$15 Million of Your Tax Money is Going to This Dictator

Plus: Only 11% of spots left. Here's why that matters.

Want more than just hot takes and headlines? Governerds Insider is almost full—89% of spots are already claimed. This is where smart, curious people come together to read bold books, meet unforgettable authors, learn with workshops and deep dives, and have the kind of conversations that actually matter. It’s not just a book club—it’s your place to think deeper, laugh harder, and feel more hopeful in a chaotic world.

If you’ve been waiting for a sign, this is it. Click here if you’re curious!

Now for today’s feature:

The story of Kilmar Abrego García — a Salvadoran man wrongfully deported from Maryland to El Salvador— pulls back the curtain on a growing alliance between President Donald Trump and President Nayib Bukele, El Salvador’s self-anointed “world’s coolest dictator.”

But this isn’t just a Trump bromance with a charismatic strongman. It represents a concerning shift in the approach to governance and criminal justice, one where human rights, due process, and even national borders become negotiable for the right price. And the implications stretch far beyond immigration policy.

Trump’s Backdoor Deportation Strategy

Last month, the Trump administration decided that instead of deporting hundreds of detained Venezuelan migrants to their home country, it would ship them off to El Salvador—1,600 miles from Venezuela.

President Trump's choice of El Salvador as a deportation destination stems from his campaign promise to implement mass removals of undocumented immigrants. Frustrated by legal barriers to traditional deportation, his administration dusted off the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 — a wartime relic rarely used in modern times — to fast-track deportations without legal hearings. During World War II, the Alien Enemies Act was used to detain Japanese and Japanese Americans living in America without evidence of actions threatening US national security.

Today’s targets are alleged members of Tren de Aragua, a violent Venezuelan prison gang that has spread to several Latin American countries and expanded its reach into the United States. The gang's activities in America reportedly include a series of robberies, and members have been implicated in serious violent crimes, including the shooting of two New York police officers and the murder of a former Venezuelan police officer in Florida.

Law enforcement has arrested suspected gang members across multiple states, including Pennsylvania, Florida, New York, Texas, and California. The Biden administration designated Tren de Aragua as a transnational criminal organization in 2023, and one of President Trump’s first acts in office was to designate the gang as a foreign terrorist organization.

The group’s actual U.S. footprint is small—estimated at around 600 members among 770,000 Venezuelan immigrants—but the political utility of stoking fear is enormous. Critics say many deportees are identified by questionable indicators like rose tattoos or clock imagery, symbols common far beyond gang circles. In other words, if you’re Venezuelan and inked, you’re suspect.

Bukele’s brutal theater

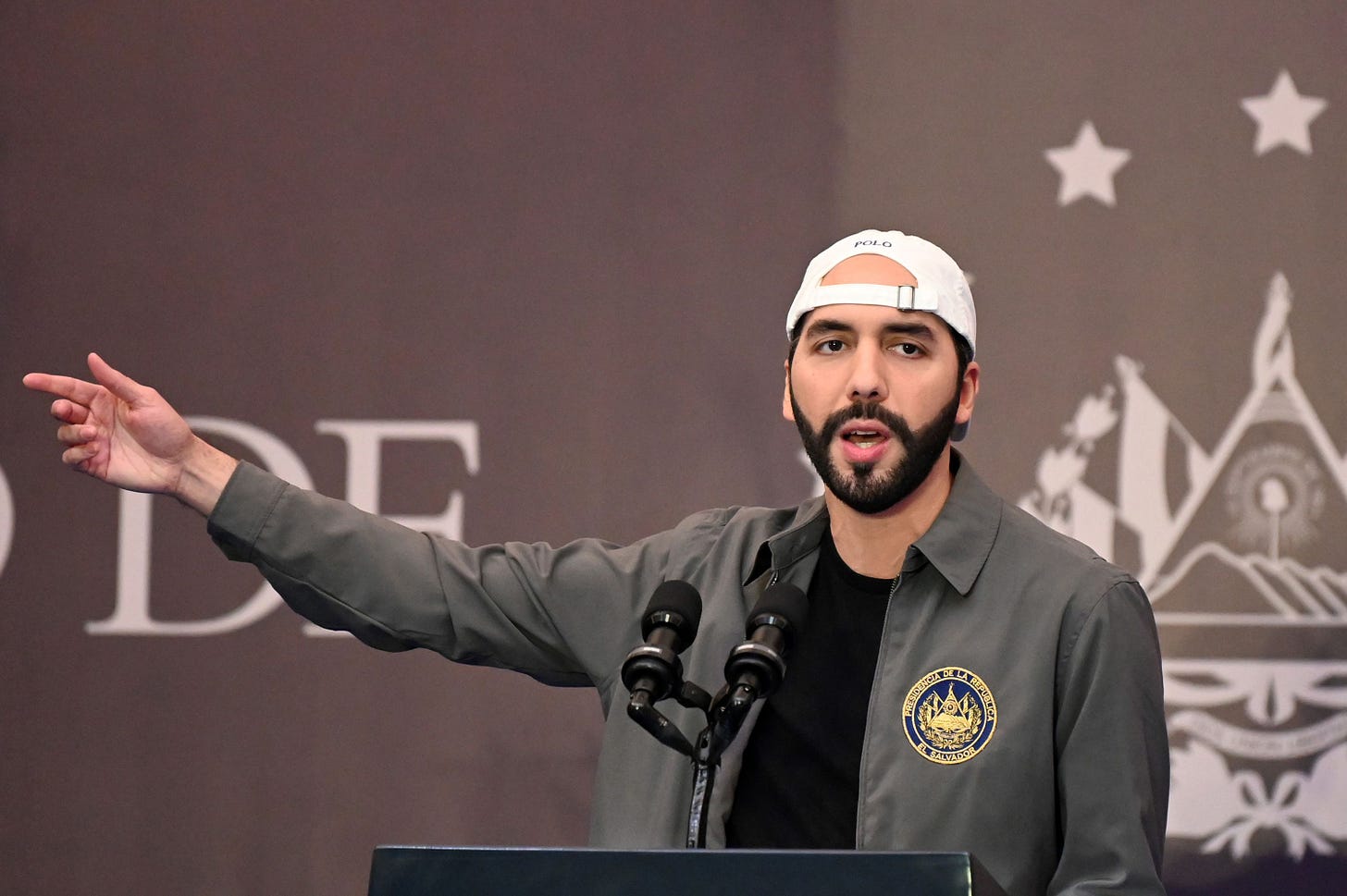

Bukele, a former advertising executive who came to power in 2018, presents himself as a modern, tech-savvy outsider breaking from El Salvador's traditional political establishment. He made El Salvador the first country to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender, and presents himself as a "philosopher king" rather than a traditional politician. Bukele maintains an active social media presence, becoming one of the most-followed world leaders on TikTok, and cultivates a youthful image—often appearing in jeans, leather jackets, and backward baseball caps rather than traditional suits.

Bukele's popularity stems primarily from his dramatic reduction of El Salvador’s gang violence, building a brand on iron-fisted anti-gang crackdowns that have slashed El Salvador’s once-staggering murder rate. For ordinary Salvadorans who lived in terror of MS-13 and Barrio 18 gangs for decades, this transformation is palpable in daily life— they can now move freely in former gang territories, go out at night, and use public spaces without fear. As one taxi driver told Time, "Anyone who did not live through the terror of life under the gangs will never understand how much things have changed."

But Bukele shredded civil liberties in the process. After a deadly weekend of gang violence in March 2022, Bukele declared a “state of exception,” which is meant to last only 60 days. But instead of its limited use, Bukele has renewed this state of exception three dozen times now. The emergency decree suspends basic rights, allowing police to arrest anyone suspected of gang ties—no warrant, no lawyer, no explanation.

As a result, El Salvador now holds the world’s highest incarceration rate. Roughly 2% of its population is behind bars. Over 70,000 people have been imprisoned since Bukele declared this state of exception, many with no connection to gangs at all. Bukele chalks up the wrongful incarcerations to “collateral damage” or the “margin of error.”

At the center of this system is CECOT—the Terrorism Confinement Center. Built in 2023, the 40,000-capacity mega-prison is a concrete dystopia where prisoners are stripped, shaved, crammed into 80-person cells with no beds, no rehab programs, no daylight, and no contact with the outside world. Bukele boasts: “They don’t see the light of the sun ever.”

Human rights groups say hundreds have died in custody—beaten, tortured, or denied medical care. But none of that has dented Bukele’s sky-high approval ratings: His Nueva Ideas party controls 54 of the country's 60 congressional seats. And the latest CID-Gallup poll published last fall found 91 percent of respondents approved of his presidency and his methods in curbing gang violence. In fact, leaders in Colombia and Honduras have promised to emulate his crackdown.

The Trump-Bukele deal

Bukele first met Trump during his first term and has cultivated ties with American conservatives ever since. He's given interviews to Tucker Carlson, spoken at CPAC and the Heritage Foundation, and hosted Florida Representative Matt Gaetz at his lakeside retreat.

Their formal deportation partnership began taking shape this past February when Secretary of State Marco Rubio visited El Salvador and announced Bukele's offer to house "dangerous American criminals."

For Trump, it’s a win-win. Bukele has offered the United States, in his words "the opportunity to outsource part of its prison system…for a fee.” The news that the U.S. is sending undocumented migrants to the country’s notoriously harsh prison system has created a powerful deterrent for those considering crossing the border illegally.

While visiting El Salvador, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem posed for a selfie and took a video at CECOT surrounded by rows of bare-chested tattooed inmates standing inside their crammed cell with a tough-talking message: “If you come to our country illegally, this one of the consequences you can face.”

Bukele’s media team also churns out glossy, stylized footage of shackled men stumbling off military transport planes, heads bowed, lined up like dominoes for public shaming as guards shave their heads. Trump praised these theatrical displays of punishment during Bukele's White House visit as exactly what "people want to see."

Kilmar Abrego García illustrates the human cost of the Trump-Bukele partnership. Deported on suspicion of MS-13 affiliation — claims his lawyers vigorously deny — he was shipped to El Salvador in what the Justice Department later admitted was an “administrative error.” When U.S. courts ordered his return, both governments shrugged. Even after the Supreme Court told the administration to “facilitate” Abrego García’s return, Bukele scoffed: “How can I smuggle a terrorist into the United States?”

It’s a legal catch-22: The U.S. says it can’t bring him back. El Salvador says it won’t. The courts say it must happen. And no one moves. This isn’t system failure. It’s the system working exactly as designed—to terrify, to confuse, to abandon the rule of law in favor of performance.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration is sweetening the deal. According to Maryland Senator Chris Van Hollen, who met with Abrego García in El Salvador, the White House pledged $15 million to detain deportees—including Abrego García—in Salvadoran facilities.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio has publicly praised this arrangement, calling it a way to hold migrants in "very good jails at a fair price that will also save our taxpayer dollars".

And it doesn’t end there. Trump has jumped at Bukele’s idea to detain American criminals— including U.S. citizens and legal residents — for a fee, saying he’d accept “in a heartbeat” if it’s legally possible. At the White House, he was overheard telling Bukele: “The homegrowns are next. You got to build about five more places.”

Legal black holes

Legal scholars are understandably alarmed. Sending US citizens to a foreign prison system without due process would almost certainly violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Bukele’s model allows the Trump administration to bypass institutions, deliver results, and create legal knots that are difficult to untangle.The Trump-Bukele alliance offers a chilling glimpse into how authoritarianism travels—not just through ideology, but through contracts, propaganda, and shared impunity. One country exports prisoners. The other exports the playbook.

Here’s the link to Governerds Insider one more time — seats are already very limited!

This is Elise's most hard-hitting article yet, and I appreciate that: no mincing words! But I'm so so so angry that this is happening.

I know I'll likely be disappointed, but I want to go back to all those Trump voters Sharon surveyed last month and ask if they still support him. But I fear that the sunk cost and propaganda is too powerful. Meanwhile, other than a few gems like Van Hollen, our electeds only care about lining their own pockets (see yesterday's article on insider trading).

We can't wait for them: WE save us, together. Keep attending the Hands Off and Tesla Takedown protests. Care for your neighbors. Keep calling your reps. We can do this.

When I walked out of the theater earlier this year after watching "I'm Still Here," I was reflecting with my friends how the film reframed my understanding of modern authoritarianism. The Brazil depicted wasn't a constant display of military parades, but rather a society where repression operated behind a carefully maintained façade of normalcy. Families still enjoyed ice cream outings and beach parties while their neighbors quietly disappeared. The genius of this system wasn't that it eliminated freedom entirely, but that it made the sacrifice of others' freedom feel distant and abstract to those not directly affected.

What's particularly alarming about the Trump-Bukele partnership is how it normalizes extrajudicial punishment through economic incentives, creating a template for authoritarianism that feels distinctly American. By outsourcing incarceration to another country, the administration creates a jurisdictional limbo where legal protections become irrelevant, reminiscent of earlier experiments with Guantanamo Bay. The $15 million payment transforms human rights abuses into simple business transactions, while the theatrical public humiliation of detainees serves as powerful propaganda. Most concerning is how easily Americans might accept this arrangement – not because they embrace authoritarianism outright, but because it comes wrapped in familiar packaging: pragmatism, efficiency, and the promise of safety (a safety that seems threatened even despite the low numbers in the statistics provided by Elise).

El Salvador's citizens praise Bukele for allowing them to finally enjoy concerts and public spaces without gang violence, but this newfound "freedom" masks the wholesale abandonment of due process for everyone, not just the tens of thousands behind bars. Let’s not dismiss the horrible situation that pre-Bukele Salvadorans were faced with. It’s not like being afraid of stepping outside your front door is an example of freedom. But the popular solutions they received to solve the problem are ultimately just sweeping the issue under the rug in an unsustainable way.

Authoritarianism has already arrived in America, via outsourcing – it didn’t arrive with tanks in the streets or dramatic martial law declarations. Instead, it came draped in the American flag, to be celebrated at football games, to be justified from pulpits, and to be validated by academic institutions that have been extorted into compliance. The Venezuela-to-El Salvador deportation scheme offers a perfect case study: it bypasses legal hurdles, creates jurisdictional black holes beyond constitutional reach, and packages human rights abuses as pragmatic solutions to complex (exaggerated) problems. These gangs do exist and are dangerous, but I would have hoped that I wouldn’t be asked to suspend my essential legal rights for fear of something that isn’t likely to affect almost anyone’s ability to live their life.

Today it's Venezuelan gang suspects identified by questionable criteria like tattoos; tomorrow it could be domestic protesters or political opponents, or suspects based on who they follow on Substack, all processed through systems designed to operate beyond the reach of constitutional protections or public scrutiny.

What makes this approach so insidious is its plausible deniability. Citizens can still enjoy their daily lives and maintain the comforting fiction that they live in a free society, even as the foundations of that freedom are systematically dismantled for those deemed problematic. The Trump-Bukele model doesn't require widespread repression – just targeted action against marginalized groups that the majority can be convinced to fear or ignore, all while the machinery of entertainment and consumption continues uninterrupted. This is authoritarianism custom-built for American sensibilities: outsourced, profitable, entertaining, and wrapped in the language of practical problem-solving rather than ideological revolution.