Read our full issue on the hidden history of the Democrats and Republicans — how the parties formed, flipped, fractured, and became what they are today at thepreamble.com.

Matthew Lyon didn’t glide into Congress the way some men did, carried by polish and pedigree. He arrived like a force –– an Irish immigrant with a face carved by work and weather, eyebrows angled in permanent skepticism, and the unmistakable air of a man who had clawed his way into rooms never meant for him. Nothing about Lyon was built for deference.

At age 15, he boarded a ship bound for the American colonies, willing to subject himself to a long, unpleasant voyage in a ship’s hold, tossed on tempestuous seas and blanketed by the rankness of his fellow beleaguered passengers. Sickness was rampant, food was scarce, and those who survived the voyage arrived thin and exhausted.

Lyon was to become an indentured servant in a printshop run by Ebenezer Watson. Printshops were hot and loud, the smell and the smudges of ink embedded in every surface, but they were also places where ideas circulated as quickly as rumors. For a boy who had left Ireland during a period of steep economic pressure with few prospects, working for Watson offered Lyon something people of his class rarely had: proximity to power. Matthew Lyon learned politics and propaganda at the same wooden cases where he learned to set type.

When the revolution came, he stepped toward it, serving with the Green Mountain Boys under Colonel Seth Warner. Lyon hauled supplies, the New England ice biting his fingers and cheeks, and worked among men like him: all grit, no laudable family tree. When the war ended, Lyon made his way north, to Vermont, surrounded by more people like him, whose lives were hewn by the labor of their own backs. He opened a sawmill, and then a printshop, garnering enough acclaim to be elected to represent Vermont in the House of Representatives.

Matthew Lyon knew that he was never going to be invited to a seat at the table with the genteel tidewater planters. He was no Jefferson, no Madison. If he wanted space, he would have to take it.

In January 1798, Representative Samuel Dana of Connecticut delivered a speech defending the Adams administration’s push to expand the Army. The 106 men of the House of Representatives were seated in a semicircle around Dana and his multiple chins, and Lyon did not approve of Dana’s Federalist ways. Perhaps in an attempt to mock Dana into silence, Lyon began to laugh. Loud enough to halt Dana mid-sentence and rudely enough to catch the attention of another Connecticut man, Roger Griswold.

Griswold rose from his seat, fury rising in his veins, and delivered an insult he knew would sting a self-assured man like Lyon. Mr. Lyon, Griswold charged, had disgraced himself more than once, including being “dismissed with ignominy” for “cowardly behavior” during the Revolutionary War.

To a Congress full of war veterans, the insult was weighty. To call a man a war coward was not simply a jab, it was an affront to his honor.

Lyon wasted no time closing the distance between himself and Griswold. His eyebrows lowered like a cat waiting to pounce, Lyon spat tobacco juice directly at Griswold, the brown stain blooming like old blood.

The chamber erupted; Federalists jumped to their feet and demanded the expulsion of a man such as this one. Democratic-Republicans shouted back, howling that Griswold had no business provoking Lyon with such unproven slurs. The next morning, the newspapers had their headline: THE SPITTING LYON.

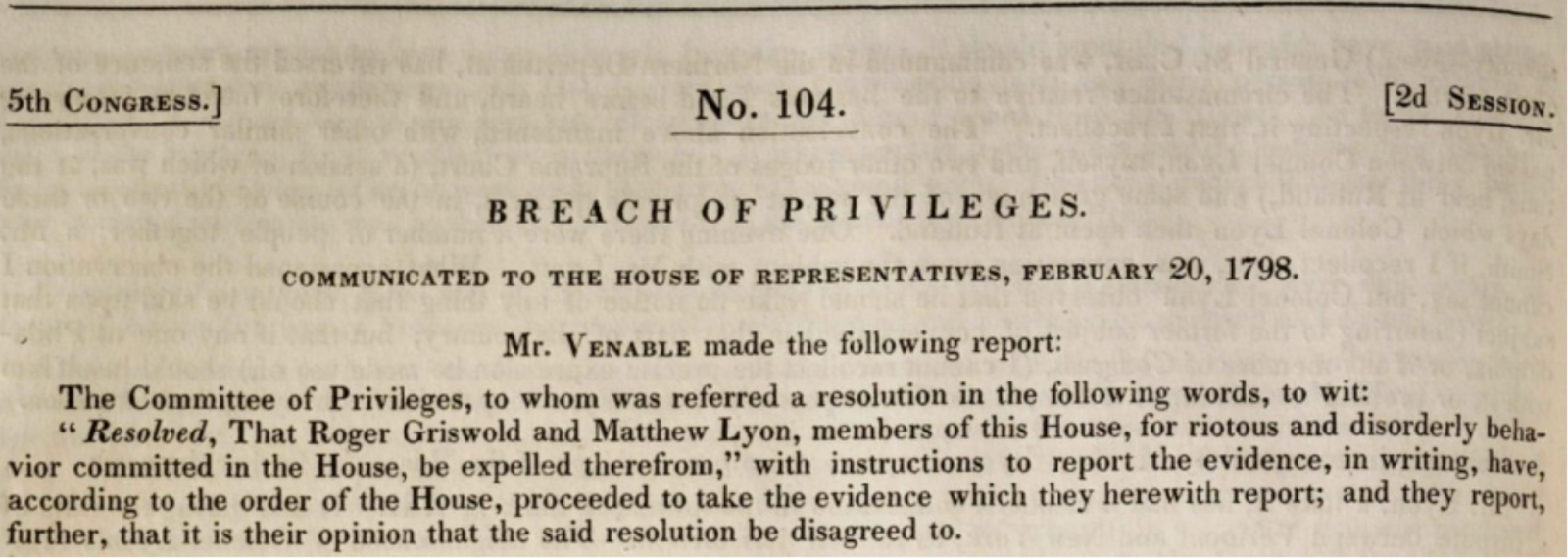

Tempers did not cool when the chambers emptied that night. For the next two weeks, the House of Representatives returned again and again to the same question: Should Matthew Lyon be expelled? The Federalists didn’t have the necessary two-thirds vote, and every failed attempt to whip the votes only sharpened the bitterness between the factions. On February 14, 1798, a final vote was taken. The Federalists had failed to put together a coalition that would banish the big cat from their midst. Griswold was humiliated.

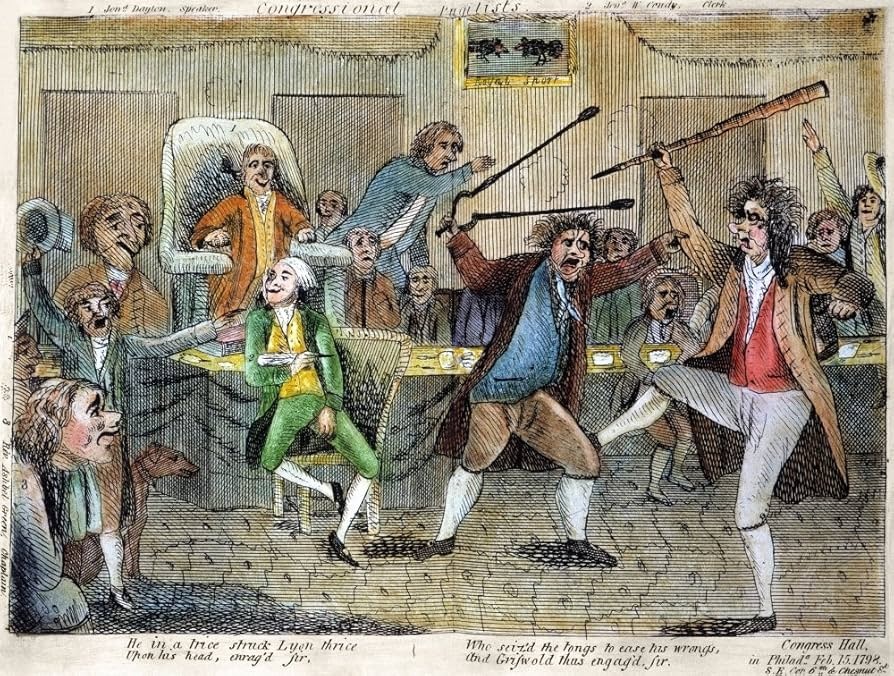

The next morning, having decided to take matters into his own hands, Griswold strode across the House floor carrying a cane and brought the weapon down with a thud on Lyon’s head and shoulders. Hurt and infuriated, Lyon grabbed a set of large fireplace tongs kept beside the chamber hearth and swung back. The men grappled and struck, at first egged on by onlookers, and finally torn apart by colleagues. Newspaper readers the next day woke to lurid descriptions of congressmen trading blows with government-issued tools.

Despite several attempts, neither Griswold nor Lyons was punished. The fight over the fate of the men hardened the plaster between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, solidifying the partisan lines that would shape the fate of the young republic. In the months that followed, Congress passed the Sedition Act, and President John Adams would begin prosecuting his critics.

The Sedition Act made it a federal crime to publish any “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” aimed at bringing the president or Congress “into contempt or disrepute.” Federalists like Adams insisted it protected the nation in a moment of danger, while conflict with Europe knocked, but Democratic-Republicans saw it as a naked attempt to hold a sharpened knife to their throats.

Lyon could not or would not adjust his behavior, publishing an essay in his newspaper accusing President Adams of having an “unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice.” Federal marshals arrested Lyon, and he was put on trial before a Supreme Court justice who rode to Vermont to hear pending cases. Lyon maintained that the Sedition Act violated the First Amendment, but Justice William Paterson told the jurors that Lyon’s intent was what mattered. If his goal was to bring the president into contempt, it was a crime.

For a few brief moments, Lyon hoped the Constitution would prevail. But the jury deliberated quickly, returning a conviction for the spitting Lyon. His punishment? Four months in jail and a $1,000 fine, plus court costs — an amount that would cripple nearly any American of his class.

And yet it was inside that cold, cramped Vermont jail cell that Lyon became more powerful than the Federalists ever expected.

Lyon channeled his anger onto scraps of paper, smuggling essays out through his friends. His supporters distributed his writings across Vermont, and voters began to pick up what Lyon was putting down: if the Adams administration could jail him for criticizing the president, it could jail anyone. When the next round of congressional ballots were counted, Lyon, locked behind a stone wall in Vergennes, had been reelected to his seat in the House of Representatives by a comfortable margin.

The Congress Lyon returned to in early 1799 was no longer divided between two parties that disagreed on the role of federal vs. state governments. Now each party distrusted, resented, and feared what the other might do with its power.

Under the original Constitution, electors did not cast separate votes for president and vice president. Each elector cast two votes for president, and the candidate with the most votes became president while the runner-up became vice president. It was a design drafted in a world without political parties, one where the framers imagined intellectual gentlemen competing for office but not organizing themselves into rival camps. By 1800, that world no longer existed.

The Democratic-Republicans planned for each of their electors to vote for Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, with one elector withholding his second vote from Burr so that Jefferson would finish with one more vote and become the nation’s third president.

But the plan failed. Whether through miscommunication or miscalculation, every Democratic-Republican elector cast one vote for Jefferson and one for Burr, leaving them tied. On the Federalist side, President John Adams was running for reelection with Charles Pinckney, but they received fewer votes out of the gate than either Burr or Jefferson. Adams would not have a second term.

The Constitution was clear: if there was a tie in the Electoral College, the decision of who would become president was kicked to the House of Representatives, where each state’s delegation would cast a single vote.

Ten weeks elapsed before Congress was scheduled to meet again. For ten weeks, the infant nation knew not which course the House would chart. Jefferson or Burr, if you had to choose? Men discussed the question at taverns and in the pews of churches. For many, there was only one option: you could be on the side of the Lord, or you could vote for Thomas Jefferson.

The president of Yale, Timothy Dwight, wrote that if Jefferson were to be elected, the Bible would “be cast into a bonfire,” children, either wheedled or terrified,” would be “united in chanting mockeries against God,” and “our wives and daughters” would become “the victims of legal prostitution.”

Another author summed up the choice plainly: “GOD — AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT or impiously declare for JEFFERSON — AND NO GOD.”

Seventy days after the electors cast their ballots, which resulted in a tie between Jefferson and Burr, the House of Representatives assembled in the new, unfinished Capitol in Washington. Only a portion of the drafty building, still surrounded by scaffolding and stone, was usable. On the morning of February 11, 1801, the clerk opened the certificates of the Electoral College and read aloud the numbers that had hung over the nation for ten anxious weeks. “Thomas Jefferson, 73 votes. Aaron Burr, 73 votes.”

It was now up to the House of Representatives to decide. The cold air from the unfinished walls shivered down the spines of the men who represented the interests of the 16 states. Nine states would be needed to choose a winner. The roll call of the states began:

“New Hampshire: Burr.”

“Massachusetts: Burr.”

“Pennsylvania: Jefferson.”

“New Jersey: Jefferson.”

When the clerk called for Maryland and Vermont, each state voted, “Divided.” The representatives of these states could not arrive at an agreement on whom to cast their ballot for.

Jefferson had won eight states, Burr had taken six, and with two states undecided, there was no winner. “The House has proceeded to a second ballot,” the clerk announced.

And then a third. And then a fourth. Each time, the numbers were the same. As the hours waned, the chamber tightened.

Matthew Lyon and the other representative from Vermont, Lewis Morris, knew that as long as they failed to come to an agreement, their state would be silent in the election. The future hinged on a handful of men in a half-finished room.

The balloting stretched on for seven long days. On the morning of February 17, the House gathered again, the faces of the representatives etched by exhaustion. The clerk began the 36th ballot. Nothing changed. Until the clerk reached Vermont, when the voice of Matthew Lyon said not “Divided” but “Jefferson.” Vermont became the ninth state that Jefferson needed to win the election. (Maryland too finally went for Jefferson, putting him more decisively over the threshold.)

Burr would become Jefferson’s vice president. While holding that office, he would kill Alexander Hamilton in a duel. When his time in Washington expired, he would hatch a treasonous plot against the country. But that is scarcely a story we have time for now.

If anything celebratory passed between the men in that room where it happened, history did not bother to record it. The Annals of Congress captured nothing but the tally — no outburst, no applause, no acknowledgment of the moments that had carried the country there. But the truth sat quietly in the record all the same: when the constitutional machinery jammed and the young republic hovered between two consequential futures, the state that helped break the stalemate spoke through Matthew Lyon.

The indentured servant who became a printer.

The immigrant soldier.

The congressman who spat in a colleague’s face, swung fireplace tongs in self-defense, and wrote “seditious” essays from a stone jail cell.

The Democratic-Republican who favored a fate not tied to the perceived monarchical tendencies of the Federalists and his fellow New Englander, Adams.

He was not the kind of guardian the Framers imagined. But at the exact moment the republic needed one, he was the man who stood in the right place.

On the day it mattered most, Matthew Lyon — unrefined, uninvited, unafraid — helped save the American experiment.

P.S. In one of my favorite games, Alternate American History, imagine what would have happened if Burr had won. It’s likely he would have never shot Hamilton. How might the fate of the republic have been different? I’d love to hear your guesses in the comments.