A Muslim Socialist Just Beat a Cuomo.

But that's not even the real story.

Happy Independence Day! I’m sure your inbox will be filled with stories about the American Revolution and Frederick Douglass. Both worthwhile topics, to be sure. But today, we wanted to bring you something that will help you understand America more deeply. A story about how America is not one united front, but eleven rival cultures. When you’re done with this piece, American history will make so much more sense.

Wishing you every good thing this Independence Day, and always.

Sharon McMahon

Editor-in-Chief

Cameras flashed and cheers bounced off the walls as 33-year-old Zohran Mamdani took the stage in New York City. He looked around the large crowd in front of him, a smile broke across his face, and he declared, “We have won.”

Shouting to be heard over the noise of the room as it erupted in cheers, Mamdani continued. “Tonight, we made history,” he said. “In the words of Nelson Mandela, ‘It always seems impossible until it is done.’”

Eight months ago, when the state assemblyman from Queens launched his campaign to become mayor of the largest city in the United States, many thought it would be impossible for him to win the Democratic primary.

He was up against nearly a dozen other opponents, including the current comptroller, a former state assemblyman, a city council speaker, multiple state senators, and a hedge-fund executive. But Mamdani’s most formidable opponent was former New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, who was bankrolled by billionaires and a super PAC that raised $25 million. Cuomo had near-universal name recognition in the city, having led New York as governor for ten years. He racked up major endorsements from labor unions, despite his resignation in the wake of sexual harassment allegations and accusations that he lied to Congress during the pandemic about nursing-home deaths.

Polling just days before the election seemed to predict a Cuomo win. The New York Times, which said last year that it would no longer make endorsements in local elections, wrote an anti-endorsement urging voters not to choose Mamdani, because it considered his agenda unable to meet the city’s challenges.

But Mamdani said he was offering a different vision for New York, one in which the city’s 8.8 million residents “can do more than just struggle.” He proposed no-cost childcare, city-run grocery stores to control prices, and more hefty taxes on wealthy New Yorkers and big businesses. As a progressive Muslim candidate born in Uganda, Mamdani played the hand he was dealt and has now left many wondering: are candidates like him the future of the Democratic Party?

The answer is yes. But it’s also no. His win may seem like a long shot. But if you study American history, it’s not as surprising as you think. Our modern-day lens tends to magnify the united part of the country’s name and a shared American heritage.

But a deeper understanding of immigration and migration patterns reveals what lies beneath: 11 distinct, rival cultures that have developed and been maintained over the past several hundred years. These cultures are just as relevant politically today.

Mamdani’s primary win was possible, in part, because of New York’s position on the globe, an area that Colin Woodard — a bestselling historian and the director of the Nationhood Lab, a research institution — refers to as New Netherland.

The largest city in New Netherland was New Amsterdam, and the culture of New Amsterdam — later New York — was first formed by the Dutch who arrived at the advantageous trading port in 1624. At the time, the Netherlands of Europe were in their golden age, home to some of the world’s best universities and the cradle of modern banking practices. The Dutch founded the Dutch East India Company, the first large global corporation, which went on to have hundreds of ships, thousands of employees, and operations on multiple continents.

This culture — global, intellectual, capitalistic — welcomed people from many faith backgrounds, including Jews, Muslims, Christians, Quakers, and people from ethnicities that spanned from Moroccan to Spanish to Indian.

Unlike other colonies, like those of the New England Puritans, New Amsterdam was not trying to become a homogenous safe haven for one religion or to build a cohesive government structure. Like its Dutch founders, New Amsterdam was devoted to innovation, freedom of thought, and tolerance.

By way of example: In the 1650s, a group of Quakers tried to immigrate to New Amsterdam, and the governor attempted to limit how many could come, calling Quakerism a “new unheard of, abominable Heresy.” In response, the people of Flushing, a neighborhood in New Amsterdam, protested. They wrote that the law of the land extends love, peace, and liberty to all who come. Meanwhile, officials at the Dutch East India Company warned the governor not to “force people’s consciences,” but to “allow every one to have his own belief, as long as he behaves quietly and legally, gives no offense to his neighbors, and does not oppose the government.”

This is the cultural foundation of New York City. It’s embedded in the city’s DNA, passed down through its institutions, the families and businesses that put down roots, and the immigrants who flowed through the city’s harbor. That foundation has weathered storms, but it remains largely unshaken. The cultural region of New Netherland is still innovative, diverse, and trade-oriented, and it’s the culture that allowed a candidate like Zohran Mamdani to win.

Woodard explores these rival regional cultures in his book American Nations.

When the Puritans first disembarked on the shores of Massachusetts Bay, they set up their idea of a religious utopia among the forests of New England. They forbade anyone to enter their colony without first passing a test of religious conformity. Generally well educated and middle class, the pious Puritans established a government system that was meant to better the lives of all residents through public roads, schoolhouses, churches, and town greens. Families were given lots to live on. The Puritans believed government should be run by the community itself, without the interference of lords or kings. Each town within the culture of Yankeedom had its own elected officials. This was the cultural heritage of President John Adams.

Farther south was a completely different world. The settlers who landed in the swamps of Virginia were met with bugs and mud. But they had a plan: recreate the aristocratic society they had left behind in Europe. Founded mostly by the sons and grandsons of southern English gentry, the settlers of Tidewater created a culture with a focus on authority and tradition, landed estates, and enslaved servants to do the hard manual labor. This freed up the aristocrats to engage in headier pursuits. Men like Thomas Jefferson wanted to invent things, travel the globe, search for fossils, and begin universities.

And over the last two centuries, internal migration and immigration from other countries have, according to Woodard, further solidified the identities of the 11 rival cultures. At the founding, cultures like the Tidewater had very little tolerance for immigration at all, believing it to be a place for aristocrats and their offspring. Other cultures, including the Quaker-founded Midlands, believed in equality and acceptance for all. They welcomed immigrants with open arms.

Those ideals settled into the culture and impact many ideas of immigration today. About 36 million people immigrated to the United States between 1830 and 1924, and they did not spread out evenly, but instead settled in a few distinct locations, including New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago. Most of these immigrants were fleeing oppressive governments and cultures. They did not want to find themselves right back in a similar system upon arriving in America. So most immigrants avoided the Tidewater and Deep South, which had their own oppressive laws, including systems of enslavement and an ever more deeply entrenched social hierarchy that was difficult to pierce.

Internal migration was also self-sorting.

“People move because there are reasons to pull them to a place,” said Woodard. “They move because there are reasons to push them away from a place. And they tend to move to places where they already have existing connections, or where there is a fit in ethos between what they're coming from and what they're going to. Even if it's not a one-to-one match, it's never just a random movement of people. You don't just get on a boat, show up someplace, and then say, ‘Oh, okay, I'm gonna make a life here.’ Nobody does that.”

These 11 distinct cultures help us understand where a candidate like Mamdani could find success — and where it’s unlikely to happen. Take the Deep South: founded in 1670 by the settlers of another English colony, Barbados, an island in the southeastern Caribbean Sea. At the time, Barbados was the richest, oldest, and most densely populated colony in British America. As Woodard writes, Barbados made this wealth through a system of enslavement “whose brutality shocked contemporaries.” When the plantation owners there ran out of land on the island, they set their sights on the expanse of the American South.

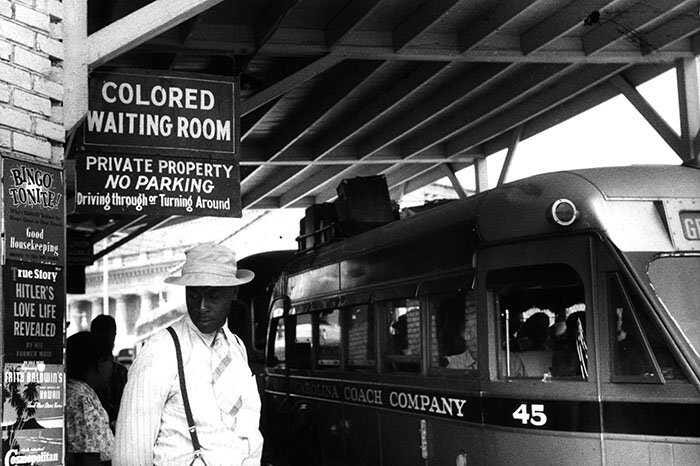

Once there, they imported shiploads of enslaved Africans and established a caste system, where one was born into a particular position in society and unable to leave it. Those from the dominant caste created laws to systematically oppress enslaved Africans. They outlawed relationships between Blacks and whites, decreed that anyone born to an enslaved person was also enslaved, and blocked Blacks from owning property. Meanwhile, Woodard writes, “like so many institutions in the Deep South, the caste system had convenient loopholes for the rich white men who created it.” This included having sexual relationships with Black women and girls — which was against the law — as long as the white man did it only for “fun.”

This caste system continued for centuries. After the Civil War, Black residents remained oppressed by Jim Crow laws that kept them away from schools, lunch counters, restrooms, and other public spaces used by white people. Poll taxes, property requirements, and literacy tests blocked Black citizens from voting, and racial terrorist groups like the KKK rained violence and death down on anyone who tried to create change.

Today, more than half of the Black population in the US lives in the South, and despite the legal end to enslavement and Jim Crow, they continue to hold less generational wealth than their white counterparts. As in New Netherland, the cultural heritage of the Deep South continues to impact voting patterns.

Because of the cultural remnants of the many-centuries-long caste system, a candidate like Mamdani might actually have a chance in some areas of the Deep South, according to Woodard. “You have a huge chunk of the population who obviously never supported this arrangement [the caste system], who [were] assigned to the subordinate caste [and were] against this the whole time.”

Southern Blacks, who may be less likely to support status quo, traditional candidates, might vote for a change agent like Mamdani. Programs that impact housing, education, and employment might be appealing to a culture that has historically been excluded from all three.

Meanwhile, candidate Mamdani would have little chance in Greater Appalachia, one of the last cultures to form during the colonial period. Settlers from northern Ireland, northern England, and the Scottish lowlands fled their war-torn countries and spread across Appalachia, which at the time was essentially lawless. As Woodard writes, they started “a civilization without a government.” They did not come to America to create a religious utopia or build estate homes; they came to escape oppressive governments.

That’s why these settlers focused on personal freedoms and independence from foreign rule. Wary of institutions, the population of Greater Appalachia remained as they began: rather lawless. They preferred vigilantism to the rule of law, and chose to rely, as Woodard says, “only on themselves and their extended families to defend home, hearth, and kin against intruders, be they foreign soldiers, Irish guerrilla fighters, or royal tax collectors.”

All this would make it a challenge for someone like Mamdani, who wants people to rely on government-funded programs, to be elected in the cultural region of Greater Appalachia today.

The seemingly intractable divisions in American politics are not new — they are readily apparent and have been present since the founding era. America is not one culture, but nearly a dozen rival regions. And as we ask whether the Mamdanis, Sanderses, Ocasio-Cortezes, or even the Cuomos represent the future of the Democratic Party, we might have to look just a little longer in the rearview mirror before what we see in the windshield begins to make sense.

You can find Colin Woodard’s book, American Nations, here. We donate all of our affiliate commissions to trusted nonprofit organizations, like World Central Kitchen, Undue Medical Debt, and Convoy of Hope.

This was fascinating and I finally was able to connect some thoughts that have been floating around my head for a while.

One thing though - does Mamdani want people to rely on government programs, or is he trying to create a culture where people know they can rely on government programs if they need them? One creates a new form of control, the other creates freedom by relieving stressors.

While interesting, there are many cracks (rips?) in this fabric of America. I live in Texas, which is a part of the “Greater Appalachia” according to Woodard. Over the last decade I have seen a few things that make me think this is more of a rear view mirror than windshield idea. I have seen a city and community that looks more like New York than Texas. We just elected a Muslim mayor (our city keeps mayoral races non partisan.) We successfully defeated Mom’s for Liberty school board candidates. We fly our Pride flags, Palestine flags, and support our local city library. Our school district sends home important papers in multiple languages, and our neighbors run a refugee outreach center. I’ve also seen Republicans in Texas do whatever they can to change the rules to win and maintain power, all while campaigning to fix problems that they’ve created. I’ve seen billionaires buy our governor and help primary opponents to get his school voucher bill passed, that was a majority of Texans did not approve of. Tarrant county is currently going through redistricting/gerrymandering issues, and Trump himself called on our governor to redraw (aka gerrymander) the Dallas area district so Rep Jasmine Crockett cannot win. Our voter ID laws contribute to some of the worst voter suppression. The Republican’s behavior can be explained by this cultural view of America’s past, but America’s present and future is breaking through, and seeing a candidate like Mamdani succeed (even so far away in New York) is going to appeal to many of us who are more than willing to rip this old fabric to shreds.