Could the US Ever Switch to Single-Payer Health Care?

America’s health care system is a maze of profit and paperwork. Some believe one payer could simplify it all.

It was a cool day in Ohio when Little John Cupp noticed that he had shortness of breath while pushing a shopping cart. During the fall months of 2021, more symptoms started popping up, including severe swelling in his feet and ankles and an inability to sleep unless he was sitting up. A doctor found the culprit: Cupp’s heart was struggling to pump blood.

Cupp’s doctor recommended that they insert a catheter to see whether Cupp’s arteries were blocked. In order to get the procedure, Cupp needed prior authorization from his health insurance company. Cupp’s doctor sent the request to UnitedHealthcare, but days later, Cupp got a denial letter, which said the procedure had been deemed “not medically necessary.” The denial was issued by a company called EviCore by Evernorth, which uses an AI-generated algorithm to approve or deny prior authorizations.

His doctor tried and failed again to get approval. Cupp was later approved for a different exam, but three months after his first denial, Cupp suffered a fatal cardiac arrest. An expert told ProPublica that his life might have been saved if he had received the heart catheterization when it was first ordered.

In the US, private insurance companies, for-profit and nonprofit health care providers, and government-run programs all get a say in what patients can and cannot do — in Cupp’s case, the provider and the insurance company disagreed, and Cupp lost out on potentially life-saving care. His tragic story is just one example of how our mixed health care system, where both the public and private sector provide health care services, is riddled with obstacles that delay or prevent patient care.

“When you have a mosaic or a patchwork system, some people who are at the edges of the patches are going to fall through the cracks,” said Dr. Atul Gupta, an assistant professor of health care management at the University of Pennsylvania, to The Preamble.

Some people see an answer to this problem: overhaul our current system and create single-payer health care, in which the government pays for medical services with taxes collected from citizens.

Our current system

The current mosaic of health care started during World War II. Wages were frozen, so employers began offering health insurance as a benefit to attract workers because it didn’t count as earnings. In the 1950s, thanks to tax deductions for employer-sponsored health insurance, more companies began offering coverage. The government got directly involved the next decade with the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid. Rising health care costs spurred the creation of managed care systems, a type of insurance that costs less but restricts your options when it comes to doctors or facilities. The Affordable Care Act expanded the government-run Medicaid, created a marketplace of insurance plans, and included a mandate that most Americans have some form of health insurance.

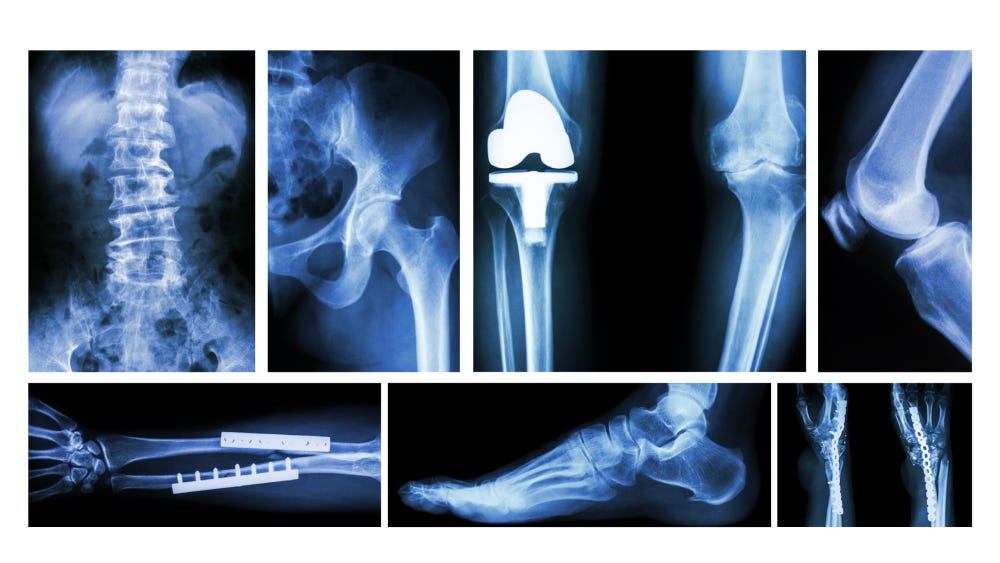

A crucial piece of our system is how prices are negotiated. A patient who needs a total knee replacement will sometimes face a cost of $15,000, while others are charged $75,000. That $60,000 spread exists because insurance companies negotiate directly with health care systems and set rates for medical services.

The providers that participate in these negotiations and agree to take your plan’s contracted rate are labeled as “in-network.” If you go with out-of-network providers instead, your copay, deductible, or coinsurance is likely to be higher, or your insurance won’t cover it at all, forcing you to foot the whole bill. (Copays are a fixed, pre-determined price you pay for a service, like an office visit. Your deductible is how much you pay for services before your insurance kicks in, and coinsurance is when you split the cost of the service with your insurance company.)

After the negotiated rate is set for each hospital and clinic, the insurance company decides how much of that amount it will pay and how much the patient owes. If Insurer A has negotiated with Hospital A that a total knee replacement will cost $60,000, the insurance company might decide to cover half of it. The other half would then be owed by the patient, whether that’s entirely out of their pocket or through copays, deductibles, and coinsurance.

Prior authorization, what Little John Cupp needed for his heart catheterization, also makes its way to the negotiating table. Insurance companies want to save money, so they often demand the right to give approval in advance for expensive procedures or medications. They might, for example, require patients to seek prior authorization for a surgery or a costly name-brand drug. Insurers say this helps prevent patients from going through unnecessary procedures and limits fraud.

The result of all this is a complex system in which prices can seem arbitrary.

“What we’re seeing today is different payers paying different prices for health care services only because they’re a different payer, which makes no rational sense to have people pay for the exact same services but pay different prices,” said Dr. Jennifer Schultz, co-director of the health care management program at the University of Minnesota Duluth.

A single-payer model

Health care costs continue to rise, leaving more people unable to pay.

The average annual premium for a family with workplace insurance reached nearly $27,000 in 2025. But it’s only going to get more expensive because Affordable Care Act premium tax credits are set to expire at the end of the year. Those credits helped offset participant insurance premiums. The expiration of these credits is predicted to cause an average increase of about 114% in what Marketplace (HealthCare.gov) enrollees pay. Separately, insurance companies are also expected to increase how much they charge by 26%.

Dr. Schultz said people cannot sustain paying these rising prices year after year. “Something has to happen,” she said. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that 10 million people will become uninsured due to Medicaid and ACA marketplace cuts in the law. If anything close to that happens, more Americans than ever might start to favor the alternative of single-payer health care.

Dr. Georges C. Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, explained to The Preamble that Medicare could be the foundation of a single-payer system, “What you would do,” he said, “is that every year or two you would bring down the eligibility for [Medicare] until everybody was in it. It gives people time to adjust. It gives the private sector time to adjust.”

A 2022 study by Yale researchers showed that a single-payer health care system would save about $438 billion in overall health care spending per year. They wrote that a system like Medicare for All “would reduce costs by improving access to preventive care, reducing administrative overhead, and empowering Medicare to negotiate prices.” The study also says single-payer care would “eliminate pricey insurance premiums and reduce fraud.”

While there are multiple models on which a single-payer system could be structured, Dr. Gupta suggests a solution in which everyone gets basic coverage, including things like emergency care and basic preventive care, from birth to death. This would address many issues, including inconsistent costs across providers and fear over emergency medical bills. A fee schedule would set how much providers are paid for certain services, and the rates would be reviewed periodically.

“That at least solves this issue of, well, if I get really sick, what’s gonna happen?” Dr. Gupta said. “No matter where you are, what stage you are in life, as long as some basic kind of health care is guaranteed to you, it really doesn’t matter if you transition, if you’re between jobs for a little bit of time.”

Dr. Schultz said that in a single-payer system, there should be a “price ceiling that they can’t go above. It’s called reference-based pricing. We would reference prices based on what traditional Medicare pays, and use those prices. And if folks wanted to go to a different specialist that charged a higher price, they would have to pay the difference. But we would at least have providers in the network that accept that reference based price.”

She also said a single-payer system could help people get the health care they need without being scared off by high copays and premiums. “Under single-payer, when you get everybody in the same pool and you spread out the cost of health care and you control prices, we can definitely get lower premiums than what we see today,” Dr. Schultz said.

The pitfalls

But some critics of a single payer system worry that their taxes will go up. This is likely true — in order for the government to cover health care costs, they would need to raise taxes. But some proponents argue that health care costs and insurance premiums per person or family would in turn go down, which means that people would ultimately end up saving money.

One analysis of New York state found that “as payments for health care shift from premiums and out-of-pocket payments to progressive taxes, most households in New York could pay less and the highest-income households could pay substantially more.”

Another major concern is that wait times would surge because health care would be free for everyone, and the availability of some services would be restricted because providers would be overloaded. There’s nothing to show that this isn’t true, and the problem could be exacerbated by the ongoing physician and nursing shortage in the US. Patients already suffer from long wait times, with the average person waiting 31 days to get a primary care appointment. This shortage of primary care physicians is expected to grow to 40,400 doctors by 2036. Figuring out how to address this shortage and wait times would need to be a part of building a single-payer system.

A single-payer system would set prices, and therefore other critics argue it would stifle innovation as price caps on drugs would mean less revenue for companies that then couldn’t fund new research and projects. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America warned in 2021 that government price controls could eliminate the incentive for companies to invest in the development of new medicines, both in the US and abroad.

But proponents of single-payer systems argue that single-payer systems would reduce high administrative costs in the private sector, which would free up money for research and development even if price controls limit revenue. They also argue that the federal government already funds initial research and development for new drugs. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), for instance, puts $48 billion annually into medical research. However, this number does not factor in the recently enacted slashes to their budget, estimated at more than 40%. In 2024, drugmakers poured about $288 billion into R&D. Figuring out how to incentivize R&D would need to be a priority of those building the single-payer system.

The political will and desire

A single-payer health care system might not have been able to save Little John Cupp, but it could have taken down some of the roadblocks he faced to accessing care.

“It’s going to require political will and desire. There was a time when there was no question, both parties and independents believed that everybody had the right to care,” Dr. Benjamin said. “What’s happening right now is we’re having a national debate about whether or not people have the right to health care. That’s the wrong argument. Health care is a fundamental human right. We need to accept that.”

Coming from a country where going to the doctor is no big deal American healthcare was a hell of a shock for us. We were (are) both still fairly healthy and I was lucky enough to be on my husband’s work insurance plan but co pays for every visit mean budgeting for a simple Dr visit is off putting and I wonder how many small issues could be caught early and sorted out before they became bigger and more pressing sometimes life threatening issues. Prevention should be part of healthcare, the US is the only country in the world where having a heart attack can bankrupt you. The language used in U.S. healthcare is deliberately confusing (especially for seniors - Medicare advantage should have a dis in front of it) The heartbreaking thing is that the care and innovation in treating patients is top notch but the price for that care is way too high.

Let me give you an example of single payer care. A friend was traveling to Edinburgh with her family and as they boarded the plane her sister slipped and fell hurting her leg. She made it onto the plane arrived in Scotland in immense pain and went from the plane straight into hospital - she had fractured a bone in her leg. The hospital set the bone, kept her in at least two nights and discharged her with a pair of NHS crutches. So no insurance, not a U.K resident. Her bill? About 150 pounds. We are the richest country in the world but we’re the only one who ties healthcare to employment and who doesn’t have single payer.

This was so informative. I hope we get to single payer healthcare without it taking many suffering to realize it’s needed 😕 I do also think the language used by politicians may help their messaging! Single-payer healthcare for some reason sounds like something my parents would get behind, whereas they will never like the phrase “Medicare for all”. And maybe that’s on them.