“Whoever claims to be in the light but hates a brother or sister is still in the darkness.”

—Jesus, 1 John 2:9

“We have abundant reason to rejoice that in this Land the light of truth and reason has triumphed over the power of bigotry and superstition, and that every person here may worship God according to the dictates of his own heart. In this enlightened Age and in this Land of equal liberty it is our boast that a man’s religious tenets will not forfeit the protection of the Laws, nor deprive him of the right of attaining and holding the highest Offices that are known in the United States.”

—George Washington, who owned people

I’d like to begin and end these comments on Christian prejudice by telling you a bit about my paternal grandfather.

My grandfather was named Leonard, and sometimes went by Lenny. He was a real old-school Brooklyn guy, with an accent you hear nowadays only in old movies. He said things like “cock-a-roach,” and pronounced Broadway “Broad-WAY.” He was a house painter who had painted the homes of both Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Bob Keeshan (a.k.a. Captain Kangaroo). This impressed me deeply as a child, and honestly it still does.

Later, as my grandmother’s health declined, my grandparents moved out near us on Long Island and became a regular part of our lives. Leonard was kind and warm, and he dutifully cared for my grandmother through several brutal years of declining health.

He was also a rather prejudiced working-class white guy from Brooklyn, and bigoted against many, many types of people. It was from him that I first learned:

“Da Blacks cause all da crime.”

“Da Jews killed Jesus Christ.”

“Da Pawta Rickens take all da jobs.”

My mother, who loved and cared for her father-in-law, would politely refer to him as “Archie Bunker” when he wasn’t around.

He was also a devout Catholic who never missed Mass. But even at church, my grandpa found ways to discriminate. He would receive Communion wafers only from an actual priest, and staunchly refused to take bread and wine from any plainclothes Eucharistic ministers — including my dad. If we were in line for Communion and Grandpa could see a civilian, not a priest, dispensing the host to his line, he’d abruptly switch lines to make sure he received from the real deal. “I only take da Holy Eucharist from a Cat-lick priest,” he’d tell me.

I swear, in my memory he called it “the Holy Uterus,” but I’m sure that’s not the case.

My mother would later share stories of harrowing arguments my dad had with his own father over dinner, shouting fights about civil rights, Nixon, and the Vietnam War. But for years, I was too young to know I had a prejudiced grandpa; he was always very loving and kind, even if he constantly smoked in the house.

Before I had the vocabulary to put such confusion into words, I’d notice how tense Mom and Dad got every time Emmanuel Lewis would pop up on TV in a Burger King commercial and Grandpa would call him “Da little colored kid.” And that was one of the more benign comments.

Many of us have had family like this; many of us have loved family like this; and many of us have struggled with the impression that prejudice and Christianity seem to be a package deal.

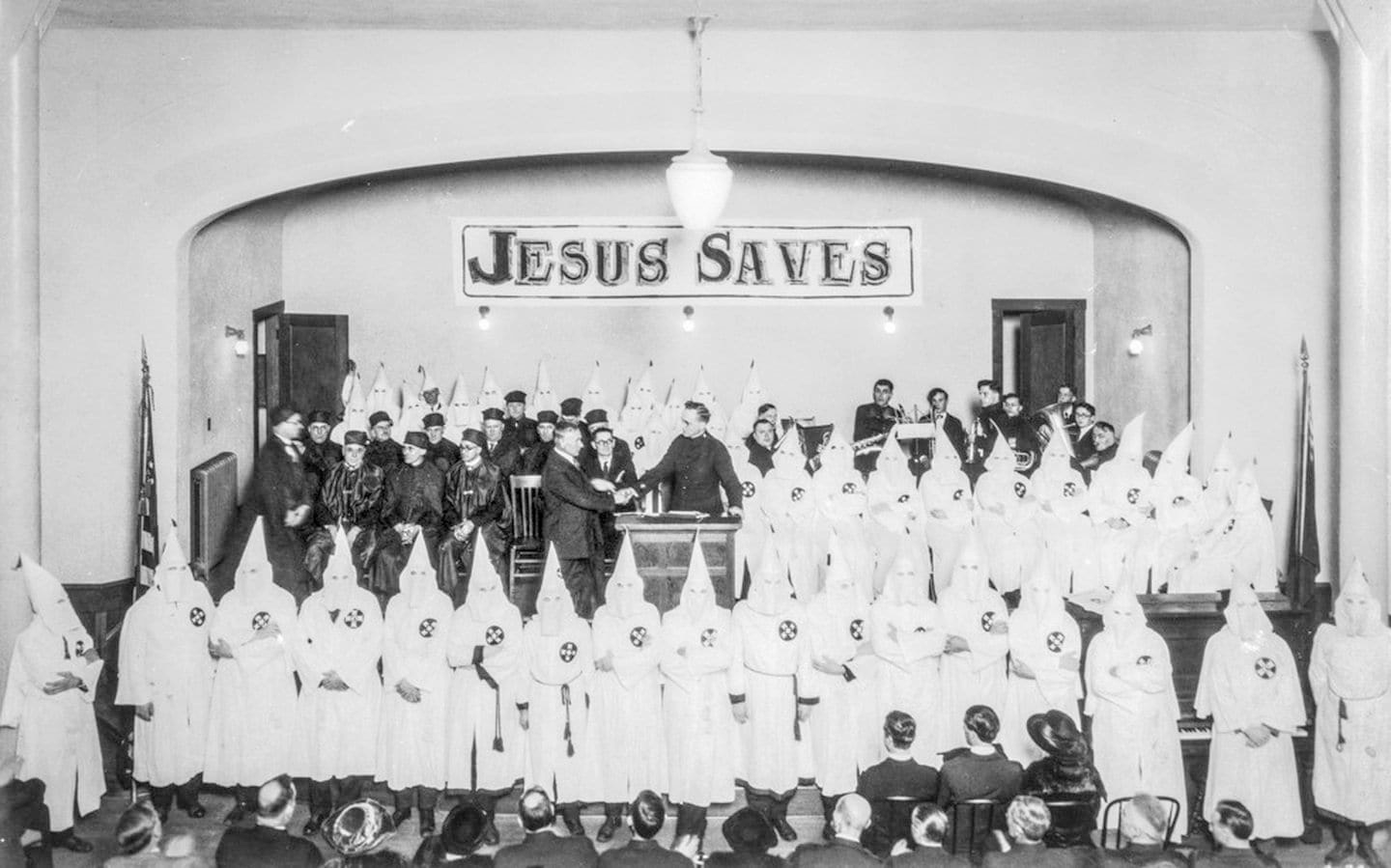

Modern white supremacy exists on a broad, and expanding, spectrum. From the KKK, neo-Nazis, and armed militias to bloviating public intellectuals lending credibility to white replacement theory, from dog-whistle politicians and media to smiling church folk who oppose every racial justice movement, generations of white Christians have resisted any changes to a racially exclusive status quo.

Some of the most heinous acts of white supremacist violence have been carried out by individuals or groups who claimed to serve Christian values, from the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing of 1963 to the Charleston church massacre of 2015 and the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville.

But white supremacy is a system that can’t be reduced merely to its most violent expressions. Supremacists don’t all necessarily hate anyone; it’s often easier to just stay pleasantly indifferent to racial injustices and talk vaguely about “traditional demographics” and “heritage.”

But all forms of white supremacy — belief in the superiority of white people over others — stand in direct contradiction to the life and teachings of Jesus, who consistently commanded love for all people, especially the persecuted or marginalized. Jesus was about humbling oneself, not exalting one’s own group. White supremacy divides humanity into superior and inferior groups, giving a pasty middle finger to Jesus’s message of radical unity.

Christian theology teaches that every person is made in the imago Dei — the image of God (Genesis 1:27). White supremacy rejects this by implying that some humans look more like that image than others.

In Luke 4:24–27, Jesus enraged his own townspeople by reminding them that God could bless despised outsiders like Phoenicians and Syrians while Israelites suffered. He totally lost the crowd by dismantling the kind of exclusion that supremacist ideology requires.

When white supremacists chant “You will not replace us” or desperately claim that they must protect “white heritage” through cultural domination, they’re aligning themselves with the rich fool who hoards treasures on earth (Luke 12:13–21), not with Jesus.

And don’t tell your racist cousin, but placing racial preference above Jesus’s commandments to love technically counts as idolatry. Jesus said that God’s kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36) and our earthly divisions should not dictate spiritual truths.

No one can serve both Christ and white supremacy. It’s not merely un-Christian; it is anti-Christian.

Slavery, with Ham

America is the only nation on earth where Christianity has been historically entwined with white supremacy from the beginning. Slavery, and the succeeding years of segregation and institutionalized racism in America, endured for one reason — Christian leaders consistently validated it.

From precolonial days, US Christians who defended owning, raping, beating, and selling other humans used biblical interpretations to justify an economic and moral evil that some Christians still won’t acknowledge. They cited passages that seemed to condone slavery, or at least punishment for Black people. The fact that these arguments weren’t from Jesus never seemed to matter, nor did the fact that these arguments were absolute moral sewage.

As they did with the Native peoples, slaveholders and their defenders claimed that converting enslaved Africans to Christianity was actually a benevolent act, since it would obviously save their souls and improve their moral character, as they were gradually worked to death. It was an unholy pretext for maintaining control over enslaved humans and reinforcing their subservience. Being “saved” didn’t save them.

The granddaddy of psychotic theological fraud was “the Curse of Ham,” used for centuries to justify the superiority of some races and the enslavement of nonwhite peoples. I first learned this one when I took an “Old Testament as literature” course in college, and I still have a hard time believing this is something Americans believed.

THE CLAIM: God sanctioned slavery for Black people because of Noah’s son.

THE SCRIPTURE: Genesis 9: 20–27.

The story appears in the Genesis account of Noah, and it is some seriously ridiculous and deeply unholy bullsh**.

Ham was one of Noah’s three sons, all of whom came off the ark post-flood. One day, Noah was happily enjoying the fruits of his vineyard when he got so drunk he passed out naked in his tent. Ham accidentally walked in, and I’ll let Genesis explain the rest:

“Ham, the father of Canaan, saw his father naked and told his two brothers outside. But Shem and Japheth took a garment and laid it across their shoulders; then they walked in backward and covered their father’s naked body. Their faces were turned the other way so that they would not see their father naked. When Noah awoke from his wine and found out what his youngest son had done to him, he said, ‘Cursed be Canaan! The lowest of slaves will he be to his brothers.’”

Now, this curse was directed at Canaan, Ham’s son, and it was prophesied that Canaan’s descendants would be “servants” to the descendants of Shem and Japheth, who didn’t commit the sin of seeing their drunk, naked dad, because Ham had thoughtfully warned them first.

Some might say this story was a sign that Noah needed to go to a meeting, but for centuries of theologians, it meant slavery got to be on the menu. Ham is cited as the father of Canaan, Put, Egypt, and Cush, which sometimes, for some, referred to Africa. Many Christians were duly instructed that

1. Noah cursed Ham;

2. Ham’s brown-skinned descendants went on to populate Africa, and;

3. logically, this meant God wanted African people to always be servants.

You got that? A 500- to 600-year-old man gets so sloshed he passes out buck naked, his kid is forced to witness this, and that’s why slavery’s okay.

It’s so manipulative, so evil, so stupid, and it was more than enough.

THE DEBUNKING: Where to begin?

Noah cursed Canaan, Ham’s son, who wasn’t even there. Why? Some scholars have speculated it’s a storytelling device, as the Canaanites would later be mortal enemies to the Jewish people. Others theorize that young Canaan was actually the one who saw the old man naked. But if Ham’s descendants were meant to be slaves, and Ham was also the “father of Egypt,” then why was Egypt the nation famous for taking slaves?

It probably won’t surprise you to learn that the Bible never mentions the race of Ham or his descendants. The text simply states that Canaan would be a servant to his relatives. There was never any biblical basis for linking this “curse” to any specific race or ethnic group. Nonetheless, for centuries Black people were known as “the sons of Ham,” and the “Curse of Ham” theology gave a green light to white supremacy and Black subordination.

Christian slavery defenders never doubted their piety, knowing their human property was sanctioned by the Almighty. The penalty for the dad who gets drunk and passes out naked in front of the kids, however, remains unrevealed.

Both Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter-day Saint (Mormon) movement, and his famous successor Brigham Young taught that Black people were under the curse of Ham, as well as the curse of Cain. Recall that after Cain kills his brother and God banishes him from the garden, God puts a mark on Cain so that no one can harm him.

The Mormons believed that the “mark of Cain” meant black skin, leading the largest denomination to forbid Black people to enter the Mormon priesthood. In 1978, when Christian president Jimmy Carter threatened to revoke their tax-exempt status over this racism, God suddenly revealed that they were finally allowed to let dark-skinned men — only men — become priests.

The Curse of Ham would eventually be fully debunked by scholars as a misapplication of scripture, but centuries of damage had been done.

We should be very clear — there is no possible way to follow the teachings of Jesus and engage in or defend the practice of slavery. Christians who own slaves aren’t Christian, no matter how brutally they force their slaves to convert.

Jesus lays down the Golden Rule in both Matthew 7:12 and Luke 6:31 when he says, “Do to others as you would have them do to you.” Unless you’re enslaving someone because you yourself would like someone to do it to you, this one’s pretty airtight. Raping, mutilating, and owning people are in no way covered under this policy.

Defending monuments and flags that celebrate white supremacists who slaughtered US troops to keep innocent people enslaved isn’t really covered by Jesus, either.

Once slavery was officially ended, a century of American apartheid began. And it probably won’t surprise you to learn that under Jim Crow, Christians on the right argued that racial segregation was just part of God’s natural order.

Sure, slavery was wrong, and we get that now (even though we put up statues glorifying the guys who fought for it). But segregation, they preached, was a holy and sacred way to preserve the purity of each race, which was seen as a moral duty. They claimed that God created distinct races, and that mingling or mixing them was against His divine plan; the Bible justified separate racial nations with God-ordained boundaries, which proves that God would hate integration.

Four years after the federal desegregation mandates following Brown v. Board of Education, Southern Baptist pastor Rev. Jerry Falwell sermonized, “If Chief Justice [Earl] Warren and his associates had known God’s word and had desired to do the Lord’s will, I am quite confident that the 1954 decision would never have been made… When God has drawn a line of distinction, we should not attempt to cross that line.”

Rev. Bob Jones Sr. gave a radio address on Easter Sunday 1960 entitled “Is Segregation Scriptural?” in which he cited Acts of the Apostles: “From one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands” (Acts 17:26).

This was proof, said Jones, “that God Almighty fixed the bounds of their habitation. That is as clear as anything that was ever said.”

Except “nations” doesn’t mean “races.” Also, the verse clearly focuses on the unity of all humanity as descendants of one ancestor (Adam), highlighting our shared origin. This actually signifies equality and cancels out any claim of racial superiority.

Jesus never condemns interracial or interethnic relationships. His focus is always on the human heart, breaking down barriers, and one’s relationship with God, never external attributes like race or ethnicity. White supremacists don’t read the book.

It was only in 1976 that the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia struck down state laws banning interracial marriage, declaring them unconstitutional. And for decades, nobody ever had to worry that a future Supreme Court might revisit it.

White People, Tired of Taking It from the Man

A core element of Christian nationalism is the myth that America was founded as a deeply Christian nation, and yeah, we may have dabbled in a little ethnic cleansing, some random occasional slavery, and some barely there segregation, but that doesn’t matter in our golden imagined past.

I hope I’m not spoiling anything here, but most Christian racists don’t think their views are problematic. They’ll tell you that white Christians built the US all on their own, and that anyone who uses woke race-baiting terms like “slavery” or “genocide” or “systemic” probably hates white people, and that’s why we need prayer in schools.

For all of our lives — and our parents’ and grandparents’ — white Christians have dominated society and influence in the US. In the 1970s and 1980s, white Christians (including both Protestants and Catholics) made up a majority of the population, accounting for nearly two-thirds of Americans.

But by the early 2020s, this figure had dropped to about 40 percent. White evangelical Protestants, a significant subgroup, have also experienced decline, shrinking to roughly 14 percent of the population as of 2022.

Today, a large segment of the Republican Party base believes whites are the true victims of racism and Christians are under attack. Which makes a lot of sense when you consider that our most popular religion has always been Christianity, whites are still our largest racial group, and white Christians still dominate elected office at all levels, as well as the judiciary, corporate America, land ownership, media control, and Renaissance fairs.

In a 2020 poll from the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), more than seven in ten Fox News Republicans said that there’s a lot of discrimination against Christians, and 58 percent claimed there’s a lot toward white people. Only around one-third say that Black people (36 percent), Hispanic people (34 percent), or Asian people (27 percent) face discrimination like white folks must endure.

In PRRI’s 2023 survey, asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement “immigrants are invading our country and replacing our cultural and ethnic background,” 81 percent of Christian nationalist adherents agreed.

The creeping panic of expecting no longer to be the majority has led some of our friends and neighbors to see Christian nationalism as the only way to get a lost nation back on track. It’s all about power and domination. The movement is growing, and it doesn’t have to be huge to be dangerous. Quite a few of these racists are armed, delusional, and in the process of completely freaking out.

Given the very clear ethical teachings of Jesus, white supremacy must be called out as not only a social evil but also a theological heresy. In her essential White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America, Anthea Butler writes, “Because of racism, evangelical decency was lost, and evangelicals’ resentments grew.”

I asked her, is there even a way to “fix” the movement?

She replied, “Evangelicals will have to become more accepting of others, willing to let go of racism, and actually pay attention to the red-letter words of Jesus. Right now, I don’t think there is any way to fix the movement unless it has a crushing, decisive defeat at its quest to make America a theocracy.”

We’re presently witnessing US white supremacists finally realizing they’re about to become a minority. They’re not going to go gracefully.

According to the US Census Bureau and various studies based on trends in birth rates, immigration, and changing racial and ethnic identification, white folks are projected to become a minority (meaning less than 50 percent of the total population) around the year 2045.

So, if you’re a Christian who’s afraid of one day becoming a minority, this might be a perfect time to be more Christian to minorities.

Let me end where I began, with my grandfather, Lenny the house painter from Brooklyn.

When I was 14, Lenny’s wife died after long, agonizing years of illness; he subsequently came to live with us. He’d been caring for her for years, all the while ignoring his own lung cancer from decades of heavy smoking.

My brothers were both down south that summer and I was doing Long Island regional theater every night. During the day, I’d watch Mets games with my grandfather. As a lifelong Brooklynite who’d never recovered from the Dodgers’ leaving for California, his greatest bigotry was for the Bronx. “I only watch da Mets. Dat’s it. No Yankees. If da Mets aren’t on, I’ll watch da Yankees and root for them ta lose.”

Each night I’d get home late after a rehearsal or show, and my grandfather would be sitting at the kitchen table, in too much discomfort to sleep, smoking. I’d sit with him every single night and talk until I could no longer stay awake; often I’d just sit there with him in silence.

I loved him so much. I was painfully inarticulate and knew he was dying, and I had come to see his many prejudices by then. I couldn’t understand how this particular man had raised a son like my father, who was such a staunch antiracist before that term even existed.

But I do understand, as so many do, how you can love a family member in spite of their racism, antisemitism, xenophobia, homophobia, or misogyny — or in the case of my grandfather, all of the above.

I also understand that sometimes love is the only thing that can draw them away from their prejudices, hang-ups, and hate.

After a few months, my grandfather took a bad fall and was rushed to Stony Brook University Hospital, where it became clear that the end was near. As he lingered, still conscious, my dad called his local parish to request that a priest come perform the last rites. But when the priest arrived, my parents were alarmed that the church had dispatched a Filipino to pray with my grandfather.

The sadness and dread in my parents’ faces was something I’ll never forget. They actually asked me to wait in the hospital corridor at first, as they didn’t want my last memory of the old man to be one of racism, a racism that repels the very love that seeks to heal it.

But in the end, my grandfather was past all that. He warmly received a nonwhite priest. They prayed together and held hands, the last rites were administered, and my grandfather thanked the priest, who embraced him in his hospital bed.

I was holding my grandfather’s hand when he died. But my enduring memory of the whole experience was the gratitude in my parents’ faces. At the end of an old Catholic man’s life, he was able to overcome a curse, a curse that had been placed within him, and embrace someone of a different race with love and gratitude. One of the saddest days of my father’s life was also one of his happiest.

John Fugelsang is a Drama League–nominated actor, comedian, and broadcaster who has hosted many TV shows and podcasts, including the Tell Me Everything series on SiriusXM Progress. This article is adapted from his book Separation of Church and Hate: A Sane Person’s Guide to Taking Back the Bible from Fundamentalists, Fascists, and Flock-Fleecing Frauds.