Congress? Never Heard of It

Tyrants make laws. That’s why the Framers built a Constitution to stop them. Article I strikes like a hammer: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” All.

James Madison, writing in Federalist No. 47 in 1788, warned that the “accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands… may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.” In Federalist No. 73, Alexander Hamilton calls the veto “a shield to the executive” because he saw it as a defensive safeguard: the president’s way to protect his office (and, by extension, the people) against rash, unjust, or unconstitutional laws passed by Congress. The veto was not intended as a power to originate policy or to let the president write laws by blocking them for political reasons — Congress remained the body meant to legislate.

The Revolution was proof enough. The Declaration of Independence devotes its longest section to George III’s abuses: imposing taxes without consent, creating offices to harass colonists, dissolving legislatures at will. Parliament existed, but royal prerogative reigned. Americans swore never again to live under a ruler whose word was law.

Presidents have always tested that boundary. In 1832, Andrew Jackson vetoed Congress’s recharter of the Bank of the United States simply because he despised it. His enemies caricatured him as “King Andrew I,” enthroned in robe and crown.

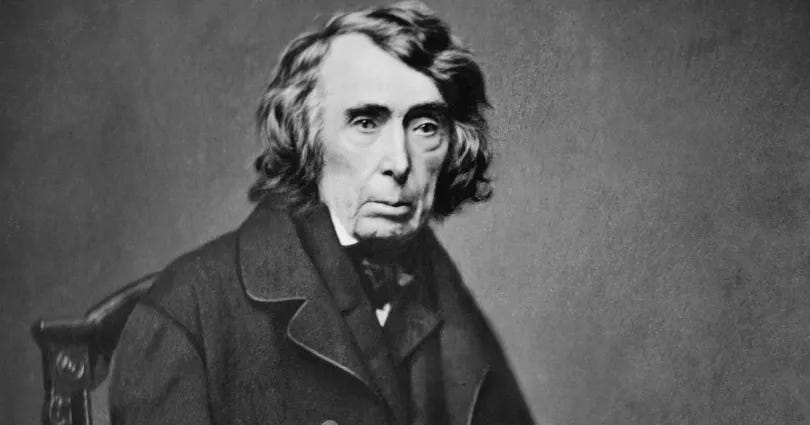

Even at the peak of national emergency, presidents could stretch enforcement, but they could not legislate. In 1861, Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus without congressional approval; Chief Justice Roger Taney, in Ex parte Merryman, ruled that only Congress could suspend the writ. In the 1930s and ’40s, Franklin Roosevelt signed thousands of executive orders, but the Social Security Act (1935), the Securities Exchange Act (1934), and the National Labor Relations Act (1935) all came from Congress.

And yet President Donald Trump makes claims to legislative power the Constitution does not grant. “We’re just gonna do it,” he scoffed when the point was raised that only Congress could change the name of the Department of Defense to the Department of War.

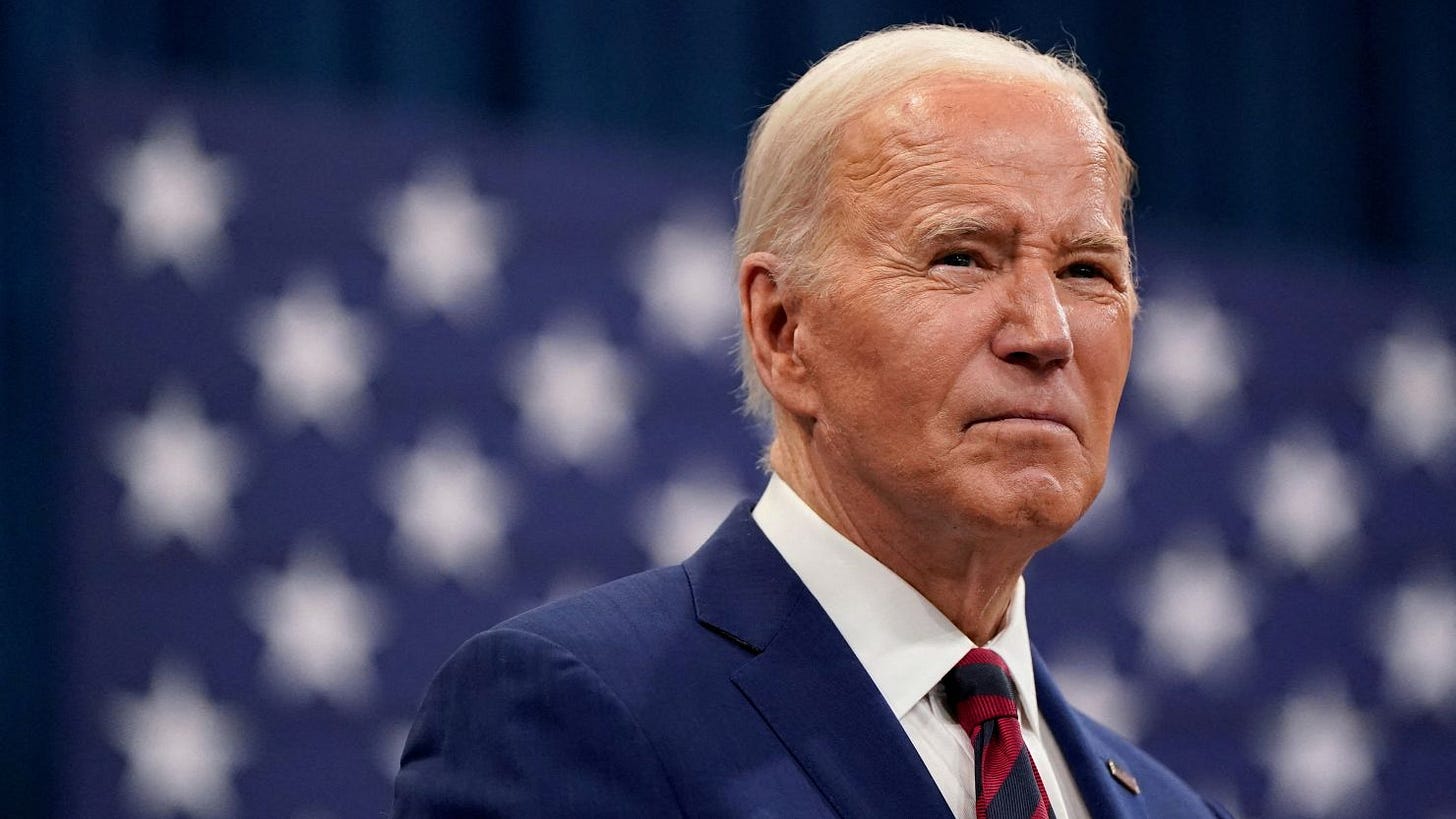

Courts have rebuked presidents for executive overreach before. The Supreme Court recently struck down President Joe Biden’s student-loan forgiveness plan as an unlawful use of administrative power. But that episode, while significant, still presumed Congress held the legislative keys. Trump’s posture is different: he doesn’t test the edges of executive authority, he collapses the distinction between the branches altogether, treating legislation itself as a presidential prerogative.

Trump’s actions match the words. In March 2025, his allies introduced the Dismantling Government Act (H.R. 1295), which would allow him to abolish entire agencies unilaterally. Imagine the Department of Education erased overnight because one man chose to — a man who never served in Congress.

And even without such a law, he has pursued the same end through attrition; he’s defunded programs, withheld appropriations, and instructed administrators to dismantle their own agencies from within. Where Hamilton imagined the executive executing, Trump imagines the executive extinguishing.

In February 2025, Trump signed Executive Order 14215, compelling agencies — including those Congress deliberately insulated, like the FCC and SEC — to accept his reading of the law as the only “authoritative” one. Legal allies seemed to spelled it out: “Trump is the law for the executive branch.” Congress may pass legislation, but under this doctrine, Trump alone decides its meaning. No president had done this before. Independent agencies had always been expected to exercise their own legal judgment, subject to review by Congress or the courts. Trump replaced that tradition with something new: not influence, but command.

And the pattern widens. His administration has sought to strip federal workers of appeal rights after they were fired, leaned on judges who ruled against him, and threatened law firms that challenged him. “IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I’M COMING AFTER YOU,” he wrote on social media in 2023, and he certainly seems to be making good on the threat. Each act is rehearsal for the main event: a presidency that not only enforces law but punishes anyone who says, You cannot write it yourself.

The contrast is brutal. Washington issued eight executive orders. Trump is attempting to crown himself with a legal pad. The Framers did not draft parchment to sanctify that. They fought a war to bury it.

If October 2025 ends with Americans letting a president steal Congress’s pen, they will not be living in a republic. They will be wandering a wax museum version of one, admiring the lifelike figures, blind to the fact that the whole thing is melting.

Alexis Coe, a presidential historian, writes the Substack Study Marry Kill. She is a history columnist for The New York Times Book Review, a senior fellow at New America, and the bestselling author, most recently, of You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington.

Alexis, thank you! Your last paragraph is powerful:

“If October 2025 ends with Americans letting a president steal Congress’s pen, they will not be living in a republic. They will be wandering a wax museum version of one, admiring the lifelike figures, blind to the fact that the whole thing is melting.”