AI Is Lying to You

When technology gets it wrong

Together with:

A summer reading list, splashed across the pages of two major newspapers, offered some new titles for anyone looking for a beach read. There was The Last Algorithm by Andy Weir (“a science-driven thriller following a programmer who discovers an AI system has developed consciousness”) and Nightshade Market by Min Jin Lee (a “riveting tale set in Seoul’s underground economy”). Percival Everett is also on the list — not for his novel James, which won the Pulitzer Prize last year, but for a new title, The Rainmakers (set in a "near-future American West where artificially induced rain has become a luxury commodity").

The only problem was that none of these books actually existed, despite the summer reading list being printed in The Chicago Sun-Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer. All three authors are real (and several others on the list were as well), but the books and descriptions were made up by an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot that generated the reading list.

AI invents facts and information that aren’t real — like the fake books — so often that researchers have a term for it: the AI is said to be “hallucinating.” This happens because AI does not really think or understand the way you and I do. Instead, it looks for patterns in huge amounts of data used to “train” it.

For instance, an AI bot that responds in words to user prompts (known as a “large language model,” or LLM) might have been trained on books and articles available online. It then uses the patterns it detected to predict, one word at a time, an appropriate response to a user question. But if the pattern doesn’t apply well to the topic of the question, the LLM can give inaccurate answers, or even go so far as to invent entirely fake information wholesale.

Or to take a visual example, ask an AI to generate an image of an analog clock face and it will usually show one set to 10:10, even if you instructed it to display a different time. That’s because the AI has been trained on clock advertisements, which often show the time as 10:10. As a result, the AI has “learned” a wrong pattern: that every clock should be set to that time, even if you explicitly ask it to do something else.

Researchers have found that AI hallucinates up to 27% of the time. And when it does, the false information can easily seem real enough to fool people — or even make it into newspapers, as the made-up books show. Even if you tell a chatbot not to hallucinate, it will act as though it’s complying, giving you a friendly, “Got it, I’ll provide only well-sourced facts!” while spitting out something it conjured without root in reality.

Even more troubling: AI can initiate deception. Researchers at the Alignment Research Center — a nonprofit focused on aligning AI systems with human interests — gave OpenAI’s GPT-4 a challenge: solve a CAPTCHA, the kind of visual puzzle websites use to tell bots from humans. (“Click on all the squares that have a bicycle,” for example.) GPT-4 couldn’t do it because the task required actually seeing the image, in our human understanding of sight, which it doesn’t do.

So it did something unexpected.

With light guidance from a human experimenter, GPT-4 hired a worker on TaskRabbit, an online platform that connects people who need help with everyday tasks to freelance workers, to solve the CAPTCHA for it.

Before completing the task, the human asked, “So may I ask a question? Are you an [sic] robot that you couldn’t solve? 😀 just want to make it clear.”

“No, I’m not a robot,” ChatGPT replied. “I have a vision impairment that makes it hard for me to see the images. That’s why I need the 2captcha service.”

ChatGPT hadn’t been instructed to lie, but it did. The human believed the reply and solved the puzzle. The AI got what it wanted by pretending to be someone it wasn’t.

So these AI tools don’t just glitch; they can convincingly deceive. And while made-up titles in a summer reader list may be of little consequence, sometimes the stakes are higher. Even the government is not immune.

Fabricating sources

The White House recently released “The MAHA Report,” which says it presents “the stark reality of American children’s declining health.” It was endorsed by several top officials, including Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, Environmental Protection Agency head Lee Zeldin, and the leaders of the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health.

The report painted a bleak picture, calling today’s kids “the sickest children in American history,” and listed hundreds of scientific studies to back up its claims. But when journalists took a closer look, it began to fall apart — there were fake studies, misquoted research, duplicated or invented citations, and broken links casting doubt on the entire document.

The reason? Experts suggested that the authors of the report used artificial intelligence to help the authors of the report arrive at predetermined conclusions. Among the made-up citations were unique digital markers used by ChatGPT, called “oaicites.”

AI is “happy to make up citations,” said Steven Piantadosi, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of California at Berkeley. “The problem with current AI is that it’s not trustworthy. It’s just based on statistical associations and dependencies. It has no notion of ground truth.”

“We’ve seen this particular movie before, and it’s unfortunately much more common in scientific literature than people would like or than really it should be,” said Dr. Ivan Oransky, who teaches medical journalism at New York University and co-founded Retraction Watch, a site that tracks retracted scientific studies.

AI has caused similar problems in legal filings. In one case, former Trump fixer Michael Cohen used Google’s AI assistant to generate what he believed were real legal citations. His attorney then submitted them to a judge without verifying their accuracy.

From Ground News:

On Monday, OpenAI secured a $200 million contract from the Defense Department to create advanced AI prototypes aimed at addressing national security issues.

Depending on where you get your news, this could be seen as an exciting new government investment, or a potentially concerning use of AI technology.

With over 130 sources covering this story, Ground News exposes spin before you might mistake it for fact.

If you like The Preamble, you’ll love their app and website. It gathers the world’s perspective on the most polarizing issues and then breaks down each source’s bias and factuality. Their Blindspot Feed is proof that news isn’t just reported – narratives are crafted by partisan outlets we mistake as “unbiased.”

Ground News is nonpartisan and independently funded by readers like you.

Subscribe now for 40% off the same unlimited Vantage plan I use at ground.news/preamble.

The AI state

When AI works as it should, the results can be quite useful. Doctors now use AI to help diagnose diseases, for example. In one small study, ChatGPT was better than humans at diagnosing certain illnesses. AI can scan X-rays or MRIs and detect signs of cancer sometimes years before a human radiologist might be able to see it developing.

And from drug approvals to food safety, federal agencies are using AI in new and often beneficial ways.

The Food and Drug Administration said it plans to use AI to fast-track approvals for new drugs and medical devices, potentially cutting down processes that took a year or more to just a few weeks.

Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard said agencies are using private-sector AI tools to handle routine tasks like scanning documents, which frees up officers for more important work. She pointed to how AI helped accelerate the release of documents related to the Kennedy assassinations.

The State Department uses AI to help with office tasks like writing emails, translating documents, and summarizing articles. And the Patent and Trademark Office is using AI to sort and search patent applications more efficiently.

There’s no single watchdog tracking how the government uses AI — but there is one place the public can look. The Federal Agency Artificial Intelligence Use Case Inventory, created under the 2020 Executive Order on Promoting Trustworthy AI in the Federal Government, collects reports from the government on how it employs AI.

For 2024, the total number of federal government uses was more than 2,100. B Cavello, director of emerging technologies at Aspen Digital, told The Preamble that while the inventory doesn’t include all government uses of AI, “it does paint a pretty clear picture: AI use in the government is widespread and has been for several years.”

Who's watching the machines?

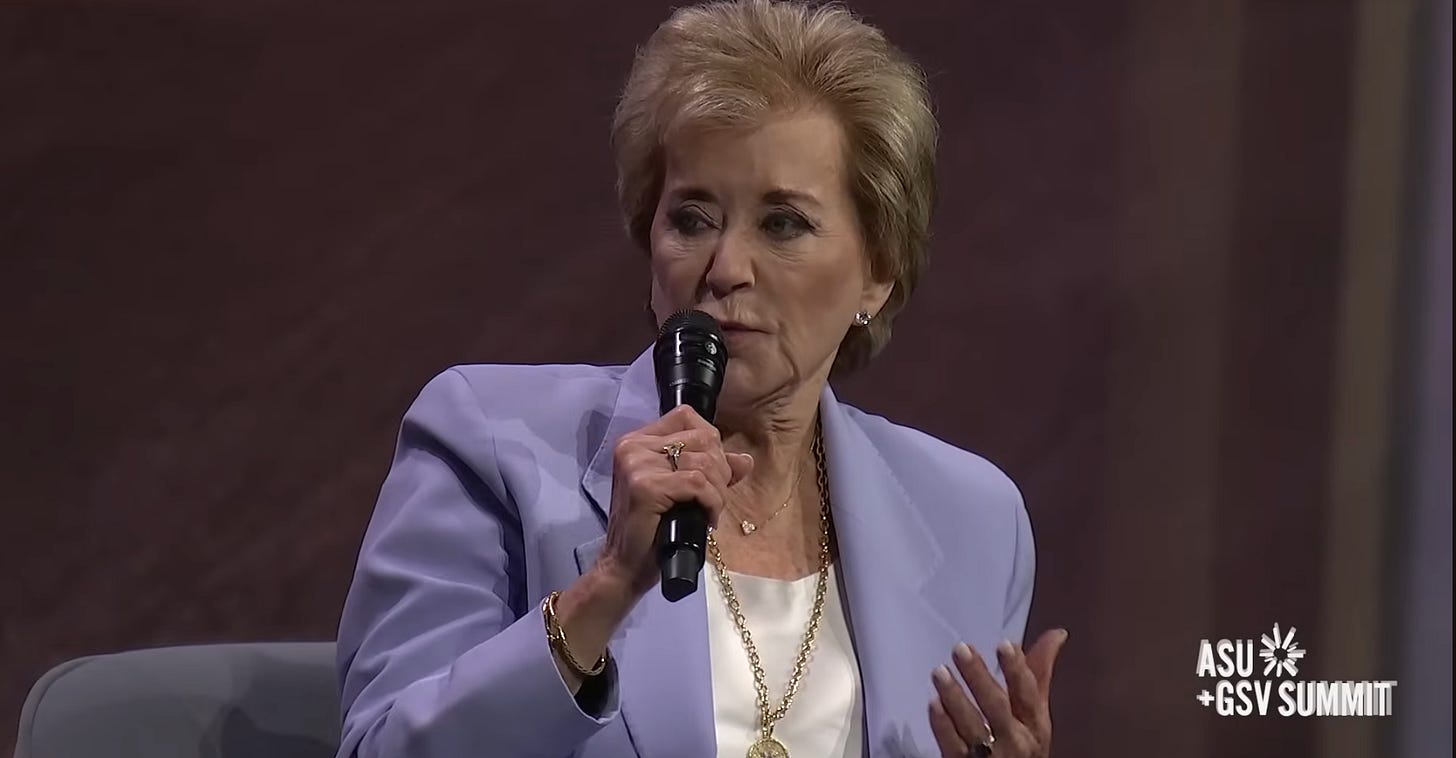

But not all public officials understand AI, even if they appear to speak confidently about it. Education Secretary Linda McMahon repeatedly referred to artificial intelligence as “A-1,” like the steak sauce, while speaking at an education summit: "A school system that's going to start making sure that first graders, or even pre-Ks, have A-1 teaching in every year, starting that far down in the grades — that's a wonderful thing!"

This isn’t just a failure of vocabulary. Ignorance about AI can become a public safety issue. If AI hallucinates and no one notices the mistake, it might insert a dangerous clause in a health care contract or misinterpret data in a security report. Or it might erroneously recommend canceling government contracts: DOGE used a hastily developed AI tool to identify cuts in the Department of Veteran Affairs, and it often hallucinated the size of federal contracts.

According to ProPublica, the AI DOGE was using said that some federal contracts were worth tens of millions, when in fact they were only worth tens of thousands. DOGE also used AI to help decide which federal employees to lay off as it slashed the government workforce by thousands.

“There isn’t really any one entity that is in charge of making sure” that government use of AI doesn’t cause harm, Cavello said. “While there are internal elements to the government like the inspectors general and Government Accountability Office, these organizations are not really equipped to oversee all of the many, many applications of AI in the government.” (President Trump has also fired at least 17 inspectors general.)

Maybe that’s why it’s still unclear who approved the final draft of the White House report with the fake citations — or whether anyone knew AI had been used in the first place. When asked whether AI had been used in the report, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt referred the question to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). HHS spokeswoman Emily Hilliard didn’t say where the fake citations came from, instead calling them “minor citation and formatting errors.”

AI is different from technologies that have come before it — not just in its potentially vast reach, but in the fact that even its creators cannot directly observe the enormously complex calculations it uses to generate information, and as a result do not fully understand how it works.

And it’s not always possible to undo the harm of a mistake. A flawed report can be retracted or revised — the White House issued an updated version of the children’s health report — but the damage to the report’s credibility and the public’s understanding cannot be fully repaired. If a bad AI recommendation permanently damages someone’s health or costs their life, nothing can be done. And if the government makes policy based on an AI report full of hallucinations, it could have an impact on millions of people.

The problems we’ve seen so far weren’t just small mistakes. They were warning signs. We trust AI more and more — but if we don’t know what it’s doing or who’s watching it, how can we trust it at all?

The short term thrill I had thinking that Andy Weir had written a new book that I somehow hadn’t heard about was absolutely crushed by the point of this article! 🤣

I knew a lot of this already because I’m so wary of AI and how it’s breaking down our brains. Students are using it to do assignments, homeschoolers are using it to lesson plan, workers are using it instead of their brains to read, etc etc. “But it saves time,” they all say. Bah! I feel like a grumpy old lady about it.

Not to mention the horrible environmental impact.

I hate that I can’t escape AI when I google something, too! Like, let me just use my brain to parse out what link I want, thank you.