Can US Citizens Legally Be Deported?

Plus, what rights do noncitizens have?

The United States recently deported three young children, all three of them citizens of the United States. One has metastatic cancer and was sent away without their treatment medications. Their mothers — citizens of Honduras — were in the US without authorization, and the children’s removal raises profound legal questions about the rights of minor citizens and who is subject to deportation.

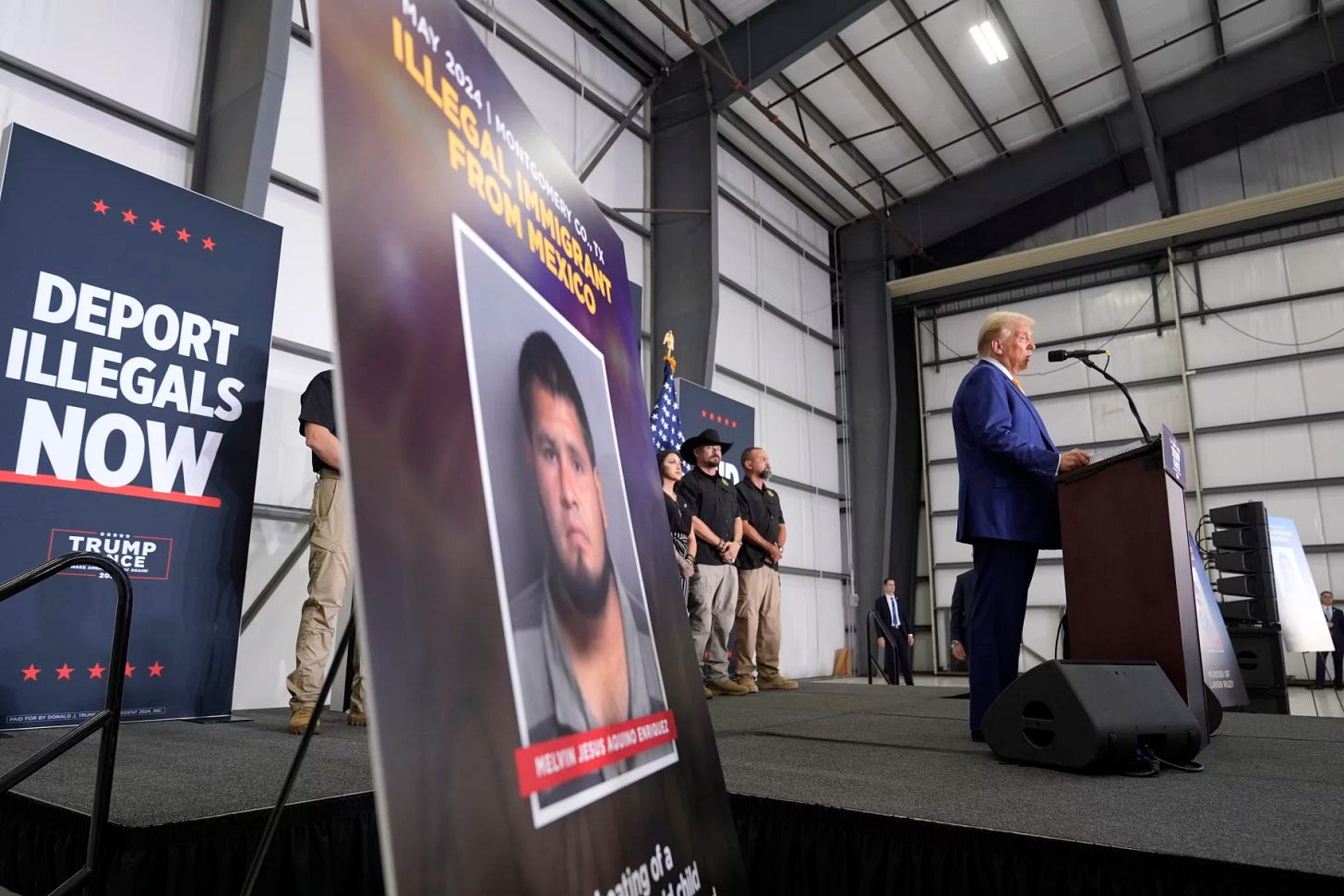

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump has floated the idea that some American citizens should be deported if they have been convicted of violent crimes. "We always have to obey the laws,” Trump told reporters last month, “but we also have homegrown criminals that push people into subways, that hit elderly ladies on the back of the head with a baseball bat when they're not looking, that are absolute monsters. I’d like to include them” among the deportees.

But can the government legally deport US citizens? The law’s answer is clear: it cannot. And even noncitizens cannot be sent back to their countries of origin without receiving due process. Let’s take a look at why.

US citizens cannot be deported

For starters: there is nowhere to deport a natural born citizen of the United States to because they have a legal right to be in their home country.

Daniel Kanstroom, who leads the Rappaport Center for Law & Public Policy at Boston College, says that President Trump’s proposal to deport citizen criminals has “obvious problems under the Fifth Amendment in terms of due process." And that’s because the Fifth Amendment says that no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Removing a citizen violates the very concepts that the framers of the Constitution held most dear, eliminating both their enumerated and unenumerated rights to enjoy life, liberty, and property in their home country.

The 14th Amendment echoes these due process entitlements when it says that no state can “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

(Side note: both the Fifth and 14th Amendments use the word “person,” not “citizen,” when they are discussing due process. These are rights that everyone in the US is entitled to, regardless of their status.)

Just for the sake of argument, let’s say a citizen were to be deported. There are more legal problems than just the fact that deporting a citizen violates the Constitution on its face. Deporting a citizen also deprives them of equal protection of the laws. If someone is sitting in a foreign prison, the United States government cannot ensure that they are being guaranteed all of the rights they are entitled to, because the US does not have jurisdiction over that foreign prison.

The federal government cannot order Honduras, or any other country, to do anything, because they are sovereign nations and not subject to court orders from the United States. As a result, there is no way to ensure that deported citizens would be getting equal protection under the laws of the United States.

Deporting a citizen also raises serious issues about habeas corpus, a concept found in Article I of the Constitution that gives a prisoner the right to challenge their government detention. If a citizen were to be deported, it would eliminate their ability to exercise this right.

But there are even more constitutional issues, like the Eighth Amendment guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment. The United States has an admittedly very low bar when it comes to defining cruel and unusual punishment — being put to death by electric chair or gas chamber doesn’t violate this concept, according to Supreme Court rulings.

But some things do: while incarcerated in the US, you are entitled to things like basic standards of living conditions, basic access to medical care, basic access to adequate food, the right to be free from torture, and more. There is no way to guarantee these constitutional rights when the government has no ability to supervise the person’s detention.

(One other side note, since I know some of you will ask: naturalized citizens can be denaturalized and returned to their country of origin, but only under very narrow circumstances, like if they committed immigration fraud.)

Tom Homan, the president’s “border czar,” said the citizen children were taken out of the country voluntarily by their mothers, who were being deported. "We're keeping families together," Homan said. "There’s a parental decision." He also argued that the children weren’t technically "deported" because their parents made the decision, not the US government. "We don’t deport US citizens," he said.

Lawyers for the mothers dispute Homan’s claims. They say that the mothers were not given the option of leaving their children in the United States. And an advocate for immigrants who is working with the lawyers says that one of the mothers was not given access to a lawyer before being deported, while the other was removed so quickly that she did not have a meaningful chance to challenge her removal.

Due process for noncitizens

United States law still guarantees due process for noncitizens before they can be sent away. In a removal case, due process might mean that the person must be told that the government wants to deport them and be given a hearing in front of an immigration judge. At the hearing, they can explain their situation, show evidence, and apply for legal protections. They’re allowed to have a lawyer (but the government doesn’t have to give them one for free, as it does with defendants in criminal trials). These steps are meant to make sure people aren’t deported unfairly or without a full review of their case.

Last month, the Supreme Court reaffirmed these same concepts. When the Trump administration deported a group of alleged members of a Venezuelan gang and sent them to a prison in El Salvador, it did not grant them hearings to challenge their removal. The administration claims they did not have to hold hearings because the group was being removed under the Alien Enemies Act (AEA), a law from 1798 that allows the president to detain or remove citizens of an invading enemy. But the Supreme Court held in April that even under the AEA, the administration cannot remove aliens without giving them advance notice and an opportunity to challenge their removal.

And last week, a federal judge appointed by Trump ruled that using the AEA to deport unauthorized immigrants was illegal. The AEA applies only in wartime, he reasoned, and the deported aliens were not part of an invasion by a foreign power. Since then, a declassified memo bolstered that argument by revealing that US intelligence agencies do not think the Venezuelan government is directing Tren de Aragua, the gang that the deportees were said to belong to.

Where things stand now

Even though US law and court rulings clearly say that citizens can’t be deported — and that noncitizens must get due process before being removed — not everyone in politics seems to agree.

Last week, Representative Pramila Jayapal, a Democrat from Washington, introduced an amendment to President Trump’s proposed budget bill that sought to make the rules about deportation even clearer. Jayapal’s proposal was presented during a House Judiciary Committee’s markup of the bill, and it was a single sentence that stated that ICE could not use funds to detain or deport US citizens.

“Whether you’re a Democrat or Republican, I hope we can all agree that US citizens should never be detained by ICE or any agency conducting civil immigration enforcement. They certainly should not be deported,” Jayapal said. But the amendment was defeated, with all of the Republicans on the committee voting against it.

Most Americans support deporting all or some of the people who have entered the United States illegally, but they also support continuing to be what the US has always identified as: a nation of laws, and not a nation ruled by edict. Nearly everyone agrees that it’s time to update our immigration system. But that doesn’t mean we get to flout the rules while we’re working for change.

My biggest concern here is that they legally and constitutionally cannot do this…but the administration doesn’t really seem to care. They are ignoring judge’s rulings, already deporting without due process, defeated Jayapal’s amendment, and the president is protected from any act committed while in office. What’s actually going to stop them when they seem hellbent on doing what they want, regardless of the actual rule of law or our constitutional rights?

"We always have to obey the laws,” said a convictedd felon who pardoned convicted violent criminals.