Congress Is Gambling with the Cost of Your Health Care

Most controversial political programs tend to follow a familiar trajectory.

A policy is instituted by the party in power, while the opposition party kicks and screams and complains. It remains a political hot button, at least for a while. But then, over time, the American people become used to it. They grow to expect it. The other party accepts that they’ve lost the battle. Eventually, the policy becomes a standard part of American life, the new baseline that both parties operate off of going forward, without trying to double back and get rid of it.

That’s what happened with Medicare, which conservatives like Ronald Reagan bashed as “socialized medicine” in the 1960s. Decades later, Republicans have given up running against Medicare: in fact, Donald Trump was elected in 2024 promising he wouldn’t touch the program.

The same is true for many of Trump’s 2017 tax cuts. Sure, Democrats didn’t vote to extend them as part of the Big Beautiful Bill earlier this year, but they also had four years under Joe Biden when they could have repealed the changes to the tax code. They didn’t. In 2024, Kamala Harris signaled that she would keep the Trump-era tax cuts in place for people making under $400,000 a year. Voters grew accustomed to their new tax rates; Democrats knew better than to mess with that.

It’s possible that the Affordable Care Act is now undergoing this dynamic. Obamacare, as the law is known, was incredibly controversial when it was first passed by Democrats in 2010. Republicans pledged for the next several election cycles to repeal the health care package: in 2017, that was the first major legislative effort of Trump’s first term. But, not even a decade later, you don’t hear many Republicans talking about ending Obamacare anymore, and Trump certainly hasn’t mounted a renewed repeal push in his second term. The program went from polarizing to broadly popular. After years of fragility, it’s almost certainly here to stay.

One test of the extent to which Obamacare remains a partisan football will come in the next few months, as lawmakers debate whether to extend an addition to the law that Democrats tacked on under Biden.

The original 2010 law created tax credits to help subsidize the cost of monthly health insurance premiums for coverage purchased through the Obamacare exchanges. The tax credit is refundable, which means it is available to someone even if their income isn’t large enough to pay federal income taxes. Its size varies per recipient: the average premium tax credit is $550 per month (out of an average monthly premium cost of $619 per month for Obamacare plans).

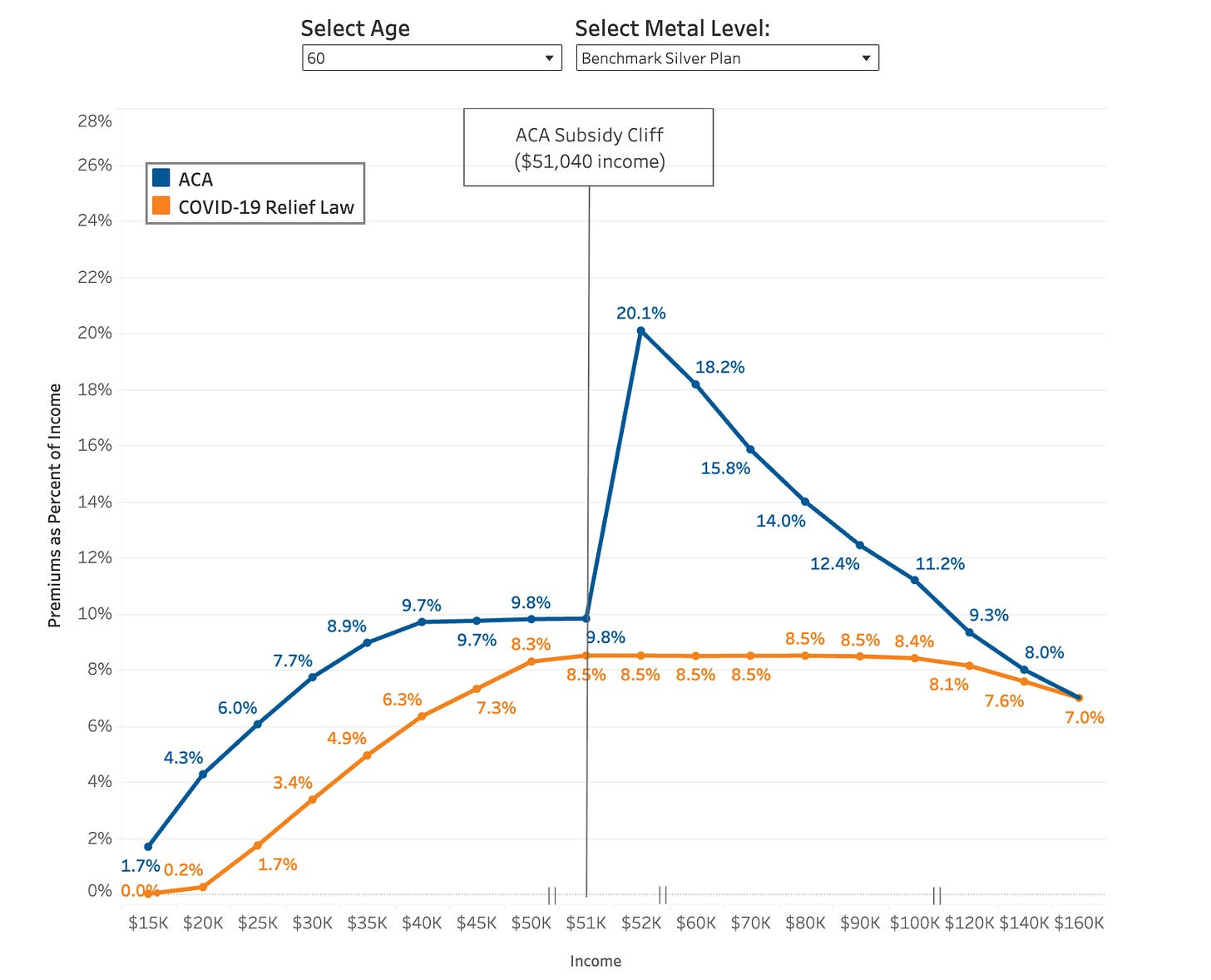

At first, the benefit was available to those whose incomes were between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level. (Currently, for a single individual, that would be anyone whose income is between $15,650 and $62,200. For a family of four, that would be a household income between $32,150 and $128,600.)

In the Biden-era Covid-relief law (the American Rescue Plan Act), Democrats removed that upper cap for 2021 and 2022, changing it so that anyone was eligible for the tax credit as long as their income was above the federal poverty level and their premium cost them at least 8.5% of their household income. The tax credits were also expanded, which almost completely eliminated premium costs for anyone who made up to 150% of the federal poverty level ($23,475 for a single individual). In the Inflation Reduction Act, Democrats extended these changes for three more years, setting an expiration date of December 31, 2025.

If the enhanced tax credits aren’t extended again, many Americans will see their health care costs shoot up. According to KFF, a nonpartisan health care research group, out-of-pocket premium costs for the average American who buys insurance through the Obamacare exchanges would skyrocket by 75%. Per the Congressional Budget Office, 4.2 million people are expected to be priced out of coverage and become uninsured.

“If Congress fails to act, premiums could jump overnight by hundreds or even thousands of dollars, especially in rural counties where fewer insurers compete,” Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, who oversaw Medicare, Medicaid, and Obamacare under Biden, told The Preamble. “In [states that use the federal Obamacare exchange], costs are projected to rise an average of 93% for families losing eligibility. Combined with new rules that make enrollment harder, the result will be fewer healthy people in the market, higher premiums for everyone else, and millions at risk of losing coverage altogether.”

Before the Biden-era changes, the tax credit’s income cap created something known as the “subsidy cliff,” whereby premiums would shoot up right after someone exceeded the 400%-of-the-poverty-line threshold. The enhanced subsidies flattened that cliff — but a failure to renew them would introduce it once again.

Not too long ago, in the days of Republicans calling for Obamacare repeal, it would have been laughable to think that the GOP might take part in extending a benefit tied to the signature Democratic program. But, now, the enhanced premium tax credit has become the norm for many Americans; such a large increase in health care costs would cause a massive jolt. With that political reality in mind, some Republicans are nudging their leaders to drop the party’s longstanding opposition to Obamacare.

Last week, Rep. Jen Kiggans (R-VA) introduced the Bipartisan Premium Tax Credit Extension Act, which would keep the enhanced tax credits in place for one more year, pushing the deadline to the end of 2026.

So far, the measure has attracted 16 cosponsors: 11 Republicans and five Democrats. Strikingly, the group features some of the most vulnerable members of the House, a signal of where lawmakers in tough races want to be on this issue ahead of the 2026 midterms. The bill’s supporters include Republican Reps. Rob Bresnahan (PA) and Juan Ciscomani (AZ), who won their seats by 1.6 and 2.5 percentage points in 2024, respectively, and Democratic Reps. Jared Golden (ME) and Don Davis (NC), who won reelection by 0.7 and 1.7 percentage points, respectively.

Republican congressional leaders haven’t said whether they will back Kiggans’s effort, although they haven’t shut the door on it either.

“Well, the Democrats created this problem by putting the deadline or the phase-outs in the legislation they acted on earlier and by dramatically expanding the size of the program in the first place,” Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) said at a press conference last week. “So I hope they will come to us with a suggestion and a solution about how to address it. But obviously it’s something that some of our members are paying attention to.”

“I don’t love the policy,” House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) said in a recent interview, while adding that he understands the “the political realities and the realities of people on the ground.”

“I don’t think we should be subsidizing high-income earners,” Johnson continued. “It was a Covid-era issue, and so that’d be a big thing for the Republican Party to continue or advance that. At the same time, we don’t want anyone to be adversely affected by that.”

Johnson’s comments represent the bind now faced by Republicans: they may oppose the underlying policy, but do they oppose it enough to risk people facing adverse consequences on their watch?

The premium tax credits could end up being part of a bipartisan deal to stave off a government shutdown. With government funding due to expire at the end of the month, Republicans could offer Democrats an extension of the enhanced subsidies in exchange for supporting a “continuing resolution” to avert a shutdown. Some left-of-center pundits, like Matthew Yglesias, have called for Democrats to oppose any funding bill that doesn’t include the expanded tax credits.

In addition to creating a fascinating political dynamic — 12 years after Republicans shut the government down over Obamacare, a shutdown could now be avoided due to the same law — the enhanced Obamacare subsidies shine a light on how Washington handles policy, shuttling from deadline to deadline.

Political parties will often set new programs to sunset after a few years to make pieces of legislation look like they cost less, even if their plan was to make the policy permanent all along. The Inflation Reduction Act, for example, was said to have reduced the deficit — but that is partially because the enhanced subsidies were scheduled to last only through this year, even though Democrats are now working to extend them. If they are successful, the price tag of the 2022 bill will arguably end up being larger than it first appeared.

These accounting tricks help explain why policies in Washington so frequently expire and why lawmakers are always rushing to renew them. The author of every policy hopes that their program will become so relied on that Congress has no choice but to re-up it. Lawmakers are currently debating whether a key plank of the Obamacare ecosystem has achieved such staying power; the cost of health care for millions hangs in the balance as they do.

The Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson: “I don’t think we should be subsidizing high-income earners.” What a laugher. Take the contraction “don’t” out of that statement and you pretty much have the Republican Party platform in a nutshell.

Thank you so much for addressing this! I’m a health insurance agent, and the anxiety going into this open enrollment has been high. One of the largest carriers in my state recently mentioned that they’d expect only 60-70% of current members to renew. That would mean 30-40% loss of income for me and my family as well.

It’s such a tough line to walk when your career hinges on helping others. I truly love being able to help and find solutions to make it work for people, but the lowest income earners already saw their premiums double this year in my state. The IRS allowed premium cost to increase from 2% of income to 4% in 2025, and many of my most vulnerable clients were impacted. I don’t see how they could expect to afford it to double again. 🥺

Also the vast majority of the higher income earners that receive significant subsidies are retirees waiting to get on Medicare. Without subsidies, the lowest plan premiums start close to $1000 a month per person for that age range. The closer you get to Medicare age (65), the more it costs. Thank you for addressing it because so many people don’t understand how hard this could hit them! Not to mention the proposed changes to repayment of the tax credit. That’s a whole other scary issue for people whose income is hard to predict.