A League of Their Own — Again

The forgotten history of women’s professional baseball — and the women bringing the league back.

Sophie Kurys dug her cleats into the sand and sidled a few inches away from first base. Energy buzzed through the stadium. Game six of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) playoffs had already burned through 13 innings, but neither the Rockford Peaches nor the Racine Belles had any runs on the board.

The Belles were up three games to the Peaches’ two in the seven game series. But the Peaches’ two pitchers had proven to be a dominating force on the field during this match, and the Belles had not made it on base until the extra innings.

Kurys had a plan. With over 200 stolen bases under her belt, she’d already set the league record that season. As Peaches’ pitcher Millie Deegan began to move her arm, Kurys burst into motion. She sprinted towards second and slid headfirst across the base as the batter struck out. She stood up, brushed the dirt from her canary yellow skirt, and straightened her hat. Then she began to eye third.

Belles player Betty Trezza was next up to bat. When Deegan began to wind up, Kurys took off again.

She heard a crack and turned her head to see that Trezza had hit the ball to right field. As Kurys reached third base, her manager screamed, “Go! Go!”

So Kurys kept running. Seconds later, she slid into home plate.

“SAFE!” shouted the umpire. The 14th grueling inning had finally ended with a single run. The Belles were the 1946 champions.

The crowd of over 5,600 people erupted into cheers as the Belles rushed out of the dugout and onto the field. Fans soon followed, and Kurys was lifted into the air.

Kurys wasn’t the only one setting AAGPBL records in 1946. Started years before as a way to boost morale and keep baseball alive while men were at war, the league had drawn hundreds of thousands of viewers that season — the attendance at Belles games alone could be anywhere from 2,000 to 4,000 — and had become a family attraction. An excerpt from the 1947 yearbook of the Fort Wayne Daisies said the league was “the most successful sports venture to attract the general interest in many years.” By 1948, the games were drawing nearly 1 million fans per season.

But despite this success, the AAGPBL was shut down less than ten years later. And for 70 years since, women ballplayers have found themselves shut out of the sport and struggled to make space for themselves even on the sidelines.

All that is about to change, when women baseball players finally get a new league of their own.

Swing, batter batter, swing

Baseball became hugely popular in America in the 1920s and 1930s thanks to players like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. The game captivated wide audiences, and the increasing interest led to the construction of the original Yankee Stadium in New York in 1923 and the expansion of Boston’s Fenway Park and Chicago’s Wrigley Field in the 1930s.

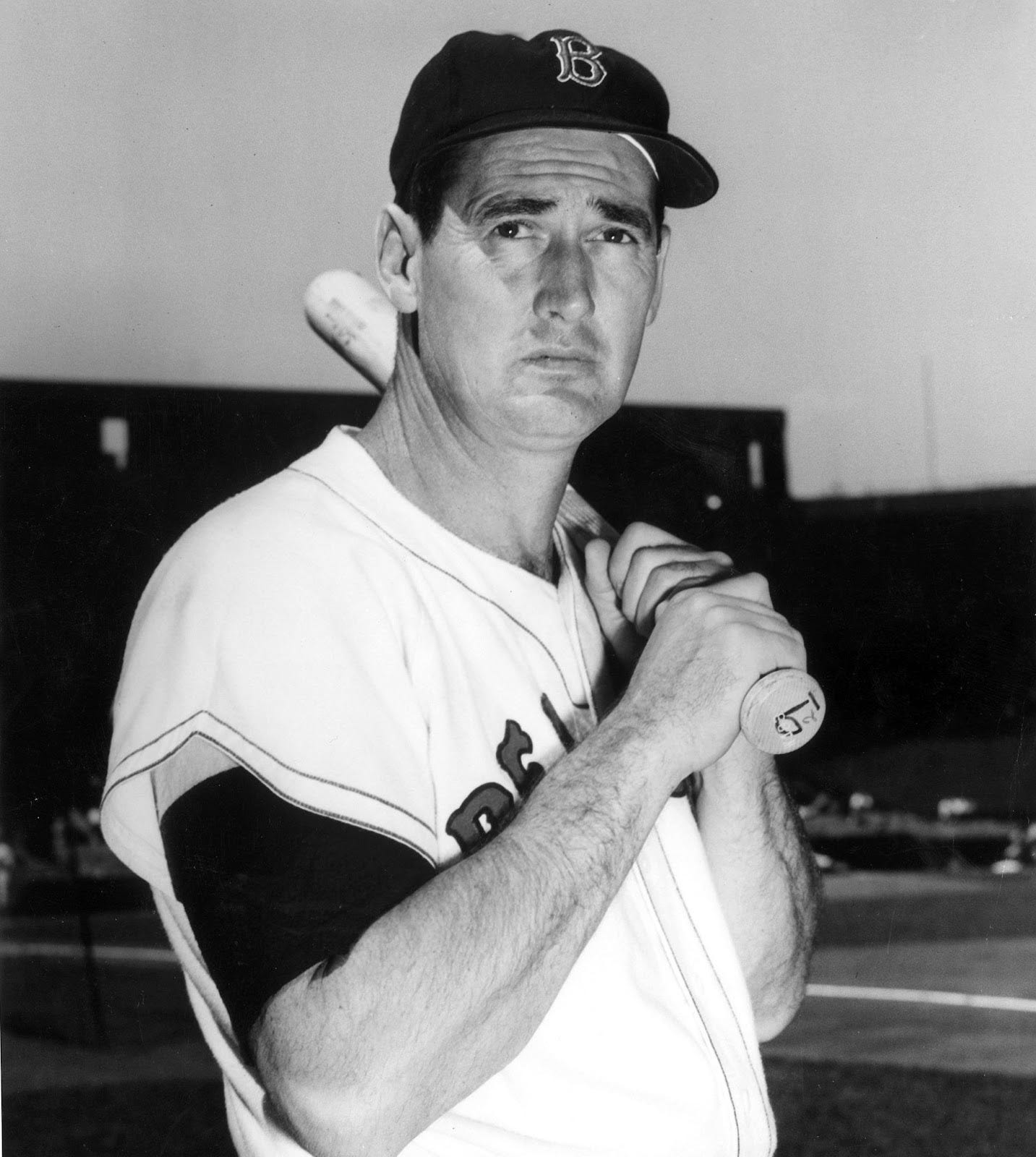

But construction stopped when America entered World War II and young men 18 and over joined or were drafted into the armed forces in droves. Over 90% of active players went on to serve in the military, including Ted Williams, one of baseball’s most famous legends (he returned to baseball when the war ended). Due to a lack of men, many minor league baseball teams disbanded, and owners of major league baseball fields and teams grew concerned about what would happen to the game.

So Philip Wrigley, the gum magnate who owned the Chicago Cubs, suggested putting women on the field.

Out of that idea, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, or the All-American League, as it came to be known, was born in 1943. At first, the rules differed from men’s baseball in a couple of ways. The women would use regulation baseball bats and cleats, but they would play with softballs instead of smaller baseballs, and the diamonds would be smaller. The teams tried to get notable male athletes as their managers, thinking that would boost interest in the league.

But they still needed players. A team of former male athletes started crisscrossing the US and Canada to scout softball games. They set up tryouts in dozens of major cities. Hundreds of women showed up, and 75 were invited to the final tryouts in Chicago. There, league officials scrutinized the players as they ran drills throwing, catching, running, sliding, and hitting. They were also judged on femininity, a high priority for the league because it was convinced fans expected traditionally feminine women.

In short: they wanted the athletes to look like ladies and play like men.

The 75 women were so excited about the prospect of playing ball that some tried not to answer their hotel phone the night of the last tryout, fearing they would be told to pack up and head home. Fifteen of them did get that call, but 60 were chosen and separated into four teams.

Making the league was life-changing for many of them, some as young as 15. The contracts ranged in pay from $45 to $85 a week, depending on skill, experience, and age, and the girls were sent to live in private homes in the league cities. They would stay in hotels on the road.

“I was only 16, and I’d never been more than one hundred miles from home, and I’d never ordered or eaten a meal out,” Audrey Haine told Jim Sargent, who published the book We Were the All-American Girls: Interviews with Players of the AAGPBL.

With the teams assembled and the games scheduled, it was time to see whether people would come see women play ball. One of the biggest marketing tools was the women themselves: They had to follow strict rules of conduct and appearance. This meant lipstick and rouge while on the field, and no drinking or smoking in public while off the field. Hair had to hit below the collar, and their uniform included satin skirts.

“ALWAYS appear in feminine attire when not actively engaged in practice or playing ball,” one rule said. Another: “All social engagements must be approved by chaperone. Legitimate requests for dates can be allowed by chaperones.” After playing games all day, the women were required to attend charm school at night.

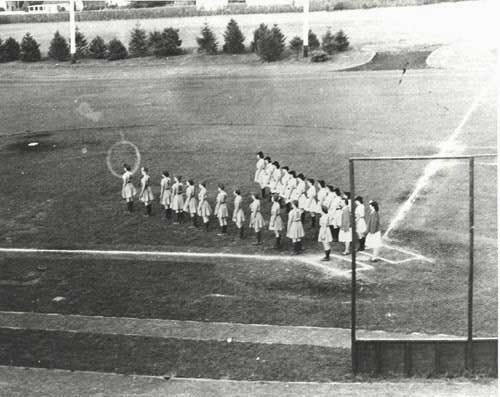

They stuck to a grueling schedule, getting up at dawn every day and playing in 90 to 110 games per season. At the start of each game, the two opposing teams would form a “V for Victory” from home plate down the first and third baselines. “The Star-Spangled Banner” would echo through the stadium before the first pitch.

The crowds loved it. And very quickly it became clear that the women were just as talented as the men. So talented, in fact, that the league soon switched to using baseballs instead of softballs and increased the size of the baseball diamond.

Dottie Kamenshek’s career shows the level of skill these players had. During her ten years with the Rockford Peaches, she struck out only 81 times in 3,736 at-bats. Sports Illustrated named her one of the top 100 female athletes of the century in 1999, and she was so good that a minor league men’s team offered to buy her contract in 1947 (she declined, thinking it was a publicity stunt and that they wouldn’t actually let her play). During the 1946 season alone, she stole 109 bases. Because of the skirts, this was a painful activity, and many women developed a “strawberry” on their upper thigh. “We got used to it,” Kamenshek said. “In the spring, we’re always hoping we’d develop calluses.”

Or consider Helen Callaghan. Known as the “feminine Ted Williams” and “a little bundle of dynamite,” Helen played five seasons and won a battling title, stole more than 100 bases twice, and was one of the most competitive ballplayers the game has seen. She described her time in the league this way: “Fun times, but we played tough, even when we were hurt. After a doubleheader, we’d shower, get dressed, travel all night on the bus, get to our hotel at 8 or 9 in the morning, shower, play two games of baseball in 110 degrees of heat, then do it all over again the next day.”

Helen’s son Casey Candaele also went on to play in the major leagues. When asked whether he got his athletic ability from his mom, Casey said no, it was from his dad, because “if I got it from my mom, I’d be in the Hall of Fame.”

Kamenshek and Callaghan were some of the inspirations behind the movie A League of Their Own, which was based on the AAGPBL. Kamenshek is the reason Geena Davis’s character is named Dottie.

Over 600 women played professional ball in the league. For the athletes involved, baseball provided opportunities rarely available to women during that era. Their salaries were higher than those typically available to people of a working class background, and players were able to afford higher education after they left the league. After their playing years, 35% of the AAGPBL players earned a college degree (at the time, only 8.2% of women were getting college degrees), and 14% went on to receive a master’s degree. The league also helped instill a sense of empowerment and personal autonomy on and off the field, and the players became an inspiration for other women around the nation.

But by 1954, interest in the league had waned. Traditional marriage and home life increased in popularity in the 1950s, and the image of what a woman should be changed. Television broadcasting became more popular, increasing competition for people’s attention, and advancements in travel and leisure opportunities pulled people away from baseball stadiums.

But the league stayed in the back of the players’ minds. “Sports can help girls in many ways, and I became an advocate for girls in sports by the end of the 1940s,” says Mary Pratt, who played for the Rockford Peaches and the Kenosha Comets, in We Were the All-American Girls. “The difference between girls playing sports today and those who played in the All-American League is that we had to dress, act, and look like ladies in addition to playing ball well. I believe our league elevated the level of competition in sports.”

A resurgence 70 years later

Ever since the All-American League players hung up their mitts, there have been occasional attempts to start another women’s baseball league, or just to create more opportunities for women in baseball in general. There is no formal high school or college baseball program for women as there is in soccer and basketball. The Women’s National Team was founded in 2004 and competes in international tournaments like the Baseball World Cup. Softball remains an option, but it is a different sport (because of not just the larger balls and smaller fields but also the different pitching technique — softball is underhand while baseball is overhand).

Behind a lot of the effort for more women in baseball is Justine Siegal, who was told at 16 by a coach that she was wasting her time pursuing a career like his. “He just laughed at me and said, ‘No man will ever listen to a woman on a baseball field,’” she said. “I started thinking, ‘Who’s he to decide what I’m going to do?’ So I went on this big pursuit.”

In 2003, she founded the Sparks, an all-girls baseball team that played against boys, and six years later she proved her old coach wrong when she was hired as a guest coach for the Oakland A’s instructional league, a post-season development program. In that role, she helped pave the way for MLB to hit an all-time high of 43 women coaches in 2023.

Along the way, Siegal started Baseball For All, a national nonprofit that teaches girls to play and coach. It is now the largest girls’ baseball organization in the US.

But she wasn’t done. This year, hundreds of women tried out for Siegal’s newest venture: the Women’s Professional Baseball League (WPBL), co-founded with Keith Stein, CEO of the Toronto Maple Leafs.

“The Women’s Pro Baseball League is here for all the girls and women who dream of a place to showcase their talents and play the game they love,” said Siegal. “We have been waiting over 70 years for a professional baseball league we can call our own. Our time is now.”

The league is set to kick off next May, starting with four teams (in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston, chosen because of their market size and fan presence and because they are “storied sports cities,” as Siegal put it). It hopes to have a regular season schedule of about 40 games per team, then playoffs. Each team will be made up of 15 players, and the games will all be played at two or three neutral sites, which are still being determined. Salaries will be comparable to those in minor league men’s baseball.

The All-American League is not far from Siegal’s mind. AAGPBL pitcher Maybelle Blair, who turned 98 in January, is an honorary chair of the WPBL’s advisory board. Siegal said there is an “obligation” to make former AAGPBL players “proud of this league.” As interest in women’s sports increases and other major leagues expand to include women’s teams — including a new Women’s National Basketball Association team planned for Philadelphia in 2030 and teams in Boston, Atlanta, and Denver being added to the National Women’s Soccer League in the coming years — the time seems right for WPBL to jump into the fray.

Blair, along with AAGPBL player Jeneane Lesko, attended the WPBL tryouts this fall. “It’s actually one of the best times of my life,” Blair said. “It reminds me of when I was playing ball and had the opportunity… I’m reliving my life again through these girls. I think every girl should have an opportunity to play the sport that they love.”

She continued, “I never [in my whole] life ever figured that we would have another ‘league of their own.’ And here it is: my dream… We’re going to make this thing and go and show that women can play baseball.”

Great story! Very inspiring.