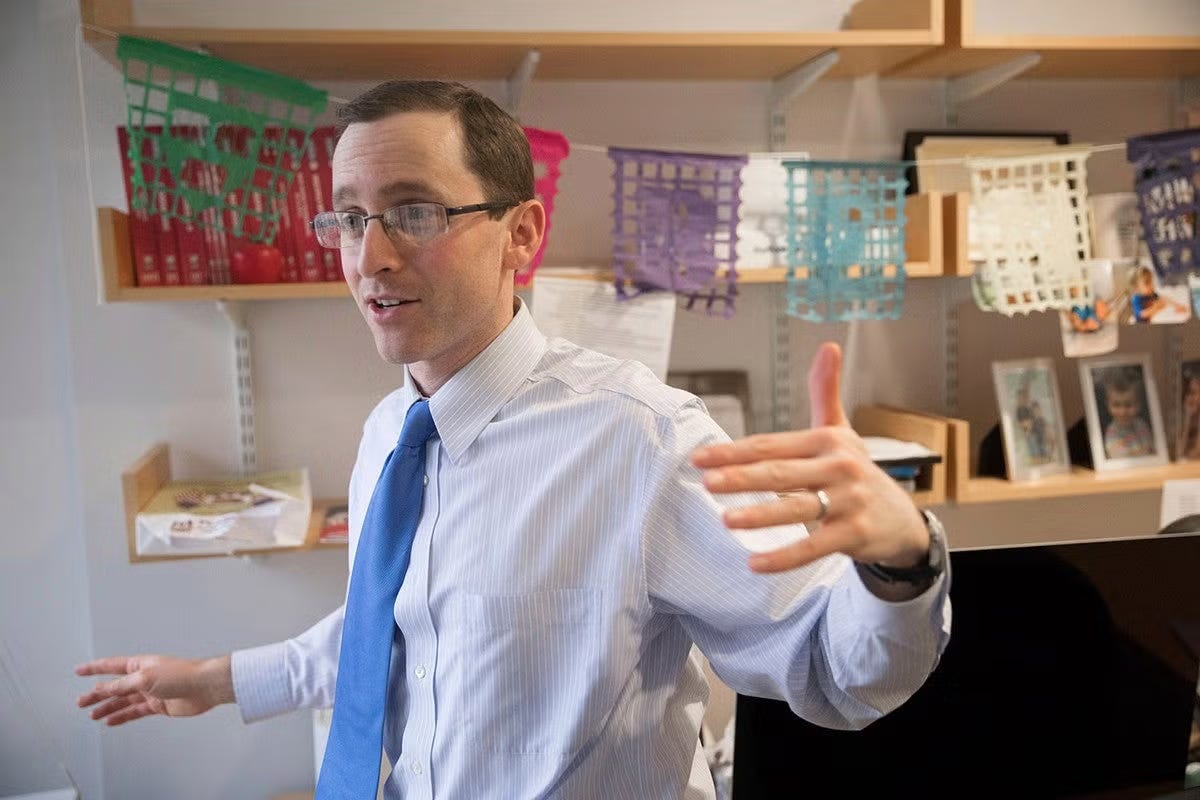

Ben Sommers is a Harvard professor who studies the intersection of health care and economics. He’s a double doctor — boasting an M.D. and a Ph.D. — and he’s considered one of the nation’s top authorities on Medicare and Medicaid.

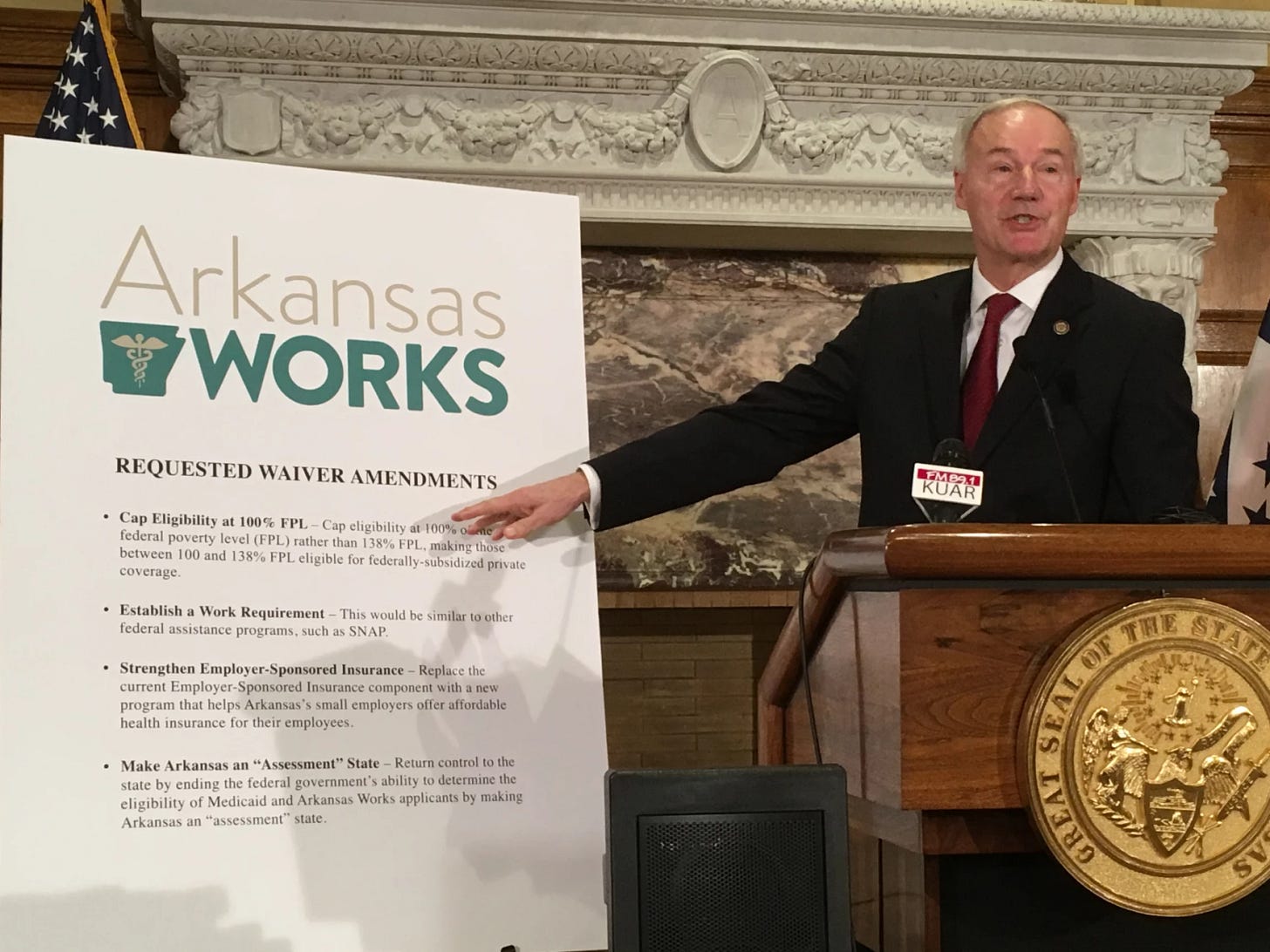

Back in 2019, after Arkansas implemented its own version of Medicaid work requirements, Sommers and four colleagues set out to study whether the statewide program had its intended effect: did it increase the number of low-income people who were working without reducing the share who were insured? (Sommers would go on to serve in the Biden administration, but the peer-reviewed study was conducted in his capacity as a Harvard professor, a role he’s since returned to.)

Their finding, Sommers told me in a recent interview: the Arkansas program was a “failed policy.”

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that among the age group to whom the requirements were applied, the share who were uninsured increased, from 10.5% to 14.5%, after the policy change. Meanwhile, the percentage who were employed decreased, from 42.4% to 38.9%.

The age bracket who faced the work requirements were no likelier to pick up jobs than other age groups. And they were much more likely to become uninsured, contrary to the promise that people wouldn’t lose their health care. “We saw big coverage losses without any improvement in employment,” Sommers said.

Why?

It turns out that most of the targeted Medicaid users were already meeting the eligibility requirements. And by “most,” I mean 97% of them.

“There just really wasn’t much room to move the needle, because almost everyone who could work already was doing so,” Sommers told me.

Similarly, across the country, there doesn’t appear to be a large universe of young men on Medicaid “playing video games all day” instead of working or caring for their family, as Johnson alleged. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 64% of Medicaid recipients under age 64 have jobs. Another 7% go to school. The next 10% can’t work because of illness or disability, and an added 12% don’t work because of caregiving responsibilities. That leaves only 8% of Medicaid recipients who aren’t working, attending school, taking care of relatives, or disabled or meeting the other requirements — and some of this group said they weren’t able to find work; Medicaid recipients are also disproportionately located in rural areas, where it might be difficult to access a job without sufficient transportation options.

From Ground News:

The House of Representatives narrowly passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, and now it’s with the Senate.

Depending on where you get your news, this could be seen as a necessary move to reduce federal spending or a dangerous blow to food and healthcare access for millions. With over 200 sources covering this story, Ground News is the most practical solution to exposing spin before we mistake it for fact.

If you like The Preamble, you’ll love their app and website. It gathers the world’s perspective on the most polarizing issues then breaks down each source’s bias and factuality.

Their Blindspot Feed is proof news isn’t just reported – narratives are crafted by partisan outlets we mistake as “unbiased.”

But Ground News is nonpartisan and independently funded by readers like us. And you get 40% off the same unlimited Vantage plan I use.

Subscribe now at ground.news/preamble for $5/month.

Johnson has said that people will lose Medicaid benefits under the Big Beautiful Bill only if “they choose to do so” by declining to work.

But that wasn’t the experience in Arkansas.

According to Sommers and his team, many of the Medicaid recipients who were covered by the work requirements in Arkansas — and who fulfilled them — didn’t know about the requirements, which meant they didn’t know how to report them and thus lost their coverage. Their survey found that nearly a third of adults in the target group hadn’t heard anything about the work requirements; nearly half weren’t sure if the work requirements applied to them.

This is a version of what Harvard’s Cass Sunstein has called “sludge” and what The Atlantic’s Annie Lowrey has called a “time tax”: the added burdens that prevent citizens — and usually those with the lowest incomes — from accessing government services they qualify for, by complicating the processes to receive them.

In the Arkansas case, Medicaid recipients had to report their compliance with the work requirements on an online portal that closed for several hours every night, making it difficult for people who worked full time — the outcome the policy was hoping to incentivize — to access it. Talk about “sludge.” (Not to mention that almost one-third of the recipients told Sommers’s team that they didn’t have internet access in the first place. And others didn’t speak English, erecting yet another barrier.)

“Essentially, there wasn’t really a problem to be solved," Sommers said. “Most of the people already were working or had a good reason not to. But because of the red tape that this created, many eligible people lost coverage.” What about the issue with people who live in rural areas where no jobs are available? One study I saw said this applies to around a million people.

Perhaps the most revealing part about the Arkansas experiment with work requirements is that Arkansas itself has acknowledged its shortcomings.

The state recently applied for a new waiver to impose work requirements, with some significant changes that it said “reflects lessons learned from the state’s efforts in 2018-2019.” Under its new proposal, the state government will increase contact with Medicaid recipients to spread awareness of the requirements. Instead of having to report their work hours monthly, the state will use existing data to see whether recipients are complying; those at risk of noncompliance will be matched with a “Success Coach” who will work with them to craft a personalized plan to get on track.

No more portal, no more late-night outages. And this time, the state will “ensure language translation services are available for all,” it said. Also, unlike the national plan, there will be no minimum number of hours recipients will have to work each month; just having a job will be enough.

The state’s new proposal even seemed to nod towards studies by Sommers and others. “Assessments of [the original program] showed that many people did not know whether they were subject to participation requirements and, if they were, what they needed to do monthly to demonstrate compliance,” the state admitted.

Medicaid is a program jointly administered between the federal government and the states; the pending Republican megabill wouldn’t give any guidance to states on how they should impose work requirements. In addition to adding a cost burden for states, that means many are likely to implement programs as strict as Arkansas’s initial effort (or stricter), leading to people losing insurance even if they fulfill the work requirements.

In total, according to the Congressional Budget Office, 7.8 million people who currently receive Medicaid are projected to lose benefits if the Republican package is enacted. If history is any guide (not just in Arkansas), many of the newly uninsured will likely be eligible for Medicaid, even with the new requirements, but will lose coverage because of reporting barriers.

When Sommers and his team went back to the Arkansans who had lost Medicaid coverage a year later, 50% said they were having problems paying off medical debt. 56% said they had put off receiving needed health care because of cost. 64% had delayed taking prescribed medications because they couldn’t afford them. And confusion still lingered: 70% of people didn’t know whether the policy was still in effect. (It wasn’t; a court had blocked it.)

“You can’t have it both ways,” Sommers said, noting that Republicans were simultaneously boasting about reducing Medicaid spending and insisting benefits would not be cut. “If there’s hundreds of billions of dollars of savings, it’s because you have removed people from the program. You’ve taken away benefits from people who are overwhelmingly eligible for it, based on all of the research.”

Sommers also noted that the nationwide impact of work requirements could be even more drastic than in Arkansas, which already had an unusual amount of data at its disposal on certain groups who were exempt from the requirements. Most states won’t have that, meaning even more recipients will have to self-report their eligibility. In the first draft of the GOP package, states were going to be given until January 2029 to plan for imposing work requirements. In the version that passed the House, that deadline was pushed up to December 2026, in response to demands from conservatives.

The 50 states are often referred to as America’s “laboratories of democracy,” a phrase coined by the late Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis.

“A single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country,” Brandeis wrote in a 1932 opinion.

In this case, several states tried a novel experiment. The federal government appears poised to ignore the results.

Governor Kemp in GA already tried this with the Pathways to Coverage work requirement program for Medicaid. It failed. It restricted healthcare access. I care for a unique population of kids with disabilities who largely utilize Medicaid.Even those with private insurance have Medicaid as secondary through our Katie Beckett program. Private insurance doesn’t cover home nursing or much of the DME equipment or medications these kids need, but Medicaid does. We don’t have long term care facilities in GA for kids, so unless your child is hospitalized there’s no respite. Many families have one parent who can’t work, because their job is providing 24/7 care to a child who needs help with all activities of daily living. God forbid you’re a single parent. Then you really struggle to work a paying job and care for the child. Constantly torn to be in 2 places at once. The poor and disabled are not the problem. The problem is all of us paying more in taxes than a big corporation when the corporations benefit from the cheap labor and (what used to be) stability and laws of this country. I strongly believe healthcare access should be a right and not a privilege. We need to do better. The system is terribly broken. Most of us working in it don’t have time to fix it, because we are trying to keep our head above water to care for our patients. To overhaul it would mean leaving clinical care and abandoning our patients, because there’s not enough time in a day to do both.

A bit on the Ga program: https://www.cbpp.org/blog/georgias-medicaid-experiment-is-the-latest-to-show-work-requirements-restrict-health-care

Ugh, America. It used to be the haves and the have-nots. Now we have three categories: the haves, the have-nots and the have-yachts and because the have-yachts need more, we must take away healthcare for millions of people. Gabe doesn’t even mention that with Republicans letting Obamacare subsidies expire, many more people who weren’t even on Medicaid will be unable to afford healthcare. In the richest country on the planet.